Jamestown Exposition

The Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities had gotten the ball rolling in 1900 by calling for a celebration to honor the establishment of the first permanent English colony in the New World at Jamestown, to be held on the 300th anniversary.

There were no local facilities to handle large crowds, and it was believed that the fort housing the settlement had long ago been swallowed by the James River.

Norfolk is today the center of the most populous portion of Virginia, and every historical, business and sentimental reason can be adduced in favor of the celebration taking place here rather than in Richmond."

The Dispatch was an unrelenting champion of Norfolk as the site for the exposition, noting in subsequent editorials that "Richmond has absolutely no claim to the celebration except her location on the James River."

Opening day was April 26, 1907, exactly 300 years after Christopher Newport and his band of English colonists made their first landing in Virginia at the point where the southern shore of the Chesapeake Bay meets the Atlantic Ocean.

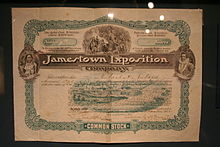

The Exposition Company had initially lobbied the federal government for $1,640,000 and received a loan for an additional million, to be repaid through a lien on 40% of the gate receipts.

When crowds failed to appear in the anticipated numbers—the exposition was attracting an average of 13,000 visitors daily, only 7,400 of whom paid entrance—the company could repay only $140,000 of the million-dollar loan.

The fair began attracting negative attention in the press as early as January before it opened, as a divisive split between planning committee members became public.

The press who arrived for the opening day found the grounds unfinished, the hotels overpriced, and the transportation between the fair and nearby towns insufficient.

Source:[3] The event included the naval review of warship fleets on June 10 by President Theodore Roosevelt, who arrived on the presidential yacht Mayflower.

The US Navy warships remained in Hampton Roads after the exposition closed and became President Theodore Roosevelt's Great White Fleet under Admiral Evans, which toured the globe as evidence of the nation's military might.

The same section was later installed underwater as part of the link to the new Penn Station in New York City, with an inscription that it had been displayed at the Jamestown Exposition.

A controversial feature of the exposition was its "Negro Building," designed by W. Sydney Pittman, which displays showed the progress of African Americans.

Richmond lawyer and businessman Giles Beecher Jackson was a leader in the formation of the Negro Department at the Jamestown Exposition and had worked hard to raise funds for the exhibition.

The organizer, Giles B. Jackson, felt that having the exhibition in a separate Negro Hall allowed for a greater variety and completeness of presentation and that it could better highlight the achievements of African Americans.

A series of dioramas by Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, a black woman artist from Philadelphia, comprised the first artwork done by an African American with federal funds.

Although most commercial ventures lost money, the branch bank in the Negro Hall, affiliated with a local African-American institution, recorded one of the Exposition's only profits, doing $75,731.87 in business in the course of the fair.

[9] In conjunction with the first day of Exposition, the U.S. Post Office issued a series of three commemorative stamps celebrating the 300th anniversary of the founding of Jamestown.

The new Naval Base was aided by the improvements remaining from the Exposition, the strategic location at Sewell's Point on Hampton Roads, and the large amount of vacant land in the area.

The coal piers and storage yards of the Virginian Railway (VGN), built by William N. Page and Henry H. Rogers and completed in 1909, were immediately adjacent to the Exposition site.

The well-engineered VGN was a valuable link directly to the bituminous coal of southern West Virginia, which the Navy strongly preferred for its steam-powered ships.

On June 28, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson set aside $2.8 million for land purchase and the erection of storehouses and piers for what was to become the Navy Base.