JP Miller

He served in the Navy in the South Pacific, primarily as a gunnery officer, seeing combat first aboard the heavy cruiser USS Chester – torpedoed early in the war by a Japanese submarine.

Aboard the aircraft carrier USS Cabot, he learned deep sea diving and adopted the name JP Miller (minus periods after the initials) after receiving orders in that format by U.S. Navy addressing machines.

After World War II, he studied writing and acting at the Yale Drama School and then went to Houston, where he sold real estate and Coleman furnaces.

However, Miller received the most acclaim for Days of Wine and Roses, which was prompted by his notion to dramatize Alcoholics Anonymous meetings (which were something of a mystery in the early 1950s).

Presented live with tape inserts on CBS, the television production, starring Cliff Robertson, Piper Laurie, Charles Bickford and Malcolm Atterbury, was a powerful slice of life probe into the nature of alcoholism.

Her interpretation of the young wife just a shade this side of delirium tremens—the flighty dancing around the room, her weakness of character and moments of anxiety and her charm when she was sober—was a superlative accomplishment.

[2]Miller's Days of Wine and Roses received favorable critical attention and was nominated for an Emmy in the category "Best Writing of a Single Dramatic Program – One Hour or Longer."

Playhouse 90 producer Martin Manulis decided the material would be ideal as a motion picture, but some critics observed that the film, directed by Blake Edwards, lacked the impact of the original television production.

In an article written for DVD Journal, critic D. K. Holm noted alterations from the original: When the opportunity arose to make a film version of J. P. Miller's powerful TV drama Days of Wine and Roses, actor Jack Lemmon suggested that the studio hire Blake Edwards (according to Edwards, that is) rather than the Playhouse 90 production's original director, John Frankenheimer.

Unfortunately, Edwards, who is kind of a combination of George Stevens (comedy director turned prestige filmmaker) and Vincente Minnelli (excitable content with no distinctive visual style), tilted the original material towards schmaltz, from the comically lush theme-song by Henry Mancini to the exaggerated binge scenes.

[3]Miller's theatrical films include The Rabbit Trap (1959), The Young Savages (1961, with Edward Anhalt), Days of Wine and Roses (1962) and Behold a Pale Horse (1964).

In what was the first use of a hologram on a book cover, the Skook was sketched by Miller and then sculpted by Eidetic Images, Inc., an American Bank Note subsidiary.

The prose adaptation was by David Westheimer, a mainstream novelist of some note (Von Ryan's Express, among others), who was also a friend of Miller's; but he only received by-line credit on the book's first iteration, a movie tie-in edition featuring cover stills from the film.

At the age of 81, Miller died of pneumonia at the Hunterdon Medical Center in Flemington, New Jersey, having completed a first draft of his World War II memoirs, A Ship Without a Shore.

In 2003, Rachel Wood directed the New York stage premiere of Days of Wine and Roses, an off-Broadway production by the Boomerang Theatre Company.

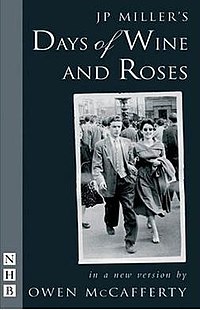

In 2005, the Northern Irish writer Owen McCafferty relocated Days of Wine and Roses to London in the 1960s, reworking it to focus on a young couple just arrived from Belfast.

The playwright P. J. Gibson, who became a Miller student when she was 14, has written poetry, short stories and 22 plays, including Long Time Since Yesterday.