Italian Australians

[citation needed] Nevertheless, they did not come from the landless, poverty-stricken agricultural working class but from rural families with at least sufficient means to pay their fare to Australia.

[citation needed] Therefore, other overseas destinations such as the United States and the Latin American countries proved much more attractive, thus allowing the establishment of migration patterns more quickly and drawing far greater numbers.

The drain on the labour supply occasioned by the gold rush caused Australia to also seek workmen from Europe for land use and the development of cultivation, both in New South Wales and Queensland.

[citation needed] While Italians in Australia were less than 2,000, they tended to increase, because they were attracted by the easy possibility to settle in areas capable of intense agricultural exploitation.

[citation needed] In this regard, it must be borne in mind again that in the early 1880s Italy was facing a strong economic crisis, which was going to push a hundred thousand Italians to seek a better life abroad.

[citation needed] In addition, even Australian travellers, like Randolph Bedford, who visited Italy in the 1870s and 1880s, admitted the convenience of having a larger intake of Italian workers into Australia.

As the job opportunities attracted so many British people to the colonies to be employed in agriculture, certainly the Italian peasant, accustomed to be a hard-worker, "frugal and sober", would be a very good immigrant for the Australia soil.

Many Italian immigrants had extensive knowledge of Mediterranean-style farming techniques, which were better suited to cultivating Australia's harsh interior than the Northern-European methods in use previous to their arrival.

[citation needed] They were the survivors from Marquis de Ray's ill-fated attempt at founding a colony, Nouvelle France, in New Ireland, which later became part of Germany's New Guinea Protectorate.

In 1883, a commercial Treaty between the United Kingdom and Italy was signed, allowing Italian subjects freedom of entry, travel and residence, and the rights to acquire and own property and to carry on business activities.

The deciding factor in the whole matter was the plight of the sugar industry: docile gang labour was essential, and the "frugal" Italian peasants were perfectly suited for such employment.

They slowly acquired a large number of sugar-cane plantations and gradually set up thriving Italian communities in north Queensland around the towns of Ayr and Innisfail.

The gold rush of the early 1890s in Western Australia and the subsequent labour disputes at the mines had belatedly attracted Italians in large number, both from Victoria and Italy itself.

The Italian Geographical Society (Societa' Geografica Italiana) reported as follows about the few Italian settlements in Australia: Nella maggior parte dei casi l'operaio (italiano) vive sotto la tenda, così chiunque non sia dedito all'ubriachezza (cosa troppo comune in questi paesi, ma non fra i nostri connazionali) può facilmente risparmiare la metà del suo salario.

In Western Australia, fishing was next in popularity, followed by the usual urban pursuits now associated with Italians of peasant origin, such as market gardening, the keeping of restaurants and wine shops and the sale of fruit and vegetables.

Fuelled both by the British-European feeling of loss of supremacy and the fears of the Australian Labor Party in working sectors where labourers were not exclusively Anglo-Celtic, anti-Italian sentiments gathered momentum in the United States in the early 1900s, in the wake of Italian mass migration.

[citation needed] Although his report on soil fertility, quality of cattle to graze, transport and accommodation for the Italian farmers was extremely positive and enthusiastic, the settlement scheme was not carried out.

With respect to this attitude, MacDonald wrote: "Italian immigration became the largest non-British movement after the entry of Melanesians and Asians was stopped by the new federal government in 1902.

Gradually, the arrays of migrants became formed also by a minor component of political opponents to Fascism, generally peasants of the northern Italian regions, who chose Australia as their destination.

In his study on Italian migration to South Australia, O'Connor even reports on the presence, in 1926, in Adelaide of a dangerous anarchist "subversive" from the village of Capoliveri, in the Tuscan Island of Elba, one Giacomo Argenti.

As observed by Bertola in his study of the riots, racism towards Italians lay in "their apparent willingness to be used in efforts to drive down wages and conditions, and their inability to transcend the boundaries that separated them from the host culture".

[...] Gli Italiani formarono quel fronte unico di resistenza che va considerato una delle più belle vittorie del fascismo in terra straniera.

Between 1940 and 1945, most of those who had not been naturalised before the war's outbreak were considered "enemy aliens", and therefore either interned or subjected to close watch, with respect to personal movements and area of employment.

But while the act of naturalization may have been an irrevocable step which in turn provided an incentive to become socially and culturally assimilated, field investigations show clearly that Italians retained many traits, particularly within the circle of the home, which were not "Australian".

[12]Conversely, after the war experience, the Australian government embarked on the 'Populate or Perish' program, aimed to increase the population of the country for strategically important economic and military reasons.

The war had occasioned a shift in migration patterns, pressing the need to place a large number of people who could not return to their own countries for a wide range of reasons.

This circumstance is a consequence of the migration patterns followed by Italians in the earlier stage of their settlement in Queensland, during the 1910s, 1920s and 1930s, when the sugarcane industry and its related possibility of quick earnings attracted more "temporary" migrants in the countryside.

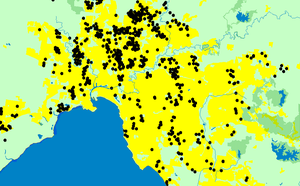

The way in which a population "subgroup" is distributed across an area is of importance because not only can it tell us a great deal about the pattern of life of that group, but it is also crucial in any planning of service delivering to such a community.

Over two-thirds all Italians were employed either in mines or in the mine-related woodcutting industry (respectively about 400 and 800), both in the gold districts of Gwalia, Day Down, Coolgardie and Cue, and the forests of Karrawong and Lakeside.

During these two decades, Italian migrants to Australia continued to come from the north and central mountain areas of Italy, thus following a pattern of "temporary" migration that pushed them to look for jobs with potential quick remuneration, as mining and woodcutting could offer.