Inviscid flow

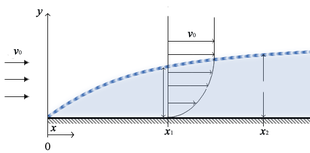

Using the Euler equation, many fluid dynamics problems involving low viscosity are easily solved, however, the assumed negligible viscosity is no longer valid in the region of fluid near a solid boundary (the boundary layer) or, more generally in regions with large velocity gradients which are evidently accompanied by viscous forces.

His hypothesis establishes that for fluids of low viscosity, shear forces due to viscosity are evident only in thin regions at the boundary of the fluid, adjacent to solid surfaces.

[5] Real fluids experience separation of the boundary layer and resulting turbulent wakes but these phenomena cannot be modelled using inviscid flow.

Separation of the boundary layer usually occurs where the pressure gradient reverses from favorable to adverse so it is inaccurate to use inviscid flow to estimate the flow of a real fluid in regions of unfavorable pressure gradient.

[5] The Reynolds number (Re) is a dimensionless quantity that is commonly used in fluid dynamics and engineering.

[6][7] Originally described by George Gabriel Stokes in 1850, it became popularized by Osborne Reynolds after whom the concept was named by Arnold Sommerfeld in 1908.

[6] In inviscid flow, since the viscous forces are zero, the Reynolds number approaches infinity.

[1] In such cases (Re>>1), assuming inviscid flow can be useful in simplifying many fluid dynamics problems.

In a 1757 publication, Leonhard Euler described a set of equations governing inviscid flow:[10]

When the fluid is inviscid, or the viscosity can be assumed to be negligible, the Navier-Stokes equation simplifies to the Euler equation:[1] This simplification is much easier to solve, and can apply to many types of flow in which viscosity is negligible.

It is important to note, that negligible viscosity can no longer be assumed near solid boundaries, such as the case of the airplane wing.

[1] In turbulent flow regimes (Re >> 1), viscosity can typically be neglected, however this is only valid at distances far from solid interfaces.

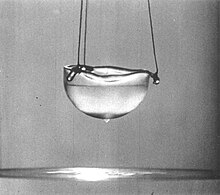

[13] At temperatures above the lambda point, helium exists as a liquid exhibiting normal fluid dynamic behavior.

[14] In addition, the thermal conductivity is very large, contributing to the excellent coolant properties of superfluid helium.

[16] Superfluid helium has a very high thermal conductivity, which makes it very useful for cooling superconductors.

Superconductors such as the ones used at the LHC (Large Hadron Collider) are cooled to temperatures of approximately 1.9 Kelvin.

Using lasers to look at small droplets allows scientists to view behaviors that may not normally be viewable.

The upper diagram shows zero circulation and zero lift. It implies high-speed vortex flow at the trailing edge which is known to be inaccurate in a model of the steady state.

The lower diagram shows the Kutta condition which implies finite circulation, finite lift, and no vortex flow at the trailing edge. These characteristics are known to be accurate as models of the steady state in a real fluid.