Inverse kinematics

In computer animation and robotics, inverse kinematics is the mathematical process of calculating the variable joint parameters needed to place the end of a kinematic chain, such as a robot manipulator or animation character's skeleton, in a given position and orientation relative to the start of the chain.

Given joint parameters, the position and orientation of the chain's end, e.g. the hand of the character or robot, can typically be calculated directly using multiple applications of trigonometric formulas, a process known as forward kinematics.

This occurs, for example, where a human actor's filmed movements are to be duplicated by an animated character.

[4] This is important because robot tasks are performed with the end effectors, while control effort applies to the joints.

Inverse kinematics transforms the motion plan into joint actuator trajectories for the robot.

Kinematic analysis allows the designer to obtain information on the position of each component within the mechanical system.

[8][9] Other applications of inverse kinematic algorithms include interactive manipulation, animation control and collision avoidance.

Inverse kinematics is important to game programming and 3D animation, where it is used to connect game characters physically to the world, such as feet landing firmly on top of terrain (see [10] for a comprehensive survey on Inverse Kinematics Techniques in Computer Graphics).

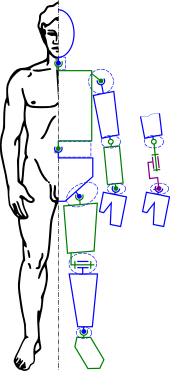

An animated figure is modeled with a skeleton of rigid segments connected with joints, called a kinematic chain.

The inverse kinematics problem computes the joint angles for a desired pose of the figure.

It is often easier for computer-based designers, artists, and animators to define the spatial configuration of an assembly or figure by moving parts, or arms and legs, rather than directly manipulating joint angles.

The assembly is modeled as rigid links connected by joints that are defined as mates, or geometric constraints.

For example, inverse kinematics allows an artist to move the hand of a 3D human model to a desired position and orientation and have an algorithm select the proper angles of the wrist, elbow, and shoulder joints.

Successful implementation of computer animation usually also requires that the figure move within reasonable anthropomorphic limits.

A method of comparing both forward and inverse kinematics for the animation of a character can be defined by the advantages inherent to each.

For instance, blocking animation where large motion arcs are used is often more advantageous in forward kinematics.

However, more delicate animation and positioning of the target end-effector in relation to other models might be easier using inverted kinematics.

Modern digital creation packages (DCC) offer methods to apply both forward and inverse kinematics to models.

If the degrees of freedom of the robot exceeds the degrees of freedom of the end-effector, for example with a 7 DoF robot with 7 revolute joints, then there exist infinitely many solutions to the IK problem, and an analytical solution does not exist.

Further extending this example, it is possible to fix one joint and analytically solve for the other joints, but perhaps a better solution is offered by numerical methods (next section), which can instead optimize a solution given additional preferences (costs in an optimization problem).

An analytic solution to an inverse kinematics problem is a closed-form expression that takes the end-effector pose as input and gives joint positions as output,

One issue with these solvers, is that they are known to not necessarily give locally smooth solutions between two adjacent configurations, which can cause instability if iterative solutions to inverse kinematics are required, such as if the IK is solved inside a high-rate control loop.

Many industrial 6DOF robots feature three rotational joints with intersecting axes ("spherical wrist").

The core idea behind several of these methods is to model the forward kinematics equation using a Taylor series expansion, which can be simpler to invert and solve than the original system.

Taking the Moore–Penrose pseudoinverse of the Jacobian (computable using a singular value decomposition) and re-arranging terms results in where

Applying the inverse Jacobian method once will result in a very rough estimate of the desired

Existing methods based on the Hessian matrix of the system have been reported to converge to desired

These methods perform simple, iterative operations to gradually lead to an approximation of the solution.

The heuristic algorithms have low computational cost (return the final pose very quickly), and usually support joint constraints.

The most popular heuristic algorithms are cyclic coordinate descent (CCD)[15] and forward and backward reaching inverse kinematics (FABRIK).