Islamic influences on Western art

Western European Christians interacted with Muslims in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East and formed a relationship based on shared ideas and artistic methods.

Islamic architecture, however, appeared to influence the designs of Templar churches within the Middle East and other cathedrals within Europe upon the return of Crusaders in the 12th and 13th century.

Techniques included inlays in mosaics or metals, often used for architectural decoration, porphyry or ivory carving to create sculptures or containers, and bronze foundries.

During the late centuries of the Reconquista Christian craftsmen started using Islamic artistic elements in their buildings, as a result the Mudéjar style was developed.

[6] Instead of wall-paintings, Islamic art used painted tiles, from as early as 862-3 (at the Great Mosque of Kairouan in modern Tunisia), which also spread to Europe.

[7] According to John Ruskin, the Doge's Palace in Venice contains "three elements in exactly equal proportions — the Roman, the Lombard, and Arab.

[8] Throughout the Middle Ages, Islamic rulers controlled at various points parts of Southern Italy, the island of Sicily, and most of modern Spain and Portugal, as well as the Balkans, all of which retained large Christian populations.

For example, in the Romanesque portal at Moissac in southern France, the scalloped edges to the doorway and the circular decorations on the lintel above, have parallels in Iberian Islamic art.

The depiction of Christ in Majesty surrounded by musicians, which was to become a common feature of Western heavenly scenes, may derive from courtly images of Islamic rulers.

Until the end of the Middle Ages, many European produced goods could not match the quality of objects originating from areas in the Islamic world or the Byzantine Empire.

Because of this, a wide variety of portable objects from various decorative arts were imported from the Islamic world into Europe during the Middle Ages, mostly through Italy, and above all Venice.

Luxury textiles were widely used for clothing and hangings and also, fortunately for art history, also often as shrouds for the burials of important figures, which is how most surviving examples were preserved.

The Normans of Sicily were located at a crossroads between European Christian cultures, and the Islamic worlds of Spain, North Africa, Western Asia.

[25] Christian buildings such as the Cappella Palatina in Palermo, Sicily, incorporated Islamic elements, probably usually created by local Muslim craftsmen working in their own traditions.

[28] William Hamilton commented on the Seljuks monuments in Konya: "The more I saw of this peculiar style, the more I became convinced that the Gothic was derived from it, with a certain mixture of Byzantine (...) the origin of this Gotho-Saracenic style may be traced to the manners and habits of the Saracens"[N 3][29] The 8th century Umayyad Caliphate within the Iberian peninsula was credited with introducing many elements adopted into Gothic architecture within Spain, and Christian Crusaders returning home to Europe in the 12th and 13th century carried Islamic architectural influences with them into France and later England.

The 18th-century English historian Thomas Warton summarized: "The marks which constitute the character of Gothic or Saracenical architecture, are, its numerous and prominent buttresses, its lofty spires and pinnacles, its large and ramified windows, its ornamental niches or canopies, its sculptured saints, the delicate lace-work of its fretted roofs, and the profusion of ornaments lavished indiscriminately over the whole building: but its peculiar distinguishing characteristics are, the small cluttered pillars and pointed arches, formed by the segments of two interfering circles"When Sir.

[3] Wren’s attribution of the Gothic’s style’s pointed arch to Islamic architecture was affirmed by 21st century scholar Diana Darke, who in Stealing from the Saracens: How Islamic Architecture Shaped Europe explains that the pointed arch first appeared in the 7th century Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, which was built by the Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik.

[3] Furthermore, the trefoil arch, which was adopted by Gothic architects to symbolize the Holy Trinity, first appeared within Umayyad shrines and palaces before it was seen in European architecture.

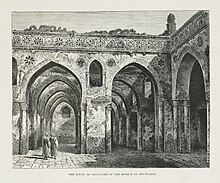

[33] In 1119, the Knights Templar received as headquarters part of the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, considered by the crusaders the Temple of Solomon, from which the order took its common name.

Subsequently, the Templar order built secular and religious structures within the mosque’s area, like multiple cloisters, shrines, and a church.

[38] Mack states another hypothesis: Perhaps they marked the imagery of a universal faith, an artistic intention consistent with the Church's contemporary international program.

These basic motifs gave rise to numerous variants, for example, where the branches, generally of a linear character, were turned into straps or bands.

Originating in the Middle East, they were introduced to continental Europe via Italy and Spain ... Italian examples of this ornament, which was often used for bookbindings and embroidery, are known from as early as the late fifteenth century.

Many of the settlers from Spain were craftsmen and builders that converted to Christianity from Islam, bringing "domes, eight-pointed stars, quatrefoil elements, ironwork, courtyard fountains, balconies, towers, and colorful tiles" as noted by historian Phil Pasquini.