Italian governorate of Montenegro

[11] In May 1940, as a means of opposing the government, the Montenegrin branch of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (Serbo-Croatian: Komunistička partija Jugoslavije, KPJ) advocated that Royal Yugoslav Army reservists demobilise, refuse military discipline, and even desert.

[12] In April 1941, as part of the German-led Axis invasion of Yugoslavia, the Zeta Banovina was attacked, by Germans coming from Bosnia and Herzegovina and Italians from Albania.

[15] On 28 April, Count Serafino Mazzolini was appointed the civil commissioner for Montenegro,[13] but subordinated to the High Command of the Italian Armed Forces in Albania (known as Superalba).

Italian flags were distributed and flown, photographs of Benito Mussolini and King of Italy were displayed in public offices, and the Fascist Roman salute was made compulsory.

On 19 June, Mazzolini was appointed as "High Commissioner", responsible to the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for matters of civil administration in the occupied territory.

The Italians were relying heavily on information provided by a group of émigré loyalists of the deposed House of Petrović-Njegoš, that had ruled Montenegro for centuries prior to the union with the Kingdom of Serbia in 1918.

Popović sought a fully independent Montenegro, but was willing to consider a separate entity within a federal Yugoslavia depending on the outcome of the war, and his group included some members of the Montenegrin Federalist Party.

These grievances mainly related to the expulsion of Montenegrin people from the Kosovo region[8] and Bačka and Baranya, as well as the influx of refugees from other parts of Yugoslavia and those fleeing the Ustaše terror in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

[24] In early July 1941, a senior Montenegrin member of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the KPJ, Milovan Đilas, arrived in Montenegro from Belgrade to start the communist struggle against the occupying forces.

[17] When the members of the National Assembly realised that the declaration would result in a union of the Italian monarchy with Montenegro, and offered no real independence to the new state, nearly all of the delegates returned to their towns and villages.

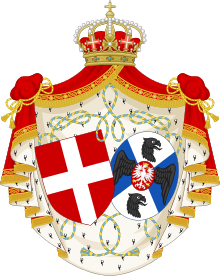

[20] No member of the Petrović-Njegoš dynasty was willing to accept the throne, so the National Assembly decided to establish a "Regency" under the nominal rule of Italian King Victor Emmanuel III.

The event that triggered the uprising was the proclamation on the previous day of a restored Kingdom of Montenegro headed by an Italian regent and led by Montenegrin separatist Drljević and the "Greens".

[27][29] The insurgents also included large numbers of Serb nationalists known as "Whites" (bjelaši), who "stood for close ties to Serbia",[29] and former Yugoslav Army officers, some of whom had recently been released from prisoner-of-war camps.

Amidst the worst of the fighting during the successful attack he led on Berane, then-Captain Pavle Đurišić distinguished himself,[32][33] and emerged as one of the main commanders of the uprising.

Unlike the Partisans who had strong central direction from the outset, during these early stages the nationalists in Montenegro had little or no contact with the headquarters of Draža Mihailović, who would eventually become the titular leader of the Chetnik movement in Yugoslavia.

[48][49][50] Despite his possession of these instructions, Đurišić initially had very little influence on the non-communist elements of the Montenegrin resistance and was unable to develop an effective strategy against the Italians or Partisans in the first few months after his return to Montenegro.

[51] The Partisans occupied Kolašin in January and February 1942, and turned against all real and potential opposition, killing about 300 of the population and throwing their mangled corpses into pits they called the "dogs' cemetery".

[29] In early February, Bajo Stanišić withdrew two units under his command from the insurgent front-line around Danilovgrad in central Montenegro, allowing the besieged Italians to break out and defeat the Partisans.

In late February or early March, Mihailović sent one of his agents to join Stanišić, who began to coordinate his activities with the other significant Chetnik leaders in Montenegro.

[57] On 9 March, a large group of former Royal Yugoslav Army officers met at Cetinje and elected Blažo Đukanović to command all nationalist forces in Montenegro.

[57] On 24 July 1942, a comprehensive agreement was reached between Đukanović and Biroli, which expanded the areas covered and ensured that the Chetniks in Montenegro could bear the brunt of the fighting against the Partisans.

Specifically, the Đukanović-Biroli agreement stated that "the Chetniks were to continue uncompromising struggle against the Communists and were to cooperate with the Italian authorities in the restoration and maintenance of law and order".

It mandated the creation of three "flying detachments" of 1,500 men each, commanded by Đurišić, Stanišić and the separatist leader Popović, and covered pay, rations, arms and support for their families.

Popović, the Montenegrin separatist leader and commander of the third "flying detachment", had been collaborating with the Italians from the time of the invasion, and continued to do so, having reached a fragile understanding with the Chetniks during the first half of 1942.

[61] The conference was dominated by Đurišić and its resolutions expressed extremism and intolerance, as well as an agenda which focused on restoring the pre-war status quo in Yugoslavia implemented in its initial stages by a Chetnik dictatorship.

Others surrendered themselves, arms, ammunition and equipment to Croatian forces or to the Partisans, simply disintegrated, or reached Italy on foot via Trieste or by ship across the Adriatic.

At its core was a small area running south into the Sandžak from Berane, including the towns of Prijepolje, Bijelo Polje, Sjenica, and some villages around Tutin and Rožaje, incorporating a Muslim minority numbering 80,000.

The Bay of Kotor was annexed as part of the Italian Governorate of Dalmatia, and the border between the Independent State of Croatia and Montenegro followed the Lim in the Drina region as far as Hum, then via Dobricevo to the Adriatic.

Kosovska Mitrovica and the Ibar River valley were incorporated into the German-occupied territory of Serbia, including the towns of Kukavica, Podujevo and Medveđa, and the Trepča zinc mines.

The Cacciatori delle Alpi division was re-deployed to the NDH in September 1941, but the rest remained as a strengthened occupation force until December 1941, during which they fought off local attacks.