Iraqi art

[1] In the 20th century, an art revival, which combined both tradition and modern techniques, produced many notable poets, painters and sculptors who contributed to the inventory of public artworks, especially in Baghdad.

[4] Although British archaeologists excavated a number of Iraqi sites, including Nimrud, Nineveh and Tell Halaf in Iraq in the 19th century,[5] they sent many of the artefacts and statues to museums around the world.

It was not until the early 20th century, when a small group of Iraqi artists were awarded scholarships to study abroad, that they became aware of ancient Sumerian art by visiting prestigious museums such as the Louvre, enabling them to reconnect with their cultural and intellectual heritage.

[9] During the early Islamic period, writing was transformed into an "iconophoric message...a carrier of meaning independent of its form [and] into a subject worthy of the most elaborate ornamentation.

Now known as the Baghdad School, this movement of Islamic art was characterised by representations of everyday life and the use of highly expressive faces rather than the stereotypical characters that had been used in the past.

His most well-known works include the illustrations for the book of the Maqamat (Assemblies) in 1237, a series of anecdotes of social satire written by al-Hariri.

[15] Other examples of works in the style of the Baghdad School include the illustrations in Rasa'il al-Ikhwan al-Safa (The Epistles of the Sincere Brethren), (1287); an Arabic translation of Pedanius Dioscorides’ medical text, De Materia Medica (1224)[13] and the illustrated Kalila wa Dimna (Fables of Bidpai), (1222); a collection of fables by the Hindu, Bidpai translated into Arabic.

The Iraqi poet Fuzûlî wrote in Arabic, Persian and Turkish during this time, and continued writing poetry after Ottoman rule was established in 1534.

Traditional art, which included metal-work, rug-making and weaving, glass-blowing, ceramic tiles, calligraphy and wall murals were widely practised during the 19th century.

[19] In the late 19th century, the rise of nationalistic and intellectual movements across the Arab world led to calls for an Arab-Islamic cultural revival.

[22] At the turn of the 20th century, a small group of Iraqis were sent to Istanbul for military training, where painting and drawing was included as part of the curriculum.

[34] Iraq was relatively slow to adopt photography as an industry and art form, due to the religious and social prohibitions on making figurative images.

These activities exposed local Iraqis to the technology, and provided young men with employment opportunities as photographers and camera-men assisting archaeological teams.

Important 20th-century Iraqi photographers include: Amri Salim, Hazem Bak, Murad Daghistani, Covadis Makarian, Sami Nasrawi, Ahmed Al-Qabbani, Jassem Al-Zubaidi, Fouad Shaker and Rashad Ghazi amongst others.

The artist, Jananne al-Ani has explored the dichotomy of Orient/ Occident in her work, and has also used photography to question the wearing of the veil while Halim Alkarim uses blurred images to suggest the political instability of Iraq.

The period was characterised by original designs produced by local architects, who had been trained in Europe, including: Mohamed Makiya, Makkiyya al-Jadiri, Mazlum, Qatan Adani and Rifat Chadirji.

[45] He explains: "From the very outset of my practice, I thought it imperative that, sooner or later, Iraq create for itself an architecture regional in character yet simultaneously modern, part of the current international avant-garde style.

[49] The mudhif (or reed dwelling) or the bayt (houses) with features such as the shanashol (the distinctive oriel window with timber lattice-work) and bad girs (wind-catchers) were being lost with alarming haste.

Following World War One, a group of Polish officers, who had been part of the Foreign Legion,[54] arrived in Baghdad and introduced local artists to a European style of painting, which in turn fostered a public appreciation of art.

In early 1959, Qasim commissioned Jawad Saleem to create Nasb al-Hurriyah (Monument to Freedom,) to commemorate Iraq's independence.

[58] In the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s, the Ba'ath Party mounted a program to beautify the city of Baghdad which led to numerous public art works being commissioned.

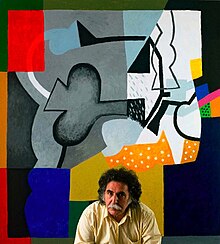

[61] A notable feature of the Iraqi visual arts scene lies in artists' desires to link tradition and modernity in artworks.

The Iraqi artist, Madiha Omar, who was active from the mid-1940s, was one of the pioneers of the hurufiyya movement, since she was the first to explore the use of Arabic script in a contemporary art context and exhibited hurufiyya-inspired works in Washington as early as 1949.

[66] These groups include: "We believe that heritage is not a prison, a static phenomenon or a force capable of repressing creativity so long as we have the freedom to accept or challenge its norms... We are the new generation.

Iraq has produced a number of world-class painters and sculptors including Ismail Fatah Al Turk (1934–2008), Khalid Al-Jadir (1924–1990), and Mohammed Ghani Hikmat.

[108] A committee, headed by the respected artist and sculptor, Mohammed Ghani Hikmat, was formed with the objective of recovering stolen artworks and proved somewhat more effective.

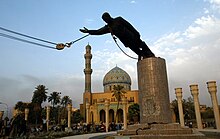

[110] Since 2003, attempts at de-Ba'athification have been evident, with the announcement of plans to rid Baghdad's cityscape of monuments constructed during Saddam Hussein's rule.

However, due to public pressure, plans have been made to store such monuments rather than arrange for their total destruction as had occurred in previous regimes.

[118] In 2014, Islamic militants invaded the city of Mosul, destroying ancient monuments and statues, which they perceived to be blasphemous, and ransacked the History Museum.

He also started to paint "martyr posters" that depict the soldiers and police officers who have died during the military operations to liberate Nineveh.