History of Inuit clothing

With an increase in cultural assimilation and modernization at the beginning of the 20th century, the production of traditional skin garments for everyday use declined as a result of loss of skills combined with shrinking demand.

Since that time, Inuit groups have made significant efforts to preserve traditional skills and reintroduce them to younger generations in a way that is practical for the modern world.

Evidence for the earliest origins of the Inuit clothing system is therefore usually inferred from sewing tools and art objects found at archaeological sites.

[1] In what is now Irkutsk Oblast, Siberia, archaeologists have found carved figurines and statuettes at sites originating from the Mal'ta–Buret' culture which appear to be wearing tailored skin garments, although these interpretations have been contested.

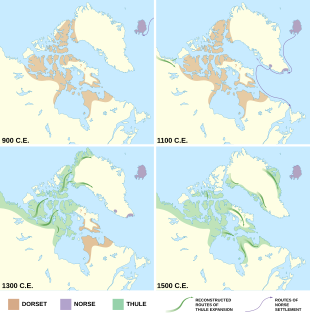

[b][9] Figurines from the Thule culture era of approximately 1000 to 1600 CE found at archaeological sites in Nunavut, Canada also display features consistent with skin clothing.

[10] Thule-era ivory figurines collected in Igloolik in 1939 show the large hoods characteristic of the amauti, as well as the rounded tails of women's parkas.

[11] At Devon Island in Nunavut, Canada, several pieces of frozen skin clothing were found in an archaeological dig conducted in 1985; these items, including an intact child's mitten, have been dated to the early Thule era, around 1000 CE.

[17] Archaeological digs in Utqiaġvik, Alaska from 1981 to 1983 uncovered the earliest known samples of caribou and polar bear skin clothing of the Kakligmiut group of Iñupiat, dated to approximately 1510–1826.

[24][25] Historical records and archaeology indicate that the groups traded as well as fought, and that the Norse did not appear to adopt garments or hunting techniques from the Inuit, who they called skrælings.

[29] After the arrival of Frobisher and his imitators, contact with non-Inuit, especially traders and explorers from America, Europe, and Russia, began to have a greater influence on the construction and appearance of Inuit clothing.

Women's clothing was seen as particularly inappropriate, as the cut of certain garments could expose their trousers or even their bare thighs, so they were often pressured into wearing long skirts or dresses to conceal their legs.

[38] Similarly, in the mid-1800s, Inuit in West Greenland began to sell their pelts rather than making clothes from them, as the newly introduced cash economy made their previous subsistence lifestyle difficult to maintain.

[46] Most Inuit men working on whaling ships across the Arctic adopted cloth garments completely during the summer, generally retaining only their waterproof sealskin kamiit.

[47][32] While Inuit men easily adopted outside clothing, the women's amauti, specifically tailored to its function as a mother's garment, had no European ready-made equivalent.

[44] Beginning in the middle of the 19th-century, the Iñupiaq people of northern Alaska began to use colorful cotton fabrics like drill and calico to make over-parkas to protect their caribou garments from dirt and snow.

[56] Although the Mother Hubbard only arrived there in the late 19th century, it largely eclipsed historical styles of clothing to the point where it is now seen as the traditional women's garment in those areas.

[73] In contrast, Scott promoted his rejection of Inuit furs in favor of traditional British textile-based expedition gear as a point of nationalistic pride.

[75] The production of traditional skin garments for everyday use has declined in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries as a result of loss of skills combined with shrinking demand.

[84][85] The time available for traditional skills was further reduced in areas of significant Christian influence, as Sundays were seen as a day of rest on which to attend church services, not to work.

[91] From the 1960s to the 1980s, strong opposition to seal hunting from the animal rights movement, particularly an influential 1976 Greenpeace Canada campaign, led to significant restrictions on the import of sealskin goods in the United States (1972) and the European Economic Community (1983).

[126][94] As of 2023[update], the Northwest Territories government supports programs to assist artisans in acquiring hide and fur materials and accessing international markets.

[131] Beginning in 2023, a group of Inuit artists and seamstresses called Agguaq began working with museums in order to study ancient garments with an eye to reviving and modernizing the designs.

[54] Although it is uncommon for modern Inuit to wear complete outfits of traditional skin clothing, fur boots, coats and mittens are still popular in many Arctic places.

Skin clothing is preferred for winter wear, especially for Inuit who make their living outdoors in traditional occupations such as hunting and trapping, or modern work like scientific research.

[142][143] Even garments made from woven or synthetic fabric today adhere to ancient forms and styles in a way that makes them simultaneously traditional and contemporary.

"[79] Issenman describes the continued use of traditional fur clothing as not simply a matter of practicality, but "a visual symbol of one's origin as a member of a dynamic and prestigious society whose roots extend into antiquity.

[148][149] In 1999, American designer Donna Karan of DKNY sent representatives to the western Arctic to purchase traditional garments, including amauti, to use as inspiration for an upcoming collection.

[156][164] Melodie Haana-SikSik Lavallée combined satin with sealskin to make items that ranged from "Victorian gowns and bustiers to flapper-inspired dresses and 60s-inspired suits".

[196] The following year, the company released an expanded collection called Atigi 2.0, which involved eighteen seamstresses who produced a total of ninety parkas.

Gavin Thompson, vice-president of corporate citizenship for Canada Goose told CBC that the brand had plans to continue expanding the project in the future.