Assyria

[10] The triumph of ancient Assyria can be attributed not only to its vigorous warrior-monarchs but also to its adeptness in efficiently assimilating and governing conquered territories using inventive and advanced administrative mechanisms.

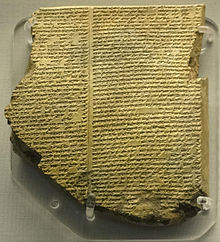

[7] Ancient Assyria also left a legacy of great cultural significance,[11] particularly through the Neo-Assyrian Empire, making a prominent impression in later Assyrian, Greco-Roman, and Hebrew literary and religious tradition.

From the time of its rise as a territorial state in the 14th century BC and onward, Assyria was referred to in official documents as māt Aššur ("land of Ashur"), marking its shift to being a regional polity.

The Greeks called the Levant "Syria" and Mesopotamia "Assyria", even though the local population, both at that time and well into the later Christian period, used both terms interchangeably to refer to the entire region.

And because, in sources predating the Greek ones, the shortened form "Syria" is attested as a synonym for Assyria, notably in Luwian and Aramaic texts from the time of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, modern scholars overwhelmingly support the conclusion that the names are connected.

[27] Though the sites of some nearby cities that would later be incorporated into the Assyrian heartland, such as Nineveh, are known to have been inhabited since the Neolithic,[28] the earliest archaeological evidence from Assur dates to the Early Dynastic Period, c. 2600 BC.

[43] After Shamshi-Adad's death, the political situation in northern Mesopotamia was highly volatile, with Assur at times coming under the brief control of Eshnunna,[44] Elam[45][46] and the Old Babylonian Empire.

[45][46] At some point, the city returned to being an independent city-state,[47] though the politics of Assur itself were volatile as well, with fighting between members of Shamshi-Adad's dynasty, native Assyrians and Hurrians for control.

An invasion by the Hittite king Mursili I in c. 1595 BC destroyed the dominant Old Babylonian Empire, allowing the smaller kingdoms of Mitanni and Kassite Babylonia to rise in the north and south, respectively.

[54] Assyria's rise was intertwined with the decline and fall of the Mitanni kingdom, its former suzerain, which allowed the early Middle Assyrian kings to expand and consolidate territories in northern Mesopotamia.

Under Ashur-dan II (r. 934–912 BC), who campaigned in the northeast and northwest, Assyrian decline was at last reversed, paving the way for grander efforts under his successors.

[73] This time of stagnation came to an end with the rise of Tiglath-Pileser III (r. 745–727 BC), who reduced the power of the magnates,[74] consolidated and centralized the holdings of the empire,[9][75] and through his military campaigns and conquests more than doubled the extent of Assyrian territory.

One of the primary reasons was the inability of the Neo-Assyrian kings to resolve the "Babylonian problem"; despite many attempts to appease Babylonia in the south, revolts were frequent all throughout the Sargonid period.

[91] Under the Seleucid Empire, which controlled Mesopotamia from the late 4th to mid-2nd century BC, Assyrian sites such as Assur, Nimrud and Nineveh were resettled and a large number of villages were rebuilt and expanded.

From the time of Ashur-resh-ishi I onward, the religious and cultic duties of the king were pushed somewhat into the background, though they were still prominently mentioned in accounts of building and restoring temples.

[145] Every province was headed by a provincial governor (bel pāḫete,[144] bēl pīhāti[146] or šaknu)[146] who was responsible for handling local order, public safety and economy.

[153] Per estimates by Karen Radner, an official message sent in the Neo-Assyrian period from the western border province Quwê to the Assyrian heartland, a distance of 700 kilometers (430 miles) over a stretch of lands featuring many rivers without any bridges, could take less than five days to arrive.

[156] Some professional (though not standing) troops are also attested in the Middle Assyrian period, dubbed ḫurādu or ṣābū ḫurādātu, though what their role was is not clear due to the scarcity of sources.

[162] Old Assyrian society was divided into two main groups: slaves (subrum) and free citizens, referred to as awīlum ("men") or DUMU Aššur ("sons of Ashur").

[164] Other lower classes of the Middle Assyrian period included the ālāyû ("village residents"), ālik ilke (people recruited through the ilku system) and the hupšu, though what these designations meant in terms of social standing and living standards is not known.

Because many individuals designated as wardum in Assyrian texts are described as handling property and carrying out administrative tasks on behalf of their masters, many may have in actuality been free servants and not slaves in the common meaning of the term.

[184] As can be gathered from hiring contracts and other records, the trade involved people of many different occupations, including porters, guides, donkey drivers, agents, traders, bakers and bankers.

One of the inscriptions that attest to this view, as well as royal Assyrian policies enacted to encourage assimilation and cultural mixture, is Sargon II's account of the construction of Dur-Sharrukin.

[202] Though many foreign states ruled over Assyria in the millennia following the empire's fall, there is no evidence of any large scale influx of immigrants that replaced the original population,[188] which instead continued to make up a significant portion of the region's people until the Mongol and Timurid massacres in the late 14th century.

[205] The self-designation suryāyā, suryāyē or sūrōyē,[193] sometimes translated as "Syrian",[205] is believed to be derived from the Akkadian term assūrāyu ("Assyrian"), which was sometimes even in ancient times rendered in the shorter form sūrāyu.

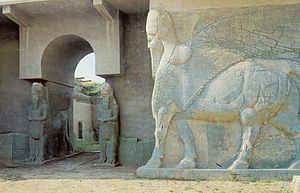

Some examples of features of ancient Assyrian architecture include stepped merlons,[232] vaulted roofs,[233] and palaces to a large degree often being made up of sets of self-contained suites.

[241] In the Middle Assyrian period, from Ashur-uballit I onward, seals looked quite different and appear to emphasize royal power, rather than the theological and cosmic sources of the king's right to rule.

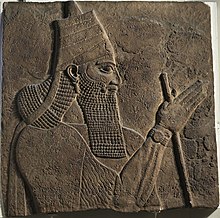

[245] In terms of Neo-Assyrian artwork, modern scholars have paid particular attention to the reliefs produced under Ashurbanipal, which have been described as possessing a distinct "epic quality" unlike the art under his predecessors.

In the Middle Assyrian period, Ashur is attested with the title "king of the gods", a role previous civilizations in both northern and southern Mesopotamia ascribed to Enlil.

Records from temples showcase that divination in the form of astrology and extispicy (studying the entrails of dead animals) were important parts of the Assyrian religion since they were believed to be means through which deities communicated with the mortal world.