Chromatophore

While most chromatophores contain pigments that absorb specific wavelengths of light, the color of leucophores and iridophores is produced by their respective scattering and optical interference properties.

[1] Cephalopods, such as the octopus, have complex chromatophore organs controlled by muscles to achieve this, whereas vertebrates such as chameleons generate a similar effect by cell signalling.

[3] Charles Darwin described the colour-changing abilities of the cuttlefish in The Voyage of the Beagle (1860):[4] These animals also escape detection by a very extraordinary, chameleon-like power of changing their colour.

The colour, examined more carefully, was a French grey, with numerous minute spots of bright yellow: the former of these varied in intensity; the latter entirely disappeared and appeared again by turns.

These clouds, or blushes as they may be called, are said to be produced by the alternate expansion and contraction of minute vesicles containing variously coloured fluids.The term chromatophore was adopted (following Sangiovanni's chromoforo) as the name for pigment-bearing cells derived from the neural crest of cold-blooded vertebrates and cephalopods.

It is found primarily in red blood cells (erythrocytes), which are generated in bone marrow throughout the life of an organism, rather than being formed during embryological development.

[citation needed] Chromatophores that contain large amounts of yellow pteridine pigments are named xanthophores; those with mainly red/orange carotenoids are termed erythrophores.

Most chromatophores can generate pteridines from guanosine triphosphate, but xanthophores appear to have supplemental biochemical pathways enabling them to accumulate yellow pigment.

Fish iridophores are typically stacked guanine plates separated by layers of cytoplasm to form microscopic, one-dimensional, Bragg mirrors.

[13] Some species of anole lizards, such as the Anolis grahami, use melanocytes in response to certain signals and hormonal changes, and is capable of becoming colors ranging from bright blue, brown, and black.

This was subsequently identified as pterorhodin, a pteridine dimer that accumulates around eumelanin core, and it is also present in a variety of tree frog species from Australia and Papua New Guinea.

However, some types of Synchiropus splendidus do possess vesicles of a cyan biochrome of unknown chemical structure in cells named cyanophores.

Likewise, after melanin aggregation in DCUs, the skin appears green through xanthophore (yellow) filtering of scattered light from the iridophore layer.

[11][20] It has been demonstrated that the process can be under hormonal or neuronal control or both and for many species of bony fishes it is known that chromatophores can respond directly to environmental stimuli like visible light, UV-radiation, temperature, pH, chemicals, etc.

This type of camouflage, known as background adaptation, most commonly appears as a slight darkening or lightening of skin tone to approximately mimic the hue of the immediate environment.

[23] Some animals, such as chameleons and anoles, have a highly developed background adaptation response capable of generating a number of different colours very rapidly.

[33] They have adapted the capability to change colour in response to temperature, mood, stress levels, and social cues, rather than to simply mimic their environment.

These cells have the ability to migrate long distances, allowing chromatophores to populate many organs of the body, including the skin, eye, ear, and brain.

[citation needed] When and how multipotent chromatophore precursor cells (called chromatoblasts) develop into their daughter subtypes is an area of ongoing research.

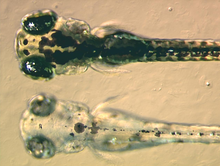

For example, zebrafish larvae are used to study how chromatophores organise and communicate to accurately generate the regular horizontal striped pattern as seen in adult fish.

Recently, the gene responsible for the melanophore-specific golden zebrafish strain, Slc24a5, was shown to have a human equivalent that strongly correlates with skin colour.

[32] Human homologues of receptors that mediate pigment translocation in melanophores are thought to be involved in processes such as appetite suppression and tanning, making them attractive targets for drugs.

[26] Therefore, pharmaceutical companies have developed a biological assay for rapidly identifying potential bioactive compounds using melanophores from the African clawed frog.

[40] Potential military applications of chromatophore-mediated colour changes have been proposed, mainly as a type of active camouflage, which could as in cuttlefish make objects nearly invisible.

[44] Octopuses and most cuttlefish[45] can operate chromatophores in complex, undulating chromatic displays, resulting in a variety of rapidly changing colour schemata.