Utah War

[12] The confrontation between the Mormon militia, called the Nauvoo Legion, and the U.S. Army involved some destruction of property and a few brief skirmishes in what is today southwestern Wyoming, but no battles occurred between the contending military forces.

At the height of the tensions, on September 11, 1857, at least 120 California-bound settlers from Arkansas, Missouri and other states, including unarmed men, women, and children, were killed in remote southwestern Utah by a group of local Mormon militia.

[18][19] Taking all incidents into account, William MacKinnon estimated that approximately 150 people died as a direct result of the year-long Utah War, including the 120 migrants killed at Mountain Meadows.

Mormon pioneers began leaving the United States for Utah after a series of severe conflicts with neighboring communities in Missouri and Illinois resulted, in 1844, in the death of Joseph Smith, founder of the Latter Day Saint movement.

Such leading Democrats as Stephen A. Douglas, formerly an ally of the Latter-day Saints began to denounce Mormonism in order to save the concept of popular sovereignty for issues related to slavery.

In addition to popular election, many early LDS Church leaders received quasi-political administrative appointments at both the territorial and federal level that coincided with their ecclesiastical roles, including the powerful probate judges.

[a] These factors contributed to the popular belief that Mormons "were oppressed by a religious tyranny and kept in submission only by some terroristic arm of the Church ... [However] no Danite band could have restrained the flight of freedom-loving men from a Territory possessed of many exits; yet a flood of emigrants poured into Utah each year, with only a trickle ... ebbing back.

Historian Norman Furniss writes that although some of these appointees were basically honest and well-meaning, many were highly prejudiced against the Mormons even before they arrived in the territory and woefully unqualified for their positions, while a few were down-right reprobates.

[31] In addition, the Saints sincerely declared their loyalty to the United States and celebrated the Fourth of July every year with unabashed patriotism, but they were undisguisedly critical of the federal government, which they felt had driven them out from their homes in the east.

Mormon colonists in small outlying communities in the Carson Valley and San Bernardino, California were ordered to leave their homes to consolidate with the main body of Latter-day Saints in Northern and Central Utah.

Thus, in mid-August, militia Colonel Robert T. Burton and a reconnaissance unit were sent east from Salt Lake City with orders to observe the oncoming American regiments and protect LDS emigrants traveling on the Mormon trail.

On July 18, 1857, U.S. Army Captain Stewart Van Vliet, an assistant quartermaster, and a small escort were ordered to proceed directly from Kansas to Salt Lake City, ahead of the main body of troops.

"[56] On September 15, the day after Van Vliet left Salt Lake City, Young publicly declared martial law in Utah with a document almost identical to that printed in early August.

Dealing with a heavy snowfall and intense cold, the Mormon men built fortifications, dug rifle pits and dammed streams and rivers in preparation for a possible battle either that fall or the following spring.

[60] Colonel Alexander, whose troops referred to him as "old granny",[61] opted not to enter Utah through Echo Canyon following Van Vliet's report, as well as news of the Mormon fortifications by Taylor and Stowell.

Johnston was soon joined by the 2nd Dragoons commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Philip St. George Cooke, who had accompanied Alfred Cumming, Utah's new governor, and a roster of other federal officials from Fort Leavenworth.

In early November, Joseph Taylor of the Nauvoo Legion escaped captivity at Camp Scott and returned to Salt Lake City to report conditions of the army to Brigham Young.

On November 26, 1857, Brigham Young wrote letter to Colonel Johnston at Fort Bridger inquiring of the prisoners and stating of William "....if you imagine that keeping, mistreating or killing Mr. Stowell will resound to your advantage, future experience may add to the stock of your better judgment.

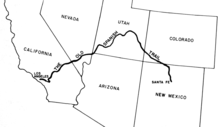

While steaming upstream in the Explorer from the Colorado River Delta toward Fort Yuma in early January 1858, Ives received two hastily written dispatches from his commanding officer informing him of the outbreak of the Mormon War.

[66] Meanwhile, George Alonzo Johnson, a merchant who had an established business transporting goods by steamship between the Colorado River Delta and Fort Yuma, was upset that he had not been awarded command of the expedition's original exploratory mission.

Jacob Hamblin, famed Mormon missionary of the Southwest, whose activities including establishing and maintaining Mormon-Indian alliances along the Colorado, set out in March with three other companions from Las Vegas to learn more about Ives's intentions.

In Buchanan's State of the Union address earlier in the month, he had taken a hard stand against the Mormon rebellion, and had actually asked Congress to enlarge the size of the regular army to deal with the crisis.

[49] However, in his conversation with Kane, Buchanan worried that the Mormons might destroy Johnston's Army at severe political cost to himself, and stated that he would pardon the Latter-day Saints for their actions if they would submit to government authority.

At the end of May, Major Benjamin McCulloch of Texas and Kentucky senator-elect Lazarus W. Powell arrived at Camp Scott as peace commissioners with a proclamation of general pardon from President Buchanan for previous indictments handed down to Mormon leaders.

In Utah, the Nauvoo Legion was bolstered as Mormon communities were asked to supply and equip an additional thousand volunteers to be placed in the over one hundred miles of mountains that separated Camp Scott and Great Salt Lake City.

[18] Consequently, at the end of March 1858, settlers in the northern counties of Utah including Salt Lake City boarded up their homes and farms and began to move south, leaving small groups of men and boys behind to burn the settlements if necessary.

I have no faith in their ability to conduct it; and I believe that before a year has passed over it will be evident to every citizen of the country that they have committed a great blunder ...[74]Therefore in April, the President sent an official peace commission to Utah consisting of Benjamin McCulloch and Lazarus Powell, which arrived in June.

They also hinted that once the new governor was installed and the laws yielded to, "a necessity will no longer exist to retain any portion of the army in the Territory, except what may be required to keep the Indians in check and to secure the passage of emigrants to California.

Arthur P. Welchman, a member of a company of missionaries that was recalled due to the war, wrote of the document:[77] June – On the head-waters of the Sweet-Water, met Grosebecks' camp going to Platt Bridge for a train of goods.

It was so full of lies, and showed so much meanness, that it elicited three groans from the company.On June 19, a newly arrived reporter for the New York Herald somewhat inaccurately wrote, "Thus was peace made – thus was ended the 'Mormon war', which ... may be thus historicized: – Killed, none; wounded, none; fooled, everybody.