Weird Tales

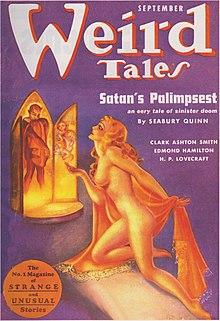

[1] The first editor, Edwin Baird, printed early work by H. P. Lovecraft, Seabury Quinn, and Clark Ashton Smith, all of whom went on to be popular writers, but within a year, the magazine was in financial trouble.

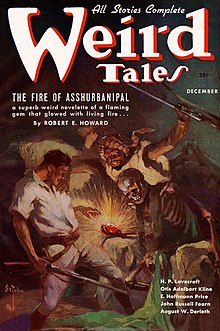

Edmond Hamilton wrote a good deal of science fiction for Weird Tales, though after a few years, he used the magazine for his more fantastic stories, and submitted his space operas elsewhere.

Although some successful new authors and artists, such as Ray Bradbury and Hannes Bok, continued to appear, the magazine is considered by critics to have declined under McIlwraith from its heyday in the 1930s.

[2] Weinberg's fellow historian, Mike Ashley, describes it as "second only to Unknown in significance and influence",[3] adding that "somewhere in the imagination reservoir of all U.S. (and many non-U.S.) genre-fantasy and horror writers is part of the spirit of Weird Tales".

Mike Ashley, a science fiction magazine historian, records that Moskowitz was unwilling to continue in any case, as he was annoyed by Margulies's detailed involvement in the day-to-day editorial tasks such as editing manuscripts and writing introductions.

Forbes' editorial director was Gordon Garb and the fiction editor was Gil Lamont; Forrest Ackerman also assisted, mainly by obtaining material to include.

There was a good deal of confusion between the participants in the project:[56] according to Locus, a science fiction trade journal, "Ackerman says he has had no contact with publisher Forbes, does not know what will happen to the material he put together, and is as much in the dark as everybody else.

[56] Weird Tales was more lastingly revived at the end of the 1980s by George H. Scithers, John Gregory Betancourt and Darrell Schweitzer, who formed Terminus Publishing, based in Philadelphia, and licensed the rights from Weinberg.

A special World Fantasy Award Weird Tales received in 1992 made it apparent that the magazine was successful in terms of quality, but sales were insufficient to cover costs.

[60] No issues appeared in 1997, but in 1998 Scithers and Schweitzer negotiated a deal with Warren Lupine of DNA Publications which allowed them to start publishing Weird Tales under license once again.

Wildside Press, owned by John Betancourt, joined DNA and Terminus Publishing as co-publisher, starting with the July/August 2003 issue, and Weird Tales returned to a mostly regular schedule for a few months.

In early 2007, Wildside announced a revamp of Weird Tales, naming Stephen H. Segal the editorial and creative director and later recruiting Ann VanderMeer as the new fiction editor.

He later recalled talking to three well-known Chicago writers, Hamlin Garland, Emerson Hough, and Ben Hecht, each of whom had said they avoided writing stories of "fantasy, the bizarre, and the outré" because of the likelihood of rejection by existing markets.

[10] He added "I must confess that the main motive in establishing Weird Tales was to give the writer free rein to express his innermost feelings in a manner befitting great literature",[10] but it is unlikely any of these authors promised to submit anything to Henneberger.

[68] Edwin Baird, the first editor of Weird Tales, was not an ideal choice for the job as he disliked horror stories; his expertise was in crime fiction, and most of the material he acquired was bland and unoriginal.

Over time other writers began to contribute their own stories with the same shared background, including Frank Belknap Long, August Derleth, E. Hoffmann Price, and Donald Wandrei.

[91][notes 8] Edmond Hamilton, a leading early writer of space opera, became a regular, and Wright also published science fiction stories by J. Schlossel and Otis Adelbert Kline.

[89] Although Wright's editorial standards were broad, and although he personally disliked the restrictions that convention placed on what he could publish, he did exercise caution when presented with material that might offend his readership.

[97] Wright turned down Lovecraft's novel At the Mountains of Madness in 1935, though in this case it was probably because of the story's length—running a serial required paying an author for material that would not appear until two or three issues later, and Weird Tales often had little cash to spare.

Quinn was Weird Tales' most prolific author, with a long-running sequence of stories about a detective, Jules de Grandin, who investigated supernatural events, and for a while he was the most popular writer in the magazine.

[notes 9] Other regular contributors included Paul Ernst, David H. Keller, Greye La Spina, Hugh B. Cave, and Frank Owen, who wrote fantasies set in an imaginary version of the Far East.

[111] Not every artist was as successful as Brundage and Finlay: Price suggested that Curtis Senf, who painted 45 covers early in Wright's tenure, "was one of Sprenger's bargains", meaning that he produced poor art, but worked fast for low rates.

[35] By the end of Wright's tenure as editor, many of the writers who had become strongly associated with the magazine were gone; Kuttner, and others such as Price and Moore, were still writing, but Weird Tales' rates were too low to attract submissions from them.

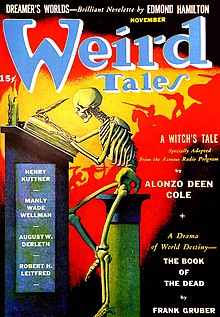

[126][notes 11] McIlwraith continued to publish many of Weird Tales' most popular authors, including Quinn, Derleth, Hamilton, Bloch, and Manly Wade Wellman.

With Stephen H. Segal as editorial and creative director and Ann VanderMeer as fiction editor,[51] during the next few years the magazine "won a number of awards and great acclaim.

[51][142] During this time Weird Tales published works by a wide range of strange-fiction authors including Michael Moorcock and Tanith Lee, as well as newer writers such as N. K. Jemisin, Jay Lake, Cat Rambo, and Rachel Swirsky.

[144][145] In addition to winning or being nominated for awards, under VanderMeer's editorship Weird Tales saw the number of subscriptions triple as the magazine "came to symbolise what was good about the changes in the SF community.

[62] In August 2012, Weird Tales became involved in a media altercation after Kaye announced the magazine was going to publish an excerpt from Victoria Foyt's controversial novel Save the Pearls, which many critics accused of featuring racist stereotyping.

[156] Justin Everett and Jeffrey H. Shanks, the editors of a recent scholarly collection of literary criticism focused on the magazine, argue that "Weird Tales functioned as a nexus point in the development of speculative fiction from which emerged the modern genres of fantasy and horror".

[160] Everett and Shanks agree, and regard Weird Tales as the venue where writers, editors and an engaged readership "elevated speculated fiction to new heights" with influence that "reverberates through modern popular culture".