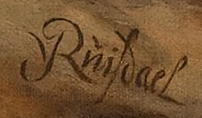

Jacob van Ruisdael

The number of painters in the family, and the multiple spellings of the Van Ruisdael name, have hampered attempts to document his life and attribute his works.

[10] Archival records of the 17th century show the name "Jacobus Ruijsdael" on a list of Amsterdam doctors, albeit crossed out, with the added remark that he earned his medical degree on 15 October 1676 in Caen, northern France.

[31][32] His uncle Salomon van Ruysdael belonged to the Young Flemish subgroup of the Mennonite congregation, one of several types of Anabaptists in Haarlem, and it is probable that Ruisdael's father was also a member there.

[44]Ruisdael's work from c. 1646 to the early 1650s, when he was living in Haarlem, is characterised by simple motifs and careful and laborious study of nature: dunes, woods, and atmospheric effects.

By applying heavier paint than his predecessors, Ruisdael gave his foliage a rich quality, conveying a sense of sap flowing through branches and leaves.

[46] His early sketches introduce motifs that would return in all his work: a sense of spaciousness and luminosity, and an airy atmosphere achieved through pointillist-like touches of chalk.

It breaks with the classic Dutch tradition of depicting broad views of dunes that include houses and trees flanked by distant vistas.

[47] The resulting heroic effect is enhanced by the large size of the canvas, "so unexpected in the work of an inexperienced painter" according to Irina Sokolova, curator at the Hermitage Museum.

[53] The etching expert Georges Duplessis singled out Grainfield at the Edge of a Wood and The Travellers as unrivalled illustrations of Ruisdael's genius.

Significantly, Ruisdael made numerous changes to the castle's setting (it is actually on an unimposing low hill) culminating in a 1653 version which shows it on a wooded mountain.

There is no record that Ruisdael made any trip to Scandinavia, although fellow Haarlem painter Allart van Everdingen had travelled there in 1644 and had popularised the subgenre.

[67] In this period Ruisdael started painting coastal scenes and sea-pieces, influenced by Simon de Vlieger and Jan Porcellis.

The art historian Wolfgang Stechow identified thirteen themes within the Dutch Golden Age landscape genre, and Ruisdael's work encompasses all but two of them, excelling at most: forests, rivers, dunes and country roads, panoramas, imaginary landscapes, Scandinavian waterfalls, marines, beachscapes, winter scenes, town views, and nocturnes.

[74] The painting's enduring popularity is evidenced by card sales in the Rijksmuseum, with the Windmill ranking third after Rembrandt's Night Watch and Vermeer's View of Delft.

[75] Various panoramic views of the Haarlem skyline and its bleaching grounds appear during this stage, a specific genre called Haerlempjes,[22] with the clouds creating various gradations of alternating bands of light and shadow towards the horizon.

[77][78] Figures are introduced sparingly into Ruisdael's compositions, and are by this period rarely from his own hand[J] but executed by various artists, including his pupil Meindert Hobbema, Nicolaes Berchem, Adriaen van de Velde, Philips Wouwerman, Jan Vonck, Thomas de Keyser, Gerard van Battum and Jan Lingelbach.

[98] Similarly, Piet Mondrian's early abstract compositions the eventually led to the founding of De Stijl have been traced back to Ruisdael's panoramas.

The first account, in 1718, is from Houbraken, who waxed lyrical over the technical mastery which allowed Ruisdael to realistically depict falling water and the sea.

In 1801, Henry Fuseli, professor at the Royal Academy, expressed his contempt for the entire Dutch School of Landscape, dismissing it as no more than a "transcript of the spot", a mere "enumeration of hill and dale, clumps of trees".

[92] Around the same time in Germany, the writer, statesman and scientist Johann Wolfgang von Goethe lauded Ruisdael as a thinking artist, even a poet,[101] saying "he demonstrates remarkable skill in locating the exact point at which the creative faculty comes into contact with a lucid mind".

[102] John Ruskin however, in 1860, raged against Ruisdael and other Dutch Golden Age landscapists, calling their landscapes places where "we lose not only all faith in religion but all remembrance of it".

Januszczak does not consider Ruisdael the greatest landscape artist of all time, but is especially impressed by his works as a teenager: "a prodigy whom we should rank at number 8 or 9 on the Mozart scale".

[100] At the other end is Franz Theodor Kugler who sees meaning in almost everything: "They all display the silent power of Nature, who opposes with her mighty hand the petty activity of man, and with a solemn warning as it were, repels his encroachments".

[113] In the middle of the spectrum are scholars such as E. John Walford, who sees the works as "not so much bearers of narrative or emblematic meanings but rather as images reflecting the fact that the visible world was essentially perceived as manifesting inherent spiritual significance".

[117] Slive, sensible scholar that he is, is more reluctant to read too much into the work, but does put The Windmill in its contemporary religious context of man's dependence on the "spirit of the Lord for life".

[118] With regards to interpreting Ruisdael's Scandinavian paintings, he says "My own view is that it strains credulity to the breaking point to propose that he himself conceived of all his depictions of waterfalls, torrents and rushing streams and dead trees as visual sermons on the themes of transcience and vanitas".

[125] Of his surviving drawings, 140 in total,[126] the Rijksmuseum,[127] the Teylers Museum in Haarlem,[128] Dresden's Kupferstich-Kabinett,[15] and the Hermitage each hold significant collections.

[130] According to some, Ruisdael and his art should not be considered apart from the context of the incredible wealth and significant changes to the land that occurred during the Dutch Golden Age.

In his study on 17th-century Dutch art and culture, Simon Schama remarks that "it can never be overemphasized that the period between 1550 and 1650, when the political identity of an independent Netherlands nation was being established, was also a time of dramatic physical alteration of its landscape".

[134] As well, ordinary middle class Dutch people began buying art for the first time, creating a high demand for paintings of all kinds.