Jacques Chenevière

[2] The award-winning author, whose father Adolphe Chenevière (1855–1917) was a critically acclaimed man of letters as well, wrote in French and became most famous for his works of psychological fiction.

While two sons of Arthur and Susanne-Firmine became bankers as well and their daughter married the founder of the Union Bank (later UBS),[12] their brother Adolphe did not pursue his career as an advocate but instead became a novelist and essayist.

The four siblings thus embodied the development of their Patrician class, which «turned to banking and philanthropic activities at the end of the 19th century, after losing control of the major public offices in Geneva.»[13]Adolphe moved to Paris around 1880, where he worked as a literary critic at the prestigious Revue des Deux Mondes,[14] which is today the oldest still existing cultural magazine in Europe.

[17] The critic Charlotte König-von Dach argued that Jacques' mother gave him «the sparkling verve, the luster, and the mobility of poetic intuition as gifts from the Midi de la France, in contrast to the heavier calvinist-protestant blood of Geneva».

[20] At a young age already he thus had personal encounters with luminaries like novelist Marcel Proust (1871–1922), the composer Reynaldo Hahn (1874–1947) and the stage actress Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923).

[22] Shortly afterwards, Chenevière was commissioned by the French composer Louis Aubert (1877–1968) to write the lyrics for the Opéra-comique La forêt bleue («The blue forest»), which premiered in Boston at the end of 1911.

Shortly after the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the ICRC under its president Gustave Ador established the International Prisoners-of-War Agency (IPWA) to trace POWs and to re-establish communications with their respective families.

[31] The Austrian writer and pacifist Stefan Zweig described the situation during those early days at the agency as follows:«Hardly had the first blows been struck when cries of anguish from all lands began to be heard in Switzerland.

The connection between the Chenevières came through family tradition and bonds as well: Adolphe's younger brother Edmond (1862–1932) was married to a daughter of the Milanese banker Charles Brot, who played a role when the ICRC was founded.

[2] Under those conditions, Chenevière quickly rose to become the co-director of the IPWA department which was responsible for the Triple Entente of the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

Most notably, he joined the child psychologist Édouard Claparède (1873–1940) and his brother-in-law Auguste de Morsier (1864–1923), a prominent proponent of women's suffrage, to collect funds for Jaques-Dalcroze who was thus able to found his own institute in October 1915.

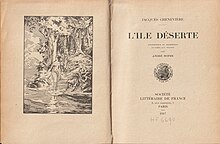

The plot about a Parisian man and a woman who get stranded on a polynesian atoll and gradually overcome their mutual resentments, was a scandalous affront for large swaths of the Calvinist-puritan upper-class.

With his childhood friend de Traz,[22] who like him was born in Paris as the son of a Swiss father and a French mother,[45] he especially promoted the revival of literary exchanges between the German- and French-speaking worlds.

[2] When the ICRC in March 1936 received reports from its delegate Marcel Junod, a medical doctor, about the Italian use of chemical weapons in Korem, ICRC-president Max Huber travelled to Rome with Chenevière and Carl Jacob Burckhardt, who was a professor of history at the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva and a leading ICRC-member as well.

During the internal debate which followed upon their return to Geneva, Chenevière joined the group of lawyers around Huber against the idealist faction led by Lucie Odier, a former nurse.

[2] When Nazi Germany started its Western Campaign on 10 May 1940 by invading the neutral states of the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxemburg, Chenevière reacted immediately by expanding the Central Agency.

In order to cope with the information which came in as an unprecedented flood due to the new dimensions of human suffering, Chenevière introduced a modern data processing system which used punched cards.

The Swiss ambassador in Bucharest, René de Weck (1887–1950), who as a romand poet and novelist was an old friend of Chenevière's, sent a private letter to him[54] with an alarming message:«Dear Chenevière, As I am sure you are aware, the Jews of Romania have for some time, particularly since the country's declaration of war against the USSR, been the object of systematic persecution, compared to which the massacres in Armenia which aroused such indignation in Europe at the dawn of our century seem as harmless as children's games.

[..] inhuman acts of violence, despoilments of every kind, deportations, executions and massacres which have taken place.»De Weck strongly suggested that the ICRC send a delegate under the pretext of another mission to Romania where he could then gather relevant information.

De Weck was certain that thanks to the reputation of the ICRC the Romanian government would not ignore the resulting recommendations: «Thousands of lives now under threat could thus be saved.» However, despite the urging, Chenevière only replied more than a month later that «we do not feel able to resolve the question which you put to me».

[55] In the same year, he took over the editorship of the book review page at the Journal de Genève,[56] a liberal daily newspaper, which had contributed to the founding of the ICRC by publishing a report by Dunant about the Battle of Solferino.

In the plenary session on 14 October a clear majority of its members – led by Marguerite Frick-Cramer, Suzanne Ferrière and Lucie Odier – supported as the ultimate intervention a public denouncation of the genocide.

Chenevière warned on several other occasions as well about the consequences of any extension of its protection efforts and insisted that the ICRC should stick to its traditional operations, especially taking care of POWs.

However, he deliberately failed to mention the fact that his friend de Weck had suggested to him in 1941 a promising way to obtain independent information:«People have expressed surprise that the ICRC did not protest publicly while there was still time.

In the absence of hard proof they were taken by the accused country as evidence of a priori bias, and put in jeopardy the other activities which the Red Cross was duty bound under the Conventions to carry out.

The afore-mentioned is the description of a tragic problem and not an act of self-justification.»[4]In May 1947, Chenevière as well as his old friend Jaques-Dalcroze and the painter Alexandre Blanchet received the Prize of Geneva in the city's theatre.

He thus continued to participate both in daily politics and strategic decisions, especially with regard to the humanitarian crises in Algeria,[68] Greece, Indochina, Indonesia, Korea, Palestine / Israel, Syria, and Tunisia.

[48] However, in June of the same year he still delivered the main speech at the Zürich Town Hall during the award ceremony for the Great Prize of the foundation which honoured Gonzague de Reynold,[70] Chenevière's old friend[53] who as an apologist of Switzerland's aristocratic past and sympathiser of authoritarian regimes was very controversial back then and has remained so ever since.

At the end of the same year, the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium awarded him its Grand Prize for French-language literature from outside of France.

[3] Jacques Chenevière was buried in between the graves of his parents and his mother-in-law on the cemetery of Collonge-Bellerive, a municipality on Lake Geneva's left bank, where he had a second residency on the shores.