Isaac Asimov

[7] Several entities have been named in his honor, including the asteroid (5020) Asimov,[8] a crater on Mars,[9][10] a Brooklyn elementary school,[11] Honda's humanoid robot ASIMO,[12] and four literary awards.

Now leave out the two h's and say it again and you have Asimov.Asimov's family name derives from the first part of озимый хлеб (ozímyj khleb), meaning 'winter grain' (specifically rye) in which his great-great-great-grandfather dealt, with the Russian surname ending -ov added.

[50] In 1946, a bureaucratic error caused his military allotment to be stopped, and he was removed from a task force days before it sailed to participate in Operation Crossroads nuclear weapons tests at Bikini Atoll.

[52][f] After completing his doctorate and a postdoctoral year with Robert Elderfield,[54] Asimov was offered the position of associate professor of biochemistry at the Boston University School of Medicine.

This was in large part due to his years-long correspondence with William Boyd, a former associate professor of biochemistry at Boston University, who initially contacted Asimov to compliment him on his story Nightfall.

[75][h] In the third volume of his autobiography, he recalls a childhood desire to own a magazine stand in a New York City Subway station, within which he could enclose himself and listen to the rumble of passing trains while reading.

[78] He sailed to England in June 1974 on the SS France for a trip mostly devoted to lectures in London and Birmingham,[79] though he also found time to visit Stonehenge[80] and Shakespeare's birthplace.

[89] He was a prominent member of The Baker Street Irregulars, the leading Sherlock Holmes society,[78] for whom he wrote an essay arguing that Professor Moriarty's work "The Dynamics of An Asteroid" involved the willful destruction of an ancient, civilized planet.

He was also a member of the male-only literary banqueting club the Trap Door Spiders, which served as the basis of his fictional group of mystery solvers, the Black Widowers.

[96] In a discussion with James Randi at CSICon 2016 regarding the founding of CSICOP, Kendrick Frazier said that Asimov was "a key figure in the Skeptical movement who is less well known and appreciated today, but was very much in the public eye back then."

Campbell rejected it on July 22 but—in "the nicest possible letter you could imagine"—encouraged him to continue writing, promising that Asimov might sell his work after another year and a dozen stories of practice.

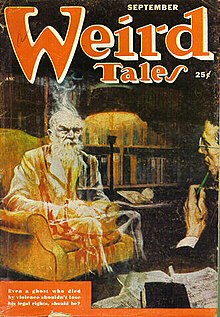

[61][126] Two more stories appeared that year, "The Weapon Too Dreadful to Use" in the May Amazing and "Trends" in the July Astounding, the issue fans later selected as the start of the Golden Age of Science Fiction.

"[134] "Nightfall" is an archetypal example of social science fiction, a term he created to describe a new trend in the 1940s, led by authors including him and Heinlein, away from gadgets and space opera and toward speculation about the human condition.

They feature his fictional science of psychohistory, whose theories could predict the future course of history according to dynamical laws regarding the statistical analysis of mass human actions.

Besides movies, his Foundation and Robot stories have inspired other derivative works of science fiction literature, many by well-known and established authors such as Roger MacBride Allen, Greg Bear, Gregory Benford, David Brin, and Donald Kingsbury.

"[161] Asimov's first wide-ranging reference work, The Intelligent Man's Guide to Science (1960), was nominated for a National Book Award, and in 1963 he won a Hugo Award—his first—for his essays for F&SF.

[172] Asimov coined the term "psychohistory" in his Foundation stories to name a fictional branch of science which combines history, sociology, and mathematical statistics to make general predictions about the future behavior of very large groups of people, such as the Galactic Empire.

Complete with maps and tables, the guide goes through the books of the Bible in order, explaining the history of each one and the political influences that affected it, as well as biographical information about the important characters.

He got the idea for the Widowers from his own association in a stag group called the Trap Door Spiders, and all of the main characters (with the exception of the waiter, Henry, who he admitted resembled Wodehouse's Jeeves) were modeled after his closest friends.

According to Asimov, the most essential element of humor is an abrupt change in point of view, one that suddenly shifts focus from the important to the trivial, or from the sublime to the ridiculous.

However, by 2016, Asimov's habit of groping women was seen as sexual harassment and came under criticism, and was cited as an early example of inappropriate behavior that can occur at science fiction conventions.

Asimov corrected himself with a follow-up essay to TV Guide claiming that despite its inaccuracies, Star Trek was a fresh and intellectually challenging science fiction television show.

The director criticizes the fictionalized Asimov ("Gregory Laborian") for having an extremely nonvisual style, making it difficult to adapt his work, and the author explains that he relies on ideas and dialogue rather than description to get his points across.

Asimov continued to identify himself as a secular Jew, as stated in his introduction to Jack Dann's anthology of Jewish science fiction, Wandering Stars: "I attend no services and follow no ritual and have never undergone that curious puberty rite, the Bar Mitzvah.

"[254] In his last volume of autobiography, Asimov wrote, If I were not an atheist, I would believe in a God who would choose to save people on the basis of the totality of their lives and not the pattern of their words.

Asimov's impression was that the 1960s' counterculture heroes had ridden an emotional wave which, in the end, left them stranded in a "no-man's land of the spirit" from which he wondered if they would ever return.

[270] Additional specific incidents were reported by other people including Edward L. Ferman, long-time editor of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, who wrote "...instead of shaking my date's hand, he shook her left breast".

His last nonfiction book, Our Angry Earth (1991, co-written with his long-time friend, science fiction author Frederik Pohl), deals with elements of the environmental crisis such as overpopulation, oil dependence, war, global warming, and the destruction of the ozone layer.

[164] The feelings of friendship and respect between Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke were demonstrated by the so-called "Clarke–Asimov Treaty of Park Avenue", negotiated as they shared a cab in New York.

[291] An online exhibit in West Virginia University Libraries' virtually complete Asimov Collection displays features, visuals, and descriptions of some of his more than 600 books, games, audio recordings, videos, and wall charts.