Intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cell

They have at least three primary functions: Photoreceptive ganglion cells have been isolated in humans, where, in addition to regulating the circadian rhythm, they have been shown to mediate a degree of light recognition in rodless, coneless subjects suffering with disorders of rod and cone photoreceptors.

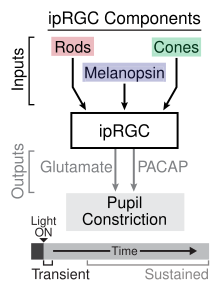

The photopigment of photoreceptive ganglion cells, melanopsin, is excited by light mainly in the blue portion of the visible spectrum (absorption peaks at ~480 nanometers[10]).

The axons from these ganglia innervate regions of the brain related to object recognition, including the superior colliculus and dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus.

ipRGCs release both pituitary adenylyl cyclase-activating protein (PACAP) and glutamate onto the SCN via a monosynaptic connection called the retinohypothalamic tract (RHT).

[16] Other post synaptic targets of ipRGCs include: the intergenticulate leaflet (IGL), a cluster of neurons located in the thalamus, which play a role in circadian entrainment; the olivary pretectal nucleus (OPN), a cluster of neurons in the midbrain that controls the pupillary light reflex; the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (VLPO), located in the hypothalamus and is a control center for sleep; as well as to[clarify] the amygdala.

Zaidi and colleagues showed that in humans the retinal ganglion cell photoreceptor contributes to conscious sight as well as to non-image-forming functions like circadian rhythms, behaviour and pupillary reactions.

Zaidi and colleagues' work with rodless, coneless human subjects hence has also opened the door into image-forming (visual) roles for the ganglion cell photoreceptor.

Tests conducted by Jennifer Ecker et al. found that rats lacking rods and cones were able to learn to swim toward sequences of vertical bars rather than an equally luminescent gray screen.

In work by Zaidi, Lockley and co-authors using a rodless, coneless human, it was found that a very intense 481 nm stimulus led to some conscious light perception, meaning that some rudimentary vision was realized.

[3] Research continued in 1991, when Russell G. Foster and colleagues, including Ignacio Provencio, showed that rods and cones were not necessary for photoentrainment, the visual drive of the circadian rhythm, nor for the regulation of melatonin secretion from the pineal gland, via rod- and cone-knockout mice.

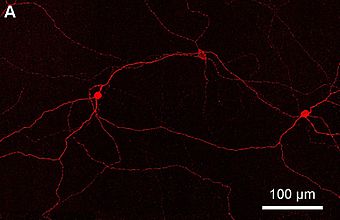

[21] The photoreceptors were identified in 2002 by Samer Hattar, David Berson and colleagues, where they were shown to be melanopsin expressing ganglion cells that possessed an intrinsic light response and projected to a number of brain areas involved in non-image-forming vision.

[24][25] Dennis Dacey and colleagues showed in a species of Old World monkey that giant ganglion cells expressing melanopsin projected to the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN).

In 2007, Zaidi and colleagues published their work on rodless, coneless humans, showing that these people retain normal responses to nonvisual effects of light.

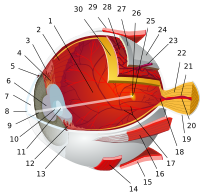

[9][27] The identity of the non-rod, non-cone photoreceptor in humans was found to be a ganglion cell in the inner retina as shown previously in rodless, coneless models in some other mammals.