Julian March

Ascoli emphasized the Augustan partition of Roman Italy at the beginning of the Empire, when Venetia et Histria was Regio X (the Tenth Region).

In an 1863 newspaper article,[4] Ascoli focused on a wide geographical area north and east of Venice which was under Austrian rule; he called it Triveneto ("the three Venetian regions").

[9] Beginning in the early Middle Ages, two main political powers shaped the region: the Republic of Venice and the Habsburg (the dukes and, later, archdukes of Austria).

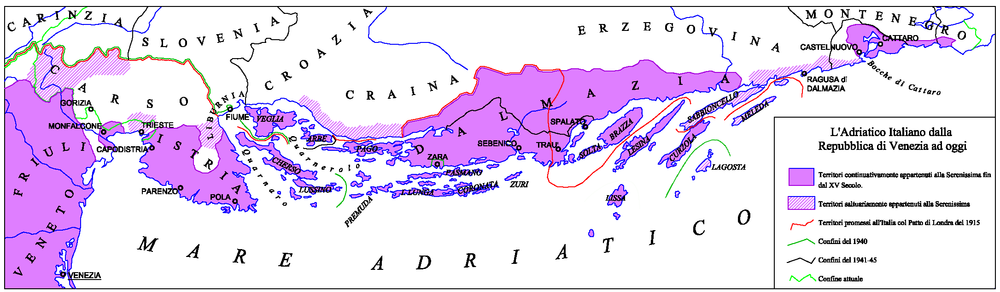

During the 11th century, Venice began building an overseas empire (Stato da Màr) to establish and protect its commercial routes in the Adriatic and southeastern Mediterranean Seas.

Coastal areas of Istria and Dalmazia were key parts of these routes[a] since Pietro II Orseolo, the Doge of Venice, established Venetian rule in the high and middle Adriatic around 1000.

The Republic of Venice began expanding toward the Italian interior (Stato da Tera) in 1420,[10] acquiring the Patriarchate of Aquileia (which included a portion of modern Friuli—the present-day provinces of Pordenone and Udine—and part of internal Istria).

The Habsburg held the March of Carniola, roughly corresponding to the central Carniolan region of present-day Slovenia (part of their holdings in Inner Austria), since 1335.

During the next two centuries, they gained control of the Istrian cities of Pazin and Rijeka-Fiume, the port of Trieste (with Duino), Gradisca and Gorizia (with its county in Friuli).

The Habsburgs gained Venetian lands on the Istrian Peninsula and the Quarnero (Kvarner) islands, expanded their holdings in 1813 with Napoleon's defeats and the dissolution of the French Illyrian provinces.

This was established as a crown land (Kronland) of the Austrian Empire, consisting of three regions: the Istrian peninsula, Gorizia and Gradisca, and the city of Trieste.

[12] During the meeting of the Council of Ministers of 12 November 1866, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria outlined a wide-ranging project aimed at the Germanization or Slavization of the areas of the empire with an Italian presence:[13] His Majesty expressed the precise order that action be taken decisively against the influence of the Italian elements still present in some regions of the Crown and, appropriately occupying the posts of public, judicial, masters employees as well as with the influence of the press, work in South Tyrol, Dalmatia and Littoral for the Germanization and Slavization of these territories according to the circumstances, with energy and without any regard.

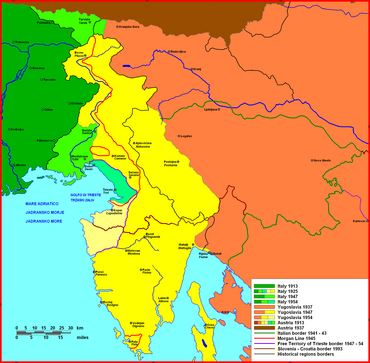

[17] The Kingdom of Italy annexed the region after World War I according to the Treaty of London and later Treaty of Rapallo, comprising most of the former Austrian Littoral (Gorizia and Gradisca, Trieste and Istria), south-western portions of the former Duchy of Carniola, and the current Italian municipalities of Tarvisio, Pontebba and Malborghetto Valbruna which had been Carinthian (aside from Fusine in Valromana in eastern Tarvisio, which had been part of Carniola).

[18] Rijeka-Fiume, which had enjoyed special status within the Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen (the Hungarian part of Austria-Hungary), became an independent city-state in the Treaty of Rapallo: the Free State of Fiume.

Fascist persecution, "centralising, oppressive and dedicated to the forcible Italianisation of the minorities",[19] caused the emigration of about 105,000[6] Slovenes and Croats from the Julian March—around 70,000 to Yugoslavia and 30,000 to Argentina.

TIGR co-ordinated Slovene resistance against Fascist Italy until it was dismantled by the secret police in 1941, and some former members joined the Yugoslav Partisans.

The German Army began to occupy the region and encountered severe resistance from Yugoslav partisans, particularly in the lower Vipava Valley and the Alps.

The Western allies adopted the term "Julian March" as the name for the territories which were contested between Italy and the People's Federal Republic of Yugoslavia between 1945 and 1947.

Tensions continued, and in 1954 the territory was abolished and divided between Italy (which received the city of Trieste and its surroundings) and Yugoslavia,[22] under the terms of the London Memorandum.

The Treaty of Osimo was signed on 10 November 1975 by the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Italian Republic in Osimo, Italy, to definitively divide the Free Territory of Trieste between the two states: the port city of Trieste with a narrow coastal strip to the north-west (Zone A) was given to Italy; a portion of the north-western part of the Istrian peninsula (Zone B) was given to Yugoslavia.

Other ethnic groups included Istro-Romanians in eastern Istria, Carinthian Germans in the Canale Valley and smaller German- and Hungarian-speaking communities in larger urban centres, primarily members of the former Austro-Hungarian elite.

The Italian-speaking elite dominated the governments of Trieste and Istria under Austro-Hungarian rule, although they were increasingly challenged by Slovene and Croatian political movements.

Venetian was also a strong presence on Istria's Cres-Lošinj archipelago and in the peninsula's eastern and interior towns such as Motovun, Labin, Plomin and, to a lesser extent, Buzet and Pazin.

Slovene was spoken in the north-eastern and southern parts of Gorizia and Gradisca (by about 60 percent of the population), in northern Istria and in the Inner Carniolan areas annexed by Italy in 1920 (Postojna, Vipava, Ilirska Bistrica and Idrija).

Slavia Friulana – Beneška Slovenija, the community living since the eighth century in small towns (such as Resia) in the valleys of the Natisone, Torre and Judrio Rivers in Friuli, has been part of Italy since 1866.

Most of the German speakers would speak Italian, Slovene or Croatian on social and public occasions, depending on their political and ethnic preferences and location.