Jack the Ripper

Five victims—Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes and Mary Jane Kelly—are known as the "canonical five" and their murders between 31 August and 9 November 1888 are often considered the most likely to be linked.

Nichols had last been seen alive approximately one hour before the discovery of her body by a Mrs. Emily Holland, with whom she had previously shared a bed at a common lodging-house in Thrawl Street, Spitalfields, walking in the direction of Whitechapel Road.

[45] The cause of death was a single clear-cut incision, measuring six inches across her neck which had severed her left carotid artery and her trachea before terminating beneath her right jaw.

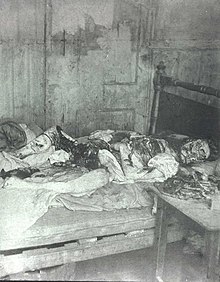

[63][64] The extensively mutilated and disembowelled body of Mary Jane Kelly was discovered lying on the bed in the single room where she lived at 13 Miller's Court, off Dorset Street, Spitalfields, at 10:45 a.m. on Friday 9 November 1888.

[69] Multiple ashes found within the fireplace at 13 Miller's Court suggested Kelly's murderer had burned several combustible items to illuminate the single room as he mutilated her body.

[74] In 1894, Sir Melville Macnaghten, Assistant Chief Constable of the Metropolitan Police Service and Head of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), wrote a report that stated: "the Whitechapel murderer had 5 victims—& 5 victims only".

[75] Similarly, the canonical five victims were linked together in a letter written by police surgeon Thomas Bond to Robert Anderson, head of the London CID, on 10 November 1888.

[77] Authors Stewart P. Evans and Donald Rumbelow argue that the canonical five is a "Ripper myth" and that three cases (Nichols, Chapman, and Eddowes) can be definitely linked to the same perpetrator, but that less certainty exists as to whether Stride and Kelly were also murdered by the same person.

[17] Percy Clark, assistant to the examining pathologist George Bagster Phillips, linked only three of the murders and thought that the others were perpetrated by "weak-minded individual[s] ... induced to emulate the crime".

[80] Mary Jane Kelly is generally considered to be the Ripper's final victim, and it is assumed that the crimes ended because of the culprit's death, imprisonment, institutionalisation, or emigration.

[95] At 2:15 a.m. on 13 February 1891, PC Ernest Thompson discovered a 31-year-old prostitute named Frances Coles lying beneath a railway arch at Swallow Gardens, Whitechapel.

[102] "Fairy Fay" was a nickname given to an unidentified[103] woman whose body was allegedly found in a doorway close to Commercial Road on 26 December 1887[104] "after a stake had been thrust through her abdomen",[105][106] but there were no recorded murders in Whitechapel at or around Christmas 1887.

[102][103] A 38-year-old widow named Annie Millwood was admitted to the Whitechapel Workhouse Infirmary with numerous stab wounds to her legs and lower torso on 25 February 1888,[109] informing staff she had been attacked with a clasp knife by an unknown man.

[111] Another suspected precanonical victim was a young dressmaker named Ada Wilson,[112] who reportedly survived being stabbed twice in the neck with a clasp knife[113] upon the doorstep of her home in Bow on 28 March 1888 by a man who had demanded money from her.

[133] The overall direction of the murder enquiries was hampered by the fact that the newly appointed head of the CID, Assistant Commissioner Robert Anderson, was on leave in Switzerland between 7 September and 6 October, during the time when Chapman, Stride, and Eddowes were killed.

[134] This prompted Colonel Sir Charles Warren, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, to appoint Chief Inspector Donald Swanson to coordinate the enquiry from Scotland Yard.

[136] A surviving note from Major Henry Smith, Acting Commissioner of the City Police, indicates that the alibis of local butchers and slaughterers were investigated, with the result that they were eliminated from the inquiry.

They patrolled the streets looking for suspicious characters, partly because of dissatisfaction with the failure of police to apprehend the perpetrator, and also because some members were concerned that the murders were affecting businesses in the area.

[146] At the end of October, Robert Anderson asked police surgeon Thomas Bond to give his opinion on the extent of the murderer's surgical skill and knowledge.

[76] In his opinion, the killer must have been a man of solitary habits, subject to "periodical attacks of homicidal and erotic mania", with the character of the mutilations possibly indicating "satyriasis".

[154] The term "ripperology" was coined to describe the study and analysis of the Ripper case in an effort to determine his identity, and the murders have inspired numerous works of fiction.

[161] DNA analysis has attempted to tie Aaron Kosminski (a Whitechapel barber) to crime scene evidence and Walter Sickert to letters (possibly hoaxes) claiming to be from the Ripper.

The handwriting was similar to the "Dear Boss" letter,[185] and mentioned the canonical murders committed on 30 September, which the author refers to by writing "double event this time".

[194] Scotland Yard published facsimiles of the "Dear Boss" letter and the postcard on 3 October, in the ultimately vain hope that a member of the public would recognise the handwriting.

[195] Charles Warren explained in a letter to Godfrey Lushington, Permanent Under-Secretary of State for the Home Department: "I think the whole thing a hoax but of course we are bound to try & ascertain the writer in any case.

[199][n 1] A journalist named Fred Best reportedly confessed in 1931 that he and a colleague at The Star had written the letters signed "Jack the Ripper" to heighten interest in the murders and "keep the business alive".

[205] These mushroomed in the later Victorian era to include mass-circulation newspapers costing as little as a halfpenny, along with popular magazines such as The Illustrated Police News which made the Ripper the beneficiary of previously unparalleled publicity.

Sensational press reports combined with the fact that no one was ever convicted of the murders have confused scholarly analysis and created a legend that casts a shadow over later serial killers.

[220] The nature of the Ripper murders and the impoverished lifestyle of the victims[221] drew attention to the poor living conditions in the East End[222] and galvanised public opinion against the overcrowded, insanitary slums.

In the 1920s and 1930s, he was depicted in film dressed in everyday clothes as a man with a hidden secret, preying on his unsuspecting victims; atmosphere and evil were suggested through lighting effects and shadowplay.