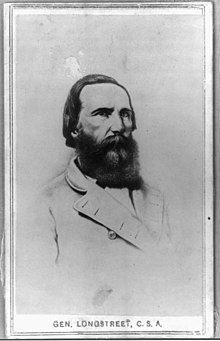

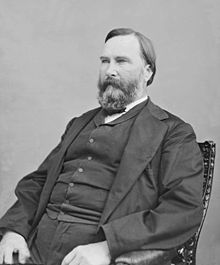

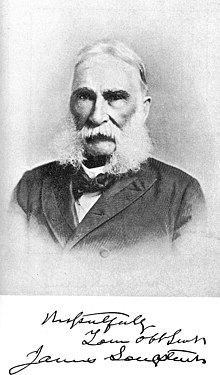

James Longstreet

Longstreet made significant contributions to most major Confederate victories, primarily in the Eastern Theater as one of Robert E. Lee's chief subordinates in the Army of Northern Virginia.

Longstreet's most controversial service was at the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, where he openly disagreed with Lee on the tactics to be employed and reluctantly supervised several unsuccessful attacks on Union forces.

Afterward, Longstreet was, at his own request, sent to the Western Theater to fight under Braxton Bragg, where his troops launched a ferocious assault on the Union lines at Chickamauga that carried the day.

His support for the Republican Party and his cooperation with his pre-war friend President Ulysses S. Grant, as well as critical comments he wrote about Lee's wartime performance, made him anathema to many of his former Confederate colleagues.

But Augustus, as a lawyer, judge, newspaper editor, and Methodist minister, was a fierce states' rights partisan who supported South Carolina during the Nullification crisis (1828–1833), ideas to which Longstreet probably would have been exposed.

Longstreet's engineering instructor in his fourth year was Dennis Hart Mahan, who stressed swift maneuvering, protection of interior lines, and positioning troops in strategic points rather than attempting to destroy the enemy's army outright.

[49][50] Between 5 and 6 in the evening, Longstreet received an order from Brigadier General Joseph E. Johnston instructing him to take part in the pursuit of the Federal troops, who had been defeated and were fleeing the battlefield.

On August 28 and 29, the start of the Second Battle of Bull Run (Second Manassas), Pope pounded Jackson as Longstreet and the remainder of the army marched from the west, through Thoroughfare Gap, to reach the battlefield.

Postwar criticism of Longstreet claimed that he marched his men too slowly, leaving Jackson to bear the brunt of the fighting for two days, but they covered roughly 30 miles (50 km) in a little over 24 hours and Lee did not attempt to get his army concentrated any faster.

The position was naturally strong, made more so by the piling of planks from a wooden fence at the top of the ditch, and Hill's men firmly repulsed two successive charges from the Union divisions of William H. French and Richardson.

The divisions were commanded by Lafayette McLaws, R.H. Anderson, Hood, Pickett, and Robert Ransom Jr.[117][118] After a lengthy interlude with little military activity, beginning on October 26, McClellan marched his army across the Potomac River.

Soldiers attempting to lay pontoon bridges encountered fierce resistance from Confederate troops inside Fredericksburg, led by William Barksdale's brigade of McLaws' division.

Confederate troops were well protected, although they did suffer one notable casualty when Brigadier General Thomas Reade Rootes Cobb, who commanded a brigade in McLaws' division that was positioned at the front of the stone wall, was killed.

All that I could ask was that the policy of the campaign should be one of defensive tactics; that we should work so as to force the enemy to attack us, in such good position as we might find in our own country, so well adapted to that purpose—which might assure us of a grand triumph.

[155] Harrison reported to Longstreet on the evening of June 28 and was instrumental in warning the Confederates that the Army of the Potomac was advancing north to meet them more quickly than they had anticipated, and was already gathered around Frederick, Maryland.

[165][166] Longstreet's soldiers were forced to take a long detour while approaching the enemy position, misled by inadequate reconnaissance that failed to identify a completely concealed route.

[169][170][171] Campaign historian Edwin Coddington presents the approach to the federal positions as "a comedy of errors such as one might expect of inexperienced commanders and raw militia, but not of Lee's 'War Horse' and his veteran troops".

[185][186] Longstreet urged Lee not to use his entire corps in the attack, arguing that the divisions of Law and McLaws were tired from the previous day and that shifting them towards Cemetery Ridge would dangerously expose the Confederate right flank.

Bragg's subordinates had long been dissatisfied with his abrasive personality and poor battlefield record; the arrival of Longstreet (the senior lieutenant general in the Army) and his officers, and the fact that they quickly took their side, added credibility to the earlier claims.

After sending his artillery commander, Porter Alexander, to reconnoiter the Union-occupied town, he devised a plan to shift most of the Army of Tennessee away from the siege, setting up logistical support in Rome, Georgia, to go after Bridgeport to take the railhead, possibly catching Hooker, who was leading a detachment of arriving Union troops from the Eastern Theater, in a disadvantageous position.

[235] He attempted to keep communications open with Lee's army in Virginia, but Federal cavalry Brigadier General William W. Averell's raids destroyed the railroads, isolating him and forcing him to rely only on Eastern Tennessee for supplies.

He developed tactics to deal with difficult terrain, ordering the advance of six brigades by heavy skirmish lines, which allowed his men to deliver a continuous fire into the enemy while proving to be elusive targets themselves.

[245] According to Alexander: "I have always believed that, but for Longstreet's fall, the panic which was fairly underway in Hancock's [II] Corps would have been extended & have resulted in Grant's being forced to retreat back across the Rapidan.

[252][253] For the remainder of the Siege of Petersburg, Longstreet commanded the defenses in front of the capital of Richmond, including all forces north of the James River and Pickett's Division at Bermuda Hundred.

[264] On June 7, 1865, Lee, Longstreet, and other former Confederate officers were indicted by a grand jury in Norfolk, Virginia for the high crime of treason against the United States, a capital offense.

In June 1868, the Radical Republican-controlled United States Congress enacted a law that granted pardons and restored political rights to numerous former Confederate officers, including Longstreet.

[272][273] In April 1873, Longstreet dispatched a police force under Colonel Theodore W. DeKlyne to Colfax, Louisiana, to help the local government and its majority-black supporters defend themselves against an insurrection by white supremacists.

Marshal of Georgia from 1881 to 1884, but the return of a Democratic administration under Grover Cleveland in 1885 ended his political career and he went into semi-retirement on a 65-acre (26 ha) farm near Gainesville, where he raised turkeys and planted orchards and vineyards on terraced ground that his neighbors referred to jokingly as "Gettysburg".

Speaking of Gettysburg on July 2, 1863, he writes: "The battle was being decided at that very hour in the mind of Longstreet, who at his camp, a few miles away, was eating his heart away in sullen resentment that Lee had rejected his long cherished plan of a strategic offensive and a tactical defensive.

At least one historian attributes this to Longstreet's defense of the "rights of the freedmen and women" whereas Forrest was considered the "avenging angel" of American white supremacy and the Lost Cause myth.