Isaac Brock

Brock's actions, particularly his success at Detroit, earned him accolades including a knighthood in the Order of the Bath and the sobriquet "The Hero of Upper Canada".

Lacking special political connections, Brock's ability to gain promotions even when the nation was at peace attests to his skills in recruiting men and organising finances, and ambition.

"[23] After a period of leave in England over winter 1805–1806 and promotion to colonel on 29 October 1805,[24] Brock returned to Canada temporarily in command of the entire British army there.

At the same time, the US leaders believed that the growing population needed new territory; some imagined that the United States was destined to control all of the North American continent.

American hawks assumed that Canadian colonists would rise up and support the invading U.S. armies as liberators and that, as Thomas Jefferson famously wrote, conquering Canada would be "a mere matter of marching".

Brock succeeded in creating a formidable defensive position due largely to his military reading, which included several volumes on the science of running and setting up artillery.

When permission to leave for Europe finally came in early 1812, Brock declined the offer, believing he had a duty to defend Canada in war against the United States.

Although the conventional wisdom of the day was that Canada would fall quickly in the event of an invasion, Brock pursued these strategies to give the colony a fighting chance.

Brock's advantage was that the armed vessels of the Provincial Marine controlled the lakes, and allowed him to move his reserves rapidly between threatened points.

When news of the outbreak of war reached him, he sent a canoe party under the noted trader and voyager William McKay to the British outpost at St. Joseph Island on Lake Huron.

His orders to commander (Captain Charles Roberts) allowed him to stand on the defensive or attack the nearby American outpost at Fort Mackinac at his discretion.

He wrote to Prevost's adjutant general, My situation is most critical, not from anything the enemy can do, but from the disposition of the people – The Population, believe me is essentially bad – A full belief possesses them that this Province must inevitably succumb – This Prepossession is fatal to every exertion – Legislators, Magistrates, Militia Officers, all, have imbibed the idea, and are so sluggish and indifferent in all their respective offices that the artful and active scoundrel is allowed to parade the Country without interruption, and commit all imaginable mischief... What a change an additional regiment would make in this part of the Province!

Having finally obtained limited support from the legislature for his measures to defend the Province, Brock prorogued the Assembly and set out on 6 August with a small body of regulars and some volunteers from the York Militia (the "York Volunteers") to reinforce the garrison at Fort Malden – Amherstburg at the western end of Lake Erie, facing Hull's position at Detroit.

He had Tecumseh's forces cross in front of the fort several times (doubling back under cover), intimidating Hull with the show of a large, raucous, barely controlled group of First Nations warriors.

Finally, he sent Hull a letter demanding his surrender, in which he stated, in part, "It is far from my inclination to join in a war of extermination, but you must be aware that the numerous body of Indians who have attached themselves to my troops will be beyond my control the moment the contest commences.

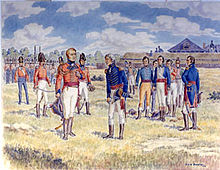

[3][40] Although Brock's correspondence indicates a certain amount of paternal condescension for the First Nations,[Note 3] he seems to have regarded Tecumseh very highly,[41] calling him "the Wellington of the Indians",[40] and saying "a more sagacious or a more gallant warrior does not I believe exist".

Despite heavy fire from British artillery, the first wave of Americans (under Captain John E. Wool) managed to land, and then follow a fishermen's path up to the heights.

[45] The assault was halted by heavy fire and as he noticed unwounded men dropping to the rear, Brock shouted angrily that "This is the first time I have ever seen the 49th turn their backs!

His height and energetic gestures, together with his officer's uniform and a gaudy sash given to him eight weeks earlier by Tecumseh after the siege of Detroit,[48] made him a conspicuous target.

(Latin for "rise" or "push on" – now used as a motto by Brock University), and even "a request that his fall might not be noticed or prevent the advance of his brave troops, adding a wish, which could not be distinctly understood, that some token of remembrance should be transmitted to his sister.

"[51] These accounts are considered unlikely, since he was not in the company of the York Volunteers but regular soldiers at the time and it is also reported that Brock died almost immediately without speaking,[52] and the hole in his uniform suggests that the bullet entered his heart.

[4] His body was carried from the field and secreted in a nearby house at the corner of Queenston and Partition streets, diagonally opposite that of Laura Secord.

[57] Carrying Macdonnell and the body of Brock, the British fell back through Queenston to Durham's Farm, a mile north near Vrooman's Point.

On 16 October, a funeral procession for Brock and Colonel Macdonell went from Government House to Fort George, with soldiers from the British Army, the colonial militia, and First Nations warriors on either side of the route.

He was criticised by many, including John Strachan, for his retreat at the Battle of York, and was shortly after recalled to England, where he continued a successful, if not brilliant, military career.

When he finally did attack, his forces proved unable to cross the Saranac River bridge, which was held by a small group of American regulars under the command of the recently promoted John E. Wool.

[68] A British naval vessel named in his honour, HMS Sir Isaac Brock, was destroyed at the Battle of York while under construction to prevent it falling into enemy hands.

The horse was supposedly shot and killed during the battle while being ridden by Macdonell, and it is commemorated in a monument erected in 1976 in Queenston near the cairn marking the spot where Brock fell.

Private copper tokens became common in Canada due to initial distrust of "army bills", paper notes issued by Brock when there was a currency shortage caused by economic growth.

[77] In September 2012, the Royal Canadian Mint issued a .99999 pure gold coin with a face value of 350 dollars to honor the bicentenary of Brock's death.