Physics in the medieval Islamic world

However the Islamic world had a greater respect for knowledge gained from empirical observation, and believed that the universe is governed by a single set of laws.

[1] Al-Kindi argued against the idea of the cosmos being eternal by claiming that the eternality of the world lands one in a different sort of absurdity involving the infinite; Al-Kindi asserted that the cosmos must have a temporal origin because traversing an infinite was impossible.

[13] It was a different approach than that which was previously thought by Greek scientists, such as Euclid or Ptolemy, who believed rays were emitted from the eye to an object and back again.

[12] Taqī al-Dīn tried to disprove the widely held belief that light is emitted by the eye and not the object that is being observed.

It was not always accurate in its predictions and was over complicated because astronomers were trying to mathematically describe the movement of the heavenly bodies.

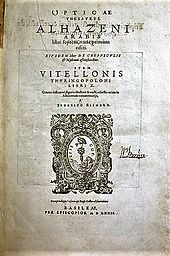

Ibn al-Haytham published Al-Shukuk ala Batiamyus ("Doubts on Ptolemy"), which outlined his many criticisms of the Ptolemaic paradigm.

[16] In al-Haytham's Book of Optics he argues that the celestial spheres were not made of solid matter, and that the heavens are less dense than air.

[18] John Philoponus had rejected the Aristotelian view of motion, and argued that an object acquires an inclination to move when it has a motive power impressed on it.

In the eleventh century Ibn Sina had roughly adopted this idea, believing that a moving object has force which is dissipated by external agents like air resistance.

[20] This idea which dissented from the Aristotelian view was basically abandoned until it was described as "impetus" by John Buridan, who may have been influenced by Ibn Sina.

[19][21] In Abū Rayḥān al-Bīrūnī text Shadows, he recognizes that non-uniform motion is the result of acceleration.