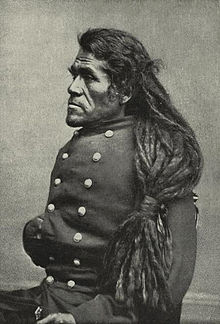

Irataba

Noted for his large physical size and gentle demeanor, he later helped and protected other expeditions, earning him a reputation among whites as the most important native leader in the region.

[16] In contemporary accounts Irataba was described as an eloquent speaker, and linguist Leanne Hinton suggests that he was among the first Mohave people to become fluent in English, which he learned through his many interactions with Anglo-Americans.

Most historical sources for the life of Irataba come from descriptions by white explorers or government agents with whom he interacted, or from contemporary newspapers that reported on his visits to the East Coast and California, and on the conflicts in Arizona territory.

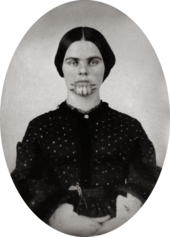

[5] On March 19, 1851, a family of Brewsterite settlers, the Oatmans, who were traveling by wagon train in what is now Arizona, were attacked by a band of Western Yavapai, probably the Tolkepaya.

On February 23, 1854, Irataba, Cairook, and other Mohave people encountered an expedition led by military officers Amiel Whipple and J.C. Ives, as the group approached the Colorado en route to California.

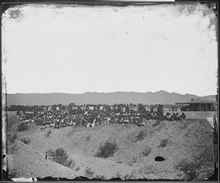

[25][b] Whipple and his men counted six hundred Mohave gathered near their camp, trading corn, beans, squash (plant), and wheat for beads and calico.

[35] Möllhausen again accompanied the expedition, and was impressed with the Mohave guides, later noting Irataba's enthusiastic handshake and lamenting that their only form of communication was sign language.

He also noted that Irataba and the Mohave readily began wearing European clothes given to them by members of the expedition, and showed great interest in smoking tobacco.

[37][38][c] Irataba guided the party into the Mohave Canyon, indicating the location of rapids and advising the Explorer's pilot of convenient places to anchor while camping for the night.

[40] When they reached the entrance to the Black Canyon of the Colorado, the ship crashed against a submerged rock, throwing several men overboard, dislodging the boiler, and damaging the wheelhouse.

[41] The expedition had relied on beans and corn provided by the Mohave during the previous weeks; as their supplies dwindled they grew increasingly anxious about the arrival of a resupply pack train from Fort Yuma.

[42] When Irataba returned he informed Ives that he would not venture any deeper into the territory of the Hualapais, but agreed to help them locate friendly guides in the region before parting company.

[45] On April 4, the Mohave received payment for their services; Möllhausen described the exchange: "Lieutenant Ives informed Irataba that he had been authorized by the 'Great Grandfather in Washington' to give him two mules ... for his loyalty and his trustworthiness so that he could take his possessions and those of his companions more conveniently to his home valley.

"[46] Following their experiences with the Sitgreaves and Whipple expeditions, and encounters with Mormons and the soldiers at Fort Yuma, the Mohave were aware that whites were immigrating to the region in increasing numbers.

[48][38] In October 1857, an expedition led by Edward Fitzgerald Beale was tasked with establishing a trade route along the 35th parallel from Fort Smith, Arkansas, to Los Angeles, California.

[50][57] The incident was widely publicized in the media and labeled "a massacre",[58] scaring many white Californians who feared being cut off from the eastern US by hostile natives, and it motivated the War Department to quickly subjugate the tribe.

"[60] Irataba, weary of the constant fighting and worried that further conflicts with neighboring tribes would draw more attention from the US soldiers, organized a peace expedition to the Maricopa, settling the ancient disputes between the two peoples.

This attack prompted an assault on Armistead's detachment, who from an advantageous position on the high ground were able to repel the Mohave, killing many of them in a battle that lasted most of the day.

[83] Earlier, concern for protecting incoming miners brought together tribal leaders to Ft. Yuma in April 1863, including Irataba, where they pledged to allow prospectors into their country.

[97] Irataba moved on to Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., where he earned great acclaim; government officials and military officers lavished him with gifts of medals, swords, and photographs.

In 1863, Charles Debrille Poston, the first Superintendent of Indian Affairs of the Arizona Territory, called a conference between the Chemehuevi and Irataba's faction of the Mohave, in which he convinced them to form an alliance with the US against the Apache.

I have full confidence in the friendship of Iratabu towards white men, but not in his tribe, if troubles with any other Indians should occur, while he has more influence over them than any other chief, his control over them is not complete, and they are as likely to lead him (as he is them).

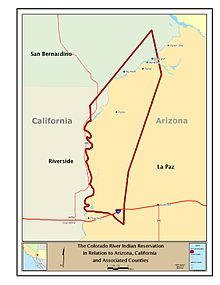

[107]Faced with Irataba's disagreement, Poston promised that the US government would assist the Mohave with installing an irrigation system at the Colorado that would make most of the reservation arable.

[109] General James Henry Carleton thought a reservation was unnecessary, and engineer Herman Ehrenberg disagreed with Poston's proposed location on the basis that the soil was too alkaline for farming, the need for irrigation too great, and the task of raising the river too insurmountable.

[111] Ehrenberg's concerns proved valid, and neither Poston nor any subsequent US authority was willing to dedicate the considerable resources required to make the location suitable for farming.

[121] According to a contemporary news report based on second hand accounts from white travelers, the captors feared that killing him would invite repercussions from the soldiers stationed at Fort Mohave, so they instead stripped him naked and sent him home badly beaten.

In 1871–72, General George Crook came to the Mohave reservation looking for a group of Yavapai thought to be responsible for the Wickenburg Massacre, and Irataba had no choice but to turn the war party over to the army.

[123] He traveled to the trial proceedings at Fort Date Creek, where he was instructed to hand tobacco to the Yavapai he believed to be responsible, as a way for him to testify against them without their realizing it.

[137] In 2002, the US Bureau of Land Management designated 32,745 acres (13,251 ha) of the Eldorado Mountains, contained largely within the Lake Mead National Recreation Area, as Ireteba Peaks Wilderness.

[138] In March 2015, the Colorado River Indian Tribes celebrated the sesquicentennial history of their reservation with a weekend-long event that included cultural activities and a parade.