Boundary layer

A breeze disrupts the boundary layer, and hair and clothing protect it, making the human feel cooler or warmer.

When a fluid rotates and viscous forces are balanced by the Coriolis effect (rather than convective inertia), an Ekman layer forms.

The viscous nature of airflow reduces the local velocities on a surface and is responsible for skin friction.

As the flow continues back from the leading edge, the laminar boundary layer increases in thickness.

The aerodynamic boundary layer was first hypothesized by Ludwig Prandtl in a paper presented on August 12, 1904, at the third International Congress of Mathematicians in Heidelberg, Germany.

This allows a closed-form solution for the flow in both areas by making significant simplifications of the full Navier–Stokes equations.

For the case where there is a temperature difference between the surface and the bulk fluid, it is found that the majority of the heat transfer to and from a body takes place in the vicinity of the velocity boundary layer.

In high-performance designs, such as gliders and commercial aircraft, much attention is paid to controlling the behavior of the boundary layer to minimize drag.

At high Reynolds numbers, typical of full-sized aircraft, it is desirable to have a laminar boundary layer.

This results in a lower skin friction due to the characteristic velocity profile of laminar flow.

This can reduce drag, but is usually impractical due to its mechanical complexity and the power required to move the air and dispose of it.

At lower Reynolds numbers, such as those seen with model aircraft, it is relatively easy to maintain laminar flow.

However, the same velocity profile which gives the laminar boundary layer its low skin friction also causes it to be badly affected by adverse pressure gradients.

As the pressure begins to recover over the rear part of the wing chord, a laminar boundary layer will tend to separate from the surface.

The fuller velocity profile of the turbulent boundary layer allows it to sustain the adverse pressure gradient without separating.

Special wing sections have also been designed which tailor the pressure recovery so laminar separation is reduced or even eliminated.

This represents an optimum compromise between the pressure drag from flow separation and skin friction from induced turbulence.

Using an order of magnitude analysis, the well-known governing Navier–Stokes equations of viscous fluid flow can be greatly simplified within the boundary layer.

Therefore, the equation of motion simplifies to become These approximations are used in a variety of practical flow problems of scientific and engineering interest.

This simplified equation is a parabolic PDE and can be solved using a similarity solution often referred to as the Blasius boundary layer.

[13] For steady two-dimensional compressible boundary layer, Luigi Crocco[14] introduced a transformation which takes

Unlike the laminar boundary layer equations, the presence of two regimes governed by different sets of flow scales (i.e. the inner and outer scaling) has made finding a universal similarity solution for the turbulent boundary layer difficult and controversial.

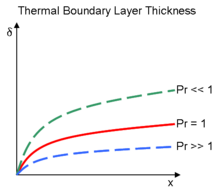

Similar approaches to the above analysis has also been applied for thermal boundary layers, using the energy equation in compressible flows.

The lack of accuracy and generality of such models is a major obstacle in the successful prediction of turbulent flow properties in modern fluid dynamics.

In 1928, the French engineer André Lévêque observed that convective heat transfer in a flowing fluid is affected only by the velocity values very close to the surface.

[22] Analytic solutions can be derived with the time-dependent self-similar Ansatz for the incompressible boundary layer equations including heat conduction.

[24] Despite being frequently assumed to be inherently turbulent, this accidental observation demonstrates that natural wind behaves in practice very close to an ideal fluid, at least in an observation resembling the expected behaviour in a flat plate, potentially reducing the difficulty in analysing this kind of phenomenon on a larger scale.

Paul Richard Heinrich Blasius derived an exact solution to the above laminar boundary layer equations.

It is used in concepts like the Aurora D8 or the French research agency Onera's Nova, saving 5% in cruise by ingesting 40% of the fuselage boundary layer.

Propulsive efficiencies are up to 90% like counter-rotating open rotors with smaller, lighter, less complex and noisy engines.