James McCune Smith

After it was burned down in July 1863 by a mob in draft riots in Manhattan, in which nearly 100 blacks were killed, Smith moved his family and practice to Brooklyn for their safety.

As an adult, James Smith alluded to other white ancestry through his mother's family, saying he had kin in the South, some of whom were slaveholders and others slaves.

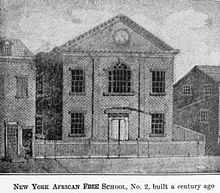

[4] Smith attended the African Free School (AFS) #2 on Mulberry Street in Manhattan, where he was described as an "exceptionally bright student".

[7] He was selected to deliver an oratory to the Marquis de Lafayette, the French war hero who visited the school on September 10, 1824, during his tour of the country.

Upon graduation, he applied to Columbia University and Geneva Medical College in New York State, but was denied admission due to racial discrimination.

According to the historian Thomas M. Morgan, Smith enjoyed the relative racial tolerance in Scotland and England, which judicially abolished slavery in the 1770s.

When he tried to book a trip back to the United States after completing his studies, the ship captain refused passage because of Smith's race.

[12] When Smith did return to Manhattan, he was met with a hero's welcome by his former classmates and teachers who applauded his determination to fight for civil rights on American soil.

[13] After establishing himself upon his return to New York City, in the early 1840s Smith married Malvina Barnett, a free woman of color who had graduated from the Rutgers Female Institute.

[14] The couple had eleven children; five survived to adulthood (the name of one child is unknown):[15] In 1850, the senior Smiths' household included four older women: Lavinia Smith, age 67 (his mother: b. c.1783 – d. bet.1860-1870), born in South Carolina and listed first as head of household; Sarah Williams, 57 (widow of Peter Williams Jr.); Amelia Jones, 47; and Mary Hewlitt, 53, who were likely relatives or friends.

[14] They lived in a mixed neighborhood in the Fifth Ward; in the census, nearly all other neighbors on the page were classified as white; many were immigrants from England, Ireland, and France.

He established what has been called the first black-owned and operated pharmacy in the United States, located at 93 West Broadway (near present-day Foley Square).

[4] In addition to caring for orphans, the home sometimes boarded children temporarily when their parents were unable to support them, as jobs were scarce for free blacks in New York.

In July 1852, he presented the trustees with 5,000 acres of land provided by his friend Gerrit Smith, a wealthy white abolitionist.

He worked effectively with both Black and white abolitionists, for instance maintaining a friendship and correspondence with Gerrit Smith that spanned the years from 1846 to 1865.

His "Destiny of the People of Color", "Freedom and Slavery for Africans", and "A lecture on the Haitian Revolution; with a note on Toussaint L'Ouverture", established him as a new force in the field.

The historian John Stauffer of Harvard University says: "He was one of the leaders within the movement to abolish slavery, and he was one of the most original and innovative writers of his time.

[36] In 1844, Smith published an article entitled "On the Influence of Opium upon the Catamenial Functions" in the New York Journal of Medicine, the earliest known contribution to the medical literature by a Black physician.

[37] In 1843, he gave a lecture series entitled Comparative Anatomy and Physiology of the Races to demonstrate the failings of phrenology, which was a so-called "scientific" practice of the time that was applied in a way to draw racist conclusions and attribute negative characteristics to ethnic Africans.

He showed that Blacks in the North lived longer than slaves, attended church more, and were achieving scholastically at a rate similar to whites.

[29][40] Based on Smith's findings, John Quincy Adams, acting in his capacity in the House of Representatives, called for an investigation of the census results.

Because of his race, Smith's nomination posed a challenge for the fledgling, but rapidly growing academy and its committee on admissions, who wished to avoid "agitation of the question".

In 1854 he was elected as a member by the American Geographical Society (founded in New York in 1851 by top scientists as well as wealthy amateurs interested in exploration).

[43] Among numerous other works supporting abolitionism and dealing with issues related to race, Smith was known for his introduction to Frederick Douglass's second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855).

Smith's commentaries on African-American culture, local and national politics, literature, and styles of dress made him one of the earliest Black public intellectuals to gain popularity in the U.S.[44] In 1859, Smith published an article using scientific findings and analysis to refute the former president Thomas Jefferson's theories of race, as expressed in his well-known Notes on the State of Virginia (1785).

[4] Dr. Vanessa Northington Gamble, a medical physician and historian at George Washington University, in 2010 noted: "As early as 1859, Dr. McCune Smith said that race was not biological but was a social category.

"[22] He commented on the positive ways that ethnic Africans would influence U.S. culture and society, in music, dance, food, and other elements.

His collected essays, speeches, and letters have been published as The Works of James McCune Smith: Black Intellectual and Abolitionist (2006), edited by John Stauffer.

They were relearned by his descendants in the twenty-first century, who identified as white and did not know about him, when a great-great-great-granddaughter took a history class and found his name in her grandmother's family bible.

At the 2018 Discourse and Awards ceremony, NYAM President Judith Salerno presented a replica certificate of fellowship to Professor Joanne Edey-Rhodes, who accepted on behalf of Smith's descendants.