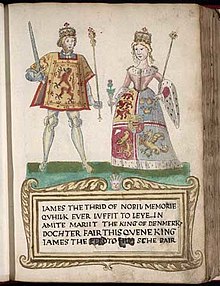

James III of Scotland

He was much criticised by contemporaries and later chroniclers for his promotion of unrealistic schemes to invade or take possession of Brittany, Guelders and Saintonge at the expense of his regular duties as king.

While his reign saw Scotland reach its greatest territorial extent with the acquisition of Orkney and Shetland through his marriage to Margaret of Denmark, James was accused of debasing the coinage, hoarding money, failing to resolve feuds and enforce criminal justice, and pursuing an unpopular policy of alliance with England.

His preference for his own "low-born" favourites at court and in government alienated many of his bishops and nobles, as well as members of his own family, leading to tense relationships with his brothers, his wife, and his heir.

In 1482, James's brother, Alexander, Duke of Albany, attempted to usurp the throne with the aid of an invading English army, which led to the loss of Berwick-upon-Tweed and a coup by a group of nobles which saw the king imprisoned for a time, before being restored to power.

Following the defeat of the Lancastrians by the Yorkists at the Battle of Towton in March 1461, Henry VI of England, Margaret of Anjou, and Edward, Prince of Wales fled north across the border seeking refuge.

[4] The Lancastrians expected Mary to provide them with Scottish troops to help Henry VI recover the throne, but she had no intention of becoming involved in a war on their behalf.

However, Christian I was unable to raise more than 2,000 of the promised 10,000 guilders, and in May 1469, Orkney and Shetland were pledged by him, as king of Norway, to James III as security until the outstanding amount of Margaret's dowry.

James III began his personal rule in 1469, yet his exercise of royal power was affected by the fact that he was one of the few Stewart monarchs who had to contend with the problem of an adult, legitimate brother.

From the positive beginnings after his assumption of active control of government in 1469, James III's relationship with Parliament would lead to opposition, criticism, and outright confrontation over his foreign and domestic policies.

The main business of the parliament James III called in 1471 was the granting of a tax to fund an embassy to the continent to allow him to act as arbitrator between Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, and Louis XI of France.

[17] In February 1472, James's second continental scheme saw him ask Parliament to fund his plan to lead an army of 6,000 men to assert his tenuous claim to the Duchy of Brittany, which derived from his aunt, Isabella.

[19] Duke Arnold died in February 1473, and with him, any serious likelihood of putting his succession plans into effect, but James III was undaunted and sent an ambassador to Charles the Bold to press his claim.

The king's failure to take an active and personal role in the same, and his use of remissions and respites as a source of money, would prove one of the most frequently occurring themes in Parliament for the rest of the reign.

On 20 February 1472, Parliament brought the negotiations[clarification needed], which had begun with the Treaty of Copenhagen, to an end by annexing and uniting the earldom of Orkney and the lordship of Shetland to the Scottish Crown.

[21] This Anglo-Scottish treaty, the first alliance between the two kingdoms in the fifteenth century, preserved the peace between Scotland and England and provided James III with a substantial financial gain.

[23] The confrontation began in September 1475, when John was accused of a number of offences against the Crown, including treasonable dealings with England and the Earl of Douglas, and besieging Rothesay Castle.

The king stood at the height of his power, having removed the Boyds, annexed Orkney and Shetland, humbled the Archbishop of St Andrews, agreed to peace and an alliance with England, and forfeited the Lord of the Isles.

James III's pursuit of unpopular and arbitrary policies saw increasing opposition in Parliament, with the most criticism directed towards the king's failure to go out on Justice Ayres, his making money from granting remissions for serious crimes, and his frequent recourse to taxation.

It has been suggested that the most likely causes of the rift between James and Albany were the latter's opposition to the Anglo-Scottish alliance, his being responsible for serious violations of the truce, and his abuse of his position and challenge to royal authority by the ruthless enforcement of justice in the Marches.

[27] In May 1479, Albany was accused of treason for arming and provisioning Dunbar Castle against the king, assisting known rebels and deliberately causing trouble on the Anglo-Scottish border, in violation of the truce between Scotland and England.

[27] Albany fled by sea to Paris, where in September 1479 he was welcomed by King Louis XI, and received royal favour by his marriage to Anne de La Tour d'Auvergne.

Edward IV continued to pay the annual instalments of the dowry for his daughter's future marriage to James III's heir, and both kingdoms avoided any significant breaches of the truce.

[28] In 1478 James proposed strengthening the alliance with England still further by offering his sister Margaret as a bride for Edward IV's brother-in-law, Anthony Woodville, 2nd Earl Rivers.

However, Edward was prepared to maintain the peace if James would surrender Berwick and hand over his son and heir as a guarantee of his intention to carry through with the marriage of the Duke of Rothesay and Cecily of York.

Whilst imprisoned in Edinburgh Castle, James was politically sidelined from July 1482 to early 1483, and his two half-uncles (including Andrew Stewart) managed to form a brief replacement government with his brother Alexander, Duke of Albany, in place as acting lieutenant-general of the realm.

The death of his patron, Edward IV, on 9 April left Albany in an untenable position and he fled to England, letting an English garrison into his stronghold of Dunbar Castle.

[38] The king made more enemies among his nobles by dismissing the Earl of Argyll from the Chancellorship, for reasons which remain a mystery, and replacing him with William Elphinstone, the Bishop of Aberdeen.

Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie, writing in 1576, states that the king fled to Stirling, but was thrown from his horse and fainted near Milton mill, where he was cared for by the miller and his wife.

There is no evidence available to corroborate any of the sixteenth century allegations of cowardly behaviour, and the subsequent parliamentary account stated only the king "happened to be slain" as a result of his own poor decisions.

His son and successor, James IV, attended the ceremony and in atonement for his involvement in his father's death, from 1496 appointed a chaplain to sing for the salvation of their souls; records of this continued until the Scottish Reformation.