Isomer

The depth of analysis depends on the field of study or the chemical and physical properties of interest.

The English word "isomer" (/ˈaɪsəmər/) is a back-formation from "isomeric",[2] which was borrowed through German isomerisch[3] from Swedish isomerisk; which in turn was coined from Greek ἰσόμερoς isómeros, with roots isos = "equal", méros = "part".

The alcohol "3-propanol" is not another isomer, since the difference between it and 1-propanol is not real; it is only the result of an arbitrary choice in the direction of numbering the carbons along the chain.

Tautomers are structural isomers which readily interconvert, so that two or more species co-exist in equilibrium such as

[6] Important examples are keto-enol tautomerism and the equilibrium between neutral and zwitterionic forms of an amino acid.

The corresponding energy barrier between the two conformations is so high that there is practically no conversion between them at room temperature, and they can be regarded as different configurations.

, in contrast, is not chiral: the mirror image of its molecule is also obtained by a half-turn about a suitable axis.

The double bonds are such that the three middle carbons are in a straight line, while the first three and last three lie on perpendicular planes.

For this latter reason, the two enantiomers of most chiral compounds usually have markedly different effects and roles in living organisms.

In biochemistry and food science, the two enantiomers of a chiral molecule – such as glucose – are usually identified, and treated as very different substances.

Each enantiomer of a chiral compound typically rotates the plane of polarized light that passes through it.

The rotation has the same magnitude but opposite senses for the two isomers, and can be a useful way of distinguishing and measuring their concentration in a solution.

[10][11] Some enantiomer pairs (such as those of trans-cyclooctene) can be interconverted by internal motions that change bond lengths and angles only slightly.

(a six-fold alcohol of cyclohexane), the six-carbon cyclic backbone largely prevents the hydroxyl

The most common one in nature (myo-inositol) has the hydroxyls on carbons 1, 2, 3 and 5 on the same side of that plane, and can therefore be called cis-1,2,3,5-trans-4,6-cyclohexanehexol.

Cis and trans isomers also occur in inorganic coordination compounds, such as square planar

In such cases, a more precise labeling scheme is employed based on the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog priority rules.

) on an ethane molecule yields two distinct structural isomers, depending on whether the substitutions are both on the same carbon (1,1-dideuteroethane,

Another type of isomerism based on nuclear properties is spin isomerism, where molecules differ only in the relative spin magnetic quantum numbers ms of the constituent atomic nuclei.

Isomers having distinct biological properties are common; for example, the placement of methyl groups.

In substituted xanthines, theobromine, found in chocolate, is a vasodilator with some effects in common with caffeine; but, if one of the two methyl groups is moved to a different position on the two-ring core, the isomer is theophylline, which has a variety of effects, including bronchodilation and anti-inflammatory action.

In medicinal chemistry and biochemistry, enantiomers are a special concern because they may possess distinct biological activity.

Many preparative procedures afford a mixture of equal amounts of both enantiomeric forms.

As an inorganic example, cisplatin (see structure above) is an important drug used in cancer chemotherapy, whereas the trans isomer (transplatin) has no useful pharmacological activity.

Isomerism was first observed in 1827, when Friedrich Wöhler prepared silver cyanate and discovered that, although its elemental composition of

was identical to silver fulminate (prepared by Justus von Liebig the previous year),[20] its properties were distinct.

Additional examples were found in succeeding years, such as Wöhler's 1828 discovery that urea has the same atomic composition (

In 1830 Jöns Jacob Berzelius introduced the term isomerism to describe the phenomenon.

[4][21][22][23] In 1848, Louis Pasteur observed that tartaric acid crystals came into two kinds of shapes that were mirror images of each other.

[24][25] In 1860, Pasteur explicitly hypothesized that the molecules of isomers might have the same composition but different arrangements of their atoms.

3 H

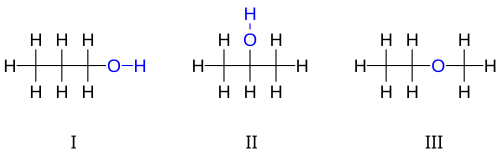

8 O : I 1-propanol, II 2-propanol, III ethyl-methyl-ether.