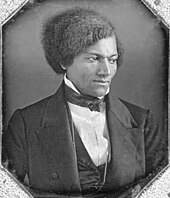

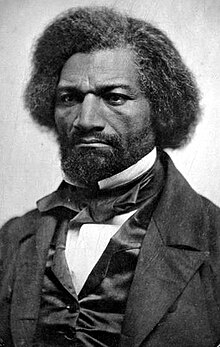

Frederick Douglass

After escaping from slavery in Maryland in 1838, Douglass became a national leader of the abolitionist movement in Massachusetts and New York and gained fame for his oratory[4] and incisive antislavery writings.

Accordingly, he was described by abolitionists in his time as a living counterexample to claims by supporters of slavery that enslaved people lacked the intellectual capacity to function as independent American citizens.

Without his knowledge or consent, Douglass became the first African American nominated for vice president of the United States, as the running mate of Victoria Woodhull on the Equal Rights Party ticket.

[8] When radical abolitionists, under the motto "No Union with Slaveholders", criticized Douglass's willingness to engage in dialogue with slave owners, he replied: "I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong.

He later learned that his mother had also been literate, about which he would later declare: I am quite willing, and even happy, to attribute any love of letters I possess, and for which I have got—despite of prejudices—only too much credit, not to my admitted Anglo-Saxon paternity, but to the native genius of my sable, unprotected, and uncultivated mother—a woman, who belonged to a race whose mental endowments it is, at present, fashionable to hold in disparagement and contempt.

[40][41][42] Douglass reached Havre de Grace, Maryland, in Harford County, in the northeast corner of the state, along the southwest shore of the Susquehanna River, which flowed into the Chesapeake Bay.

[48][52] In What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?, an oration Douglass gave in the Corinthian Hall of Rochester,[53] he sharply criticized the attitude of religious people who kept silent about slavery, and he charged that ministers committed a "blasphemy" when they taught it as sanctioned by religion.

On his return to the United States, Douglass founded the North Star, a weekly publication with the motto "Right is of no sex, Truth is of no color, God is the Father of us all, and we are all Brethren."

In addition to several Bibles and books about various religions in the library, images of angels and Jesus are displayed, as well as interior and exterior photographs of Washington's Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church.

[58] Throughout his life, Douglass had linked that individual experience with social reform, and, according to John Stauffer, he, like other Christian abolitionists, followed practices such as abstaining from tobacco, alcohol and other substances that he believed corrupted body and soul.

Later, he joined the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, an independent black denomination first established in New York City, which counted among its members Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman.

[71][77][78][79] In 1843, Douglass joined other speakers in the American Anti-Slavery Society's "Hundred Conventions" project, a six-month tour at meeting halls throughout the eastern and midwestern United States.

In a letter to William Lloyd Garrison, Douglass wrote "I see much here to remind me of my former condition, and I confess I should be ashamed to lift up my voice against American slavery, but that I know the cause of humanity is one the world over.

[90] During this trip Douglass became legally free, as British supporters led by Anna Richardson and her sister-in-law Ellen of Newcastle upon Tyne raised funds to buy his freedom from his American owner Thomas Auld.

[89][91] Many supporters tried to encourage Douglass to remain in England but, with his wife still in Massachusetts and three million of his black brethren in bondage in the United States, he returned to America in the spring of 1847,[89] soon after the death of Daniel O'Connell.

"[99] After returning to the U.S. in 1847, using £500 (equivalent to $57,716 in 2023) given to him by English supporters,[89] Douglass started publishing his first abolitionist newspaper, the North Star, from the basement of the Memorial AME Zion Church in Rochester, New York.

"[102] The AME Church and North Star joined in the freedmen community's vigorous opposition to the mostly white American Colonization Society and its proposal to send free black people to Africa.

I remember the chain, the gag, the bloody whip, the deathlike gloom overshadowing the broken spirit of the fettered bondman, the appalling liability of his being torn away from wife and children, and sold like a beast in the market.

[108][109] Yet in his conclusion Douglass shows his focus and benevolence, stating that he has "no malice towards him personally," and asserts that, "there is no roof under which you would be more safe than mine, and there is nothing in my house which you might need for comfort, which I would not readily grant.

His opinion as the editor of a prominent newspaper carried weight, and he stated the position of the North Star explicitly: "We hold woman to be justly entitled to all we claim for man."

After Lincoln had finally allowed black soldiers to serve in the Union army, Douglass helped the recruitment efforts, publishing his famous broadside Men of Color to Arms!

Douglass described the spirit of those awaiting the proclamation: "We were waiting and listening as for a bolt from the sky ... we were watching ... by the dim light of the stars for the dawn of a new day ... we were longing for the answer to the agonizing prayers of centuries.

After delivering the speech, Douglass immediately wrote to the National Republican newspaper in Washington (which published his letter five days later, on April 19), criticizing the statue's design and suggesting the park could be improved by more dignified monuments of free black people.

[75] President Grant sent a congressionally sponsored commission, accompanied by Douglass, on a mission to the West Indies to investigate whether the annexation of Santo Domingo would be good for the United States.

In 1872, Douglass became the first African American nominated for Vice President of the United States, as Victoria Woodhull's running mate on the Equal Rights Party ticket.

In 1881, at Storer College in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, Douglass delivered a speech praising John Brown and revealing unknown information about their relationship, including their meeting in an abandoned stone quarry near Chambersburg shortly before the raid.

With new wife Helen, Douglass toured the UK[166] including Wales (possibly by invitation from abolitionist Jessie Donaldson), Ireland, France, Italy, Egypt, and Greece from 1886 to 1887.

[168] Many African Americans, called Exodusters,[citation needed] escaped the Klan and racially discriminatory laws in the South by moving to Kansas, where some formed all-black towns to have a greater level of freedom and autonomy.

[180] A marker, erected by the University of Rochester and other friends, describes him as "escaped slave, abolitionist, suffragist, journalist and statesman, founder of the Civil Rights Movement in America".

[180] Biographer David Blight states that Douglass "played a pivotal role in America's Second Founding out of the apocalypse of the Civil War, and he very much wished to see himself as a founder and a defender of the Second American Republic.