James Connolly

From 1905 to 1910, he was a full-time organiser in the United States for the Industrial Workers of the World, choosing its syndicalism over the doctrinaire Marxism of Daniel DeLeon's Socialist Labor Party of America, to which he had been initially drawn.

Greaves reports that Connolly reminisced about being on military guard duty in Cork Harbour on the night in December 1882 when Maolra Seoighe was hanged for the Maamtrasna massacre (the killing of a landlord and his family).

[4]: 26 This might suggest that, having been listed in the census of the previous year as a 12-year old baker's apprentice,[3]: 7 Connolly had falsified his age and name to enlist in the 1st Battalion, King’s Liverpool Regiment (recruited heavily from the Irish in Britain).

[15][12]: 17 Milligan, who deferred to the Irish Republican Brotherhood (in 1899 they had her pass her subscription list to Griffith and his new weekly, the United Irishman, the forerunner of Sinn Féin),[16] confined her response to Connolly's ambition to contest Westminster elections.

[4]: 63 In 1900, Connolly had supported the American Marxist Daniel De Leon in condemning the decision by the French socialist Alexander Millerand, at the height of the Dreyfus Affair, to accept a post in Pierre Waldeck-Rousseau’s government of “Republican Defence”.

In a city in which the Protestant-dominated apprenticed trades were organised in British-aligned craft unions, troops had been deployed in 1907 to break strikes Larkin had called among dock labourers, carters and other casual and general workers.

In response to the speeding up of production in the mills and, relatedly, the fining of workers for such new offences as laughing, whispering and bringing in sweets (the creation, in Connolly words, of "an atmosphere of slavery"),[18]: 152 thousands of spinners went out on strike.

[18]: 152 [12]: 112 He then sought to capitalise on the relative success of the tactic by building up, first with Marie Johnson and then Winifred Carney as its secretary, a new – effectively women's – section of the ITGWU, the Irish Textile Workers' Union (ITWU).

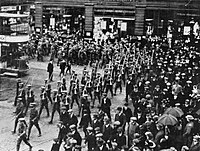

[36] By the end of September, the combination of the "lock out", the sympathetic strikes Larkin called for in response, and their knock-on effects, had placed upwards of 100,000 people (workers and their families, a third of the city's residents) in need of assistance.

[38]: 65 In the hope of replicating a tactic that for Elizabeth Gurley Flynn had turned the tide in the recent, and celebrated, textile strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts,[39] Dora Montefiore had devised a children's "holiday scheme".

Exhausted, and falling into bouts of depression, Larkin took a declining interest in the beleaguered union, and eventually in October accepted an invitation from "Big Bill" Haywood of the IWW to speak in the United States.

[2]: 333 First floated as an idea by George Bernard Shaw,[46] the training of union men as a force to protect picket lines and rallies was taken up in Dublin by "Citizens Committee" chair, Jack White, himself the victim of a police baton charge.

The Irish Citizen Army (ICA) began drilling in November 1913, but then, after it had dwindled like the strike to almost nothing, in March 1914 the militia was reborn, its ranks supplemented by Constance Markievicz's Fianna Éireann nationalist youth.

[48][18]: 198 After the return to work, the command of the ICA divided on the militia's future, and in particular on policy toward the Irish Volunteers, the much larger nationalist response to the arming of Ulster Unionism (and of which Markievicz was also a member).

This left 13,500 to reorganise under the nominal command of Eoin MacNeill of Gaelic League but, in key staff positions, directed by undercover members of the IRB's Military Council: Patrick Pearse, Thomas MacDonagh and Joseph Plunkett.

Accompanied by the martial-patriotic poetry of Maeve Cavanagh, Connolly's editorials continued to urge Irish resistance,[56] and on the express understanding that this could not "be conducted on the lines of dodging the police, or any such high jinks of constitutional agitation".

[57] He cautioned that those who oppose conscription (the prospect that was drawing crowds to the meetings, the marches and parades of the Irish Citizen Army and of the Volunteers) "take their lives in their hands" (and, by implication, that they should organise accordingly).

[49] Labour was not their cause, so that when he himself had proposed a programme for the Irish Volunteers in October 1914, he had confined it to political demands: "repeal of all clauses of the Home Rule Act denying Ireland powers of self-government now enjoyed by South Africa, Australia or Canada".

Ten days later, on Easter Monday, with Connolly commissioned by the IRB Military Council as Commandant of the Dublin Districts, they set out for the General Post Office (GPO) with an initial garrison party from Liberty Hall.

[66]: 304–305 Satisfied that "the glorious stand which has been made by the soldiers of Irish freedom" was "sufficient to gain recognition of Ireland's national claim at an international peace conference", and "desirous of preventing further slaughter of the civilian population", Pearse recorded the "majority" decision.

In a statement to the court martial held in Dublin Castle on 9 May, he proposed offering no defence, save against "charges of wanton cruelty to prisoners”,[70] and he declared:[71]We went out to break the connection between this country and the British Empire, and to establish an Irish Republic.

[68] But at the time, the greater outrage was over the executions of William Pearse, put to death, it was thought, simply because he was the brother of the rebel leader, and Major John MacBride who played no part in planning the Rising but had fought against Britain in the Boer War.

Writing in 1934, Seán Ó Faoláin described Connolly's political ideas as:an amalgamation of everything he had read that could, according to his viewpoint, be applied to Irish ills, a synthesis of Marx, Davitt, Lalor, Robert Owen, Tone, Mitchel and the rest, all welded together in his Socialist-Separatist ideal.

[81] At the same time, there were writers who, convinced that "Connolly's Irish Catholicism had not been irrevocably blemished by atheistic Marxism",[79]: 46 found parallels between his commitment to industrial unionism and the corporatist doctrines Pope Leo XIII enunciated in his encyclical Rerum novarum (1891).

[44] This was viewed by Connolly, not as a contest of rival imperialisms with no democratic principle at stake, but as a war in which, as the primary aggressor, Britain had presented an Ireland willing to strike for its freedom with a legitimate continental ally.

Greaves concedes that there are formulations in Connolly's thinking that "smack of syndicalism"[4]: 245 —that is, of faith in the ability of the working class to secure a socialist future on the strength, not of a revolutionary party, but of their own labour-union democracy.

Fox considers the view that Connolly "allowed himself to be dragged away from his labour convictions" to be "foolish" and "superficial", arguing that under the unique conditions of the Great War he was compelled to "force the independence issue to the point of armed struggle".

From Kerry, he wrote more loosely of the Socialist Republic organising greater "co-operative effort",[98]: 39 [99]: 13 but in either case it was an analysis that suggested that "the most important struggles for the Irish peasantry would occur not in the countryside, but between labour and capital in the cities".

[127]: 129–130 [3]: 171 Connolly sharply criticised the overtly anti-semitic tone of the British Social Democratic Federation's publications during the Boer War, arguing that they had attempted to "divert the wrath of the advanced workers from the capitalists to the Jews".

In 2019, Irish President Michael D. Higgins opened the Áras Uí Chonghaile | James Connolly Visitor Centre on the Falls Road in Belfast, close to where the labour leader had lived in the city.