Mathematics in the medieval Islamic world

Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwārizmī played a key role in this transformation, introducing algebra as a distinct field in the 9th century.

[2] Arabic mathematical knowledge spread through various channels during the medieval era, driven by the practical applications of Al-Khwārizmī's methods.

The Islamic Golden Age, spanning from the 8th to the 14th century, marked a period of considerable advancements in various scientific disciplines, attracting scholars from medieval Europe seeking access to this knowledge.

The translation of Arabic mathematical texts, along with Greek and Roman works, during the 14th to 17th century, played a pivotal role in shaping the intellectual landscape of the Renaissance.

Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwārizmī's (Arabic: محمد بن موسى الخوارزمي; c. 780 – c. 850) work between AD 813 and 833 in Baghdad was a turning point.

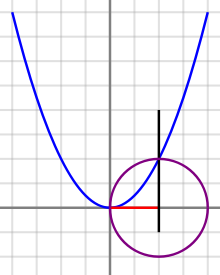

Al-Khwārizmī's proof of the rule for solving quadratic equations of the form (ax^2 + bx = c), commonly referred to as "squares plus roots equal numbers," was a monumental achievement in the history of algebra.

This breakthrough laid the groundwork for the systematic approach to solving quadratic equations, which became a fundamental aspect of algebra as it developed in the Western world.

[4] Al-Khwārizmī's method, which involved completing the square, not only provided a practical solution for equations of this type but also introduced an abstract and generalized approach to mathematical problems.

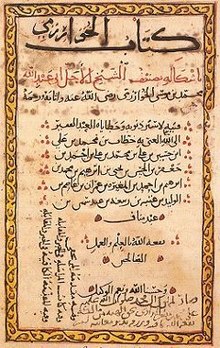

His work, encapsulated in his seminal text "Al-Kitab al-Mukhtasar fi Hisab al-Jabr wal-Muqabala" (The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing), was translated into Latin in the 12th century.

This translation played a pivotal role in the transmission of algebraic knowledge to Europe, significantly influencing mathematicians during the Renaissance and shaping the evolution of modern mathematics.

Its spread to the West was driven by its practical applications, the expansion of mathematical concepts by his successors, and the translation and adaptation of these ideas into the Western context.

European scholars who traveled to the Holy Land and other parts of the Islamic world gained access to Arabic manuscripts and mathematical treatises.

During the 14th to 17th century, the translation of Arabic mathematical texts, along with Greek and Roman ones, played a crucial role in shaping the intellectual landscape of the Renaissance.

Figures like Fibonacci, who studied in North Africa and the Middle East, helped introduce and popularize Arabic numerals and mathematical concepts in Europe.

The study of algebra, the name of which is derived from the Arabic word meaning completion or "reunion of broken parts",[6] flourished during the Islamic golden age.

In between, implicit proof by induction for arithmetic sequences was introduced by al-Karaji (c. 1000) and continued by al-Samaw'al, who used it for special cases of the binomial theorem and properties of Pascal's triangle.

[18] In the twelfth century, Latin translations of Al-Khwarizmi's Arithmetic on the Indian numerals introduced the decimal positional number system to the Western world.

[25]Between the 9th and 10th centuries, the Egyptian mathematician Abu Kamil wrote a now-lost treatise on the use of double false position, known as the Book of the Two Errors (Kitāb al-khaṭāʾayn).

The oldest surviving writing on double false position from the Middle East is that of Qusta ibn Luqa (10th century), an Arab mathematician from Baalbek, Lebanon.

"The Moors (western Mohammedans from that part of North Africa once known as Mauritania) crossed over into Spain early in the seventh century, bringing with them the cultural resources of the Arab world".

European scholars such as Gerard of Cremona (1114–1187) played a key role in translating and disseminating these works, thus making them accessible to a wider audience.

He was "the first in history to elaborate a geometrical theory of equations with degrees ≤ 3",[30] and has great influence on the work of Descartes, a French mathematician who is often regarded as the founder of analytical geometry.

Indeed, "to read Descartes' Géométrie is to look upstream towards al-Khayyām and al-Ṭūsī; and downstream towards Newton, Leibniz, Cramer, Bézout and the Bernoulli brothers".

[31] Abū Kāmil's Algebra plays a significant role in shaping the trajectory of Western mathematics, particularly in its impact on the works of the Italian mathematician Leonardo of Pisa, widely recognized as Fibonacci.

In his Liber Abaci (1202), Fibonacci extensively incorporated ideas from Arabic mathematicians, using approximately 29 problems from Book of Algebra with scarce modification.

In the French philosopher Ernest Renan's work, Arabic math is merely "a reflection of Greece, combined with Persian and Indian influences".

Furthermore, strictly dependent on Greek science and, lastly, incapable of introducing experimental norms, scientists of that time were relegated to the role of conscientious guardians of the Hellenistic museum.

The medieval Arab-Islamic world played a crucial role in shaping the trajectory of mathematics, with al-Khwārizmī's algebraic innovations serving as a cornerstone.

Despite the foundational contributions of Arab mathematicians, Western historians in the 18th and early 19th centuries, influenced by Orientalist views, sometimes marginalized these achievements.

The contributions of Arab mathematicians, marked by practical applications and theoretical innovations, form an integral part of the rich tapestry of mathematical history, and deserves recognition.