Istrian Italians

Istrian Italians descend from the original Latinized population of Roman Histria, from the Venetian-speaking settlers who colonized the region during the time of the Republic of Venice, and from the local Croatian people who culturally assimilated.

The number of people resident in the Croatian part of Istria declaring themselves to be Italian nearly doubled between 1981 and 1991 (i.e. before and after the dissolution of Yugoslavia).

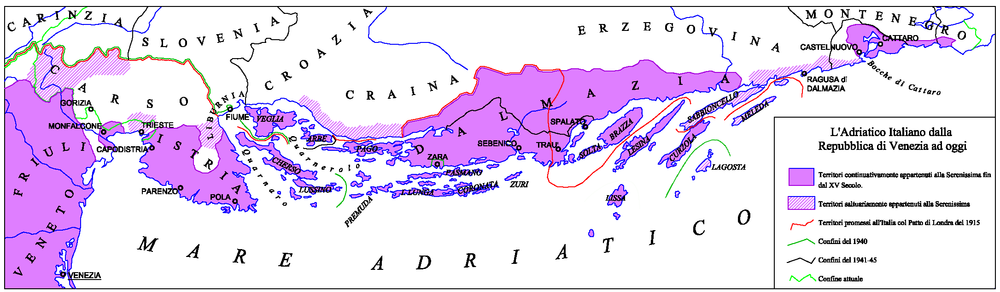

[10] Republic of Venice influenced the neolatins of Istria for many centuries from the Middle Ages until 1797, until conquered by Napoleon: Capodistria and Pola were important centres of art and culture during the Italian Renaissance.

As a consequence of depopulation, Venice started settling Slavic communities to repopulate the interior areas of the peninsula.

These were mostly Čakavian and partially Štokavian speaking South Slavs from Dalmatia and present-day Montenegro (differently from Kajkavian and proto-Slovene speakers that lived in the northern areas of the peninsula).

In 1374 Because of the implementation of a treaty of inheritance, central and eastern Istria fell to the House of Habsburg, while Venice continued to control the northern, western and south-eastern portion of the peninsula, including the major coastal towns of Capodistria / Koper, Parenzo / Poreč, Rovigno / Rovinj, Pola / Pula, Fianona / Plomin, and the interior towns of Albona / Labin and Pinguente / Buzet.

As a result, Istrian Italians became a minority in the new administrative unit, although they maintained their social and part of their political power.

[13] Although the incorporation into the Austrian Empire caused deep changes in the political assets of the region, it did not alter the social balance.

In the first half of the 19th century, the use of the Venetian language even extended to some areas of former Austrian Istria, like the town of Pazin / Pisino.

[citation needed] However, after 1866, when the Veneto and Friuli regions were ceded by the Austrians to the newly formed Kingdom Italy, Istria remained part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, together with other Italian-speaking areas on the eastern Adriatic (Trieste, Gorizia and Gradisca, Fiume).

His Majesty calls the central offices to the strong duty to proceed in this way to what has been established.This tension created - by some claims - a "huge" emigration of Italians from Istria before World War I, reducing their percentage inside the peninsula inhabitants (there are some claims Italians made more than 50% of the total population for centuries,[19] but at the end of the 19th century they were reduced to only two fifths according to some estimates).

D'Alessio notes even the people who immigrated from non-Croatian and non-Italian parts of the Habsburg Empire tended to use Italian, after living in Istrian towns long enough.

The result was the intensification of the ethnic strife between the two groups, although it was limited to institutional battles and it rarely manifested in violent forms.

Until the end of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, the bourgeois Italian national liberal elites retained much of the political control in Istria.

However, ethnic tensions grew, and a Slovenian and Croatian anti-Fascist insurgency started to appear in the late 1920s, although it was much less strong than in other parts of the Julian March.

The Austrian 1910 census indicated approximately 182,500 people who listed Italian as their language of communication in what is now the territory of Slovenia and Croatia: 137,131 in Istria and 28,911 in Fiume/Rijeka (1918).

This emigration of Italians (called Istrian–Dalmatian exodus) reduced the total population of the region and altered its ethnic structure.

Only the north-western portion was assigned to zone B of the short-lived Free Territory of Trieste, but de facto remained under Yugoslav administration.

This triggered the last wave of the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus, with most of the Istrian Italians[27][28] leaving the zone B for elsewhere (mainly to Italy) because intimidated or preferring not to live in communist Yugoslavia.

Not surprisingly in 2001 (i.e. after the dissolution of Yugoslavia), the Croatian and Slovenian censuses reported a total Italian population of 21,894 (with the figure in Croatia nearly doubling).

In its 1996 report on 'Local self-government, territorial integrity and protection of minorities' the Council of Europe's European Commission for Democracy through Law (the Venice Commission) put it that "a great majority of the local Italians, some thousands of Slovenes and of nationally undefined bilingual 'Istrians', used their legal right from the peace treaty to 'opt out' of the Yugoslav controlled part of Istria".

Croatian municipalities with a significant Italian population include Grisignana / Grožnjan (36%), Verteneglio / Brtonigla (32%), and Buie / Buje (24%).

This applies to dances done by the modern-day Croatian population and by the Italian national minority found today in the larger towns and some villages in the western part of Istria.

According to the most accredited thesis, "Jota" derives from the Latin jutta (meaning broth)[43] and has parallels in the ancient friulan language and in modern emilian-romagnol.