Italo-Turkish War

At the Congress of Berlin in 1878, France and the United Kingdom had agreed to the French occupation of Tunisia and British control over Cyprus respectively, which were both parts of the declining Ottoman state.

[19] The agreement, negotiated by Italian Foreign Minister Giulio Prinetti and French Ambassador Camille Barrère, ended the historic rivalry between both nations for control of North Africa.

Those measures were intended to loosen Italian commitment to the Triple Alliance and thereby weaken Germany, which France and Britain viewed as their main rival in Europe.

Following the Anglo-Russian Convention and the establishment of the Triple Entente, Tsar Nicholas II and King Victor Emmanuel III made the 1909 Racconigi Bargain in which Russia acknowledged Italy's interest in Tripoli and Cyrenaica in return for Italian support for Russian control of the Bosphorus.

Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti rejected nationalist calls for conflict over Ottoman Albania, which was seen as a possible colonial project, as late as the summer of 1911.

On 19 September, Grey instructed Permanent Under-Secretary of State Sir Arthur Nicolson, 1st Baron Carnock that Britain and France should not interfere with Italy's designs on Libya.

Giolitti and Foreign Minister Antonino Paternò Castello agreed on 14 September to launch a military campaign "before the Austrian and German governments [were aware] of it".

Germany was then actively attempting to mediate between Rome and Constantinople, and Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Alois Lexa von Aehrenthal repeatedly warned Italy that military action in Libya would threaten the integrity of the Ottoman Empire and create a crisis in the Eastern Question, which would destabilise the Balkan Peninsula and the European balance of power.

[citation needed] An ultimatum was presented to the Ottoman government, led by the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), on the night of 26–27 September 1911.

A considerable number of Italians were living within the Ottoman Empire, mostly inhabiting Istanbul, Izmir, and Thessaloniki, dealing with trade and industry.

Depending on the mutual friendly relations, the Ottoman Government had sent their Libyan battalions to Yemen in order to suppress local rebellions, leaving only the military police in Libya.

Having no prior military experiences and lacking adequate planning for amphibious invasions, the Italian armies poured onto the coasts of Libya, facing numerous problems during their landings and deployments.

A week later, Sottotenente Giulio Gavotti dropped four grenades on Tajura (Arabic: تاجوراء Tājūrā’, or Tajoura) and Ain Zara in the first aerial bombing in history.

[38] The Libyans and Turks, estimated at 15,000, made frequent attacks day and night on the strongly-entrenched Italian garrison in the southern suburbs of Benghazi.

[38] The cost of the war was defrayed chiefly by voluntary offerings from Muslims; men, weapons, ammunition and all kinds of other supplies were constantly sent across to the Egyptian and Tunisian frontiers, not withstanding their neutrality.

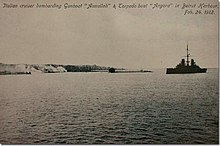

[43] In January 1912, the Italian cruiser Piemonte, with the Soldato class destroyers Artigliere and Garibaldino, sank seven Ottoman gunboats (Ayintab, Bafra, Gökcedag, Kastamonu, Muha, Ordu and Refahiye) and a yacht (Sipka) in the Battle of Kunfuda Bay.

Although Italy could extend its control to almost all of the 2,000 km of the Libyan coast between April and early August 1912, its ground forces could not venture beyond the protection of the navy's guns and so were limited to a thin coastal strip.

In the summer of 1912, Italy began operations against the Ottoman possessions in the Aegean Sea with the approval of the other powers, which were eager to end a war that was lasting much longer than expected.

Italy occupied twelve islands in the sea, comprising the Ottoman province of Rhodes, which then became known as the Dodecanese, but that raised the discontent of Austria-Hungary, which feared that it could fuel the irredentism of nations such as Serbia and Greece and cause imbalance in the already-fragile situation in the Balkan area.

[46] Many local Libyans joined forces with the Ottomans because of their common faith against the "Christian invaders" and started bloody guerrilla warfare.

[47] This massacre occurred, at least in part, reportedly due to the rape and sexual assault of Libyan and Turkish women by the Italian troops.

[48] Nevertheless, as a consequence, on the next day the 1911 Tripoli massacre had Italian troops systematically murder thousands of civilians by moving through local homes and gardens one by one, including by setting fire to a mosque with 100 refugees inside.

Turkey was in no position to reoccupy the islands while its main armies were engaged in a bitter struggle to preserve its remaining territories in the Balkans.

[53] After the withdrawal of the Ottoman army the Italians could easily extend their occupation of the country, seizing East Tripolitania, Ghadames, the Djebel and Fezzan with Murzuk during 1913.

[54] The outbreak of the First World War with the necessity to bring back the troops to Italy, the proclamation of the Jihad by the Ottomans and the uprising of the Libyans in Tripolitania forced the Italians to abandon all occupied territory and to entrench themselves in Tripoli, Derna, and on the coast of Cyrenaica.

[54] The Italian control over much of the interior of Libya remained ineffective until the late 1920s when forces under the Generals Pietro Badoglio and Rodolfo Graziani waged bloody pacification campaigns.

"[56] Unlike the British-controlled Egypt, the Ottoman Tripolitania vilayet, which made up modern-day Libya, was core territory of the Empire, like that of the Balkans.

The Italo-Turkish War illustrated to the French and British governments that Italy was more valuable to them inside the Triple Alliance than being formally allied with the Entente.

[citation needed] In Italy itself, massive funerals for fallen heroes brought the Catholic Church closer to the government from which it had long been alienated.

According to the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres, which was never ratified, Italy was supposed to cede all of the islands except Rhodes to Greece in exchange for a vast Italian zone of influence in southwest Anatolia.

(from Italian weekly La Domenica del Corriere , 26 May – 2 June 1912).