Theodore Roosevelt

The New York state party leadership disliked his ambitious agenda and convinced McKinley to choose him as his running mate in the 1900 presidential election; the McKinley–Roosevelt ticket won a landslide victory.

As a leader of the progressive movement, he championed his "Square Deal" domestic policies, which called for fairness for all citizens, breaking bad trusts, regulating railroads, and pure food and drugs.

[25] After the deaths of his wife and mother, Roosevelt focused on his work, specifically by re-energizing a legislative investigation into corruption of the New York City government, which arose from a bill proposing power be centralized in the mayor's office.

[34] Roosevelt attended the 1884 Republican National Convention in Chicago, where he gave a speech convincing delegates to nominate African American John R. Lynch, an Edmunds supporter, to be temporary chair.

He bragged: "We achieved a victory in getting up a combination to beat the Blaine nominee for temporary chairman...this needed...skill, boldness and energy... to get the different factions to come in... to defeat the common foe.

[55][56] Fearing his political career might never recover, Roosevelt turned to writing The Winning of the West, tracking the westward movement of Americans; it was a great success, earning favorable reviews and selling all copies from the first printing.

[64] Roosevelt's close friend and biographer, Joseph Bucklin Bishop, described his assault on the spoils system: The very citadel of spoils politics, the hitherto impregnable fortress that had existed unshaken since it was erected on the foundation laid by Andrew Jackson, was tottering to its fall under the assaults of this audacious and irrepressible young man... Whatever may have been the feelings of the (fellow Republican party) President (Harrison)—and there is little doubt that he had no idea when he appointed Roosevelt that he would prove to be so veritable a bull in a china shop—he refused to remove him and stood by him firmly till the end of his term.

[67] In 1894, Roosevelt met Jacob Riis, the muckraking Evening Sun journalist who was opening the eyes of New Yorkers to the terrible conditions of the city's immigrants with such books as How the Other Half Lives.

The lawbreaker found it out who predicted scornfully that he would "knuckle down to politics the way they all did", and lived to respect him, though he swore at him, as the one of them all who was stronger than pull... that was what made the age golden, that for the first time a moral purpose came into the street.

[69] He made a concerted effort to uniformly enforce New York's Sunday closing law; in this, he ran up against Tom Platt and Tammany Hall—he was notified the Police Commission was being legislated out of existence.

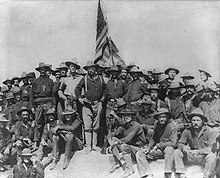

The regiment trained for several weeks in San Antonio, Texas; in his autobiography, Roosevelt wrote that his experience with the New York National Guard enabled him to immediately begin teaching basic soldiering skills.

The rules for the Square Deal were "honesty in public affairs, an equitable sharing of privilege and responsibility, and subordination of party and local concerns to the interests of the state at large".

[120] House Speaker Joseph Gurney Cannon commented on Roosevelt's desire for executive branch control: "That fellow at the other end of the avenue wants everything from the birth of Christ to the death of the devil."

Naval Academy, revising disciplinary rules, altering the design of a disliked coin, and ordering simplified spellings for 300 words, though he rescinded the latter after ridicule from the press and a House protest.

In the 1906 Hepburn Act, Roosevelt sought to give the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) the power to regulate rates, but the Senate, led by conservative Nelson Aldrich, resisted.

[135] He worked closely with Interior Secretary James Rudolph Garfield and Chief of the United States Forest Service Gifford Pinchot to enact a series of conservation programs that met resistance from Western Congress members, such as Charles William Fulton.

However, in August, Roosevelt had exploded in anger at the super-rich for their economic malfeasance, calling them "malefactors of great wealth" in a major speech, "The Puritan Spirit and the Regulation of Corporations".

The Great Rapprochement had begun with British support of the United States during the Spanish–American War, and it continued as Britain withdrew its fleet from the Caribbean in favor of directing most of its attention to the rising German naval threat.

[165] The latitude granted to the Europeans by the arbiters was in part responsible for the "Roosevelt Corollary" to the Monroe Doctrine, which the President issued in 1904: Chronic wrongdoing or an impotence which results in a general loosening of the ties of civilized society, may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention by some civilized nation, and in the Western Hemisphere, the adherence of the United States to the Monroe doctrine may force the United States, however reluctantly, in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international police power.

Their endeavor is to overthrow and discredit all who honestly administer the law, to prevent any additional legislation which would check and restrain them, and to secure if possible a freedom from all restraint which will permit every unscrupulous wrongdoer to do what he wishes unchecked provided he has enough money....The methods by which the Standard Oil people and those engaged in the other combinations of which I have spoken above have achieved great fortunes can only be justified by the advocacy of a system of morality which would also justify every form of criminality on the part of a labor union, and every form of violence, corruption, and fraud, from murder to bribery and ballot box stuffing in politics.

In Oslo, Roosevelt delivered a speech calling for limitations on naval armaments, a strengthening of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, and the creation of a "League of Peace" among the world powers.

Roosevelt's crew consisted of his son Kermit, Colonel Rondon, naturalist George Kruck Cherrie, Brazilian Lieutenant João Lira, team physician José Antonio Cajazeira, and 16 skilled paddlers and porters.

[269] Despite Roosevelt's continued decline and loss of 50 pounds (23 kg), Rondon reduced the pace for map-making, which required regular stops to fix their position by sun-based survey.

Accordingly, he told the 1918 state convention of the Maine Republican Party that he stood for old-age pensions, insurance for sickness and unemployment, construction of public housing for low-income families, the reduction of working hours, aid to farmers, and more regulation of large corporations.

A few years earlier, naturalist John Burroughs had published an article entitled "Real and Sham Natural History" in the Atlantic Monthly, attacking popular writers of the day such as Ernest Thompson Seton, Charles G. D. Roberts, and William J.

[311] As governor of New York, he boxed with sparring partners several times each week, a practice he regularly continued as president until being hit so hard in the face he became blind in his left eye (a fact not made public until many years later).

[312] Roosevelt was an enthusiastic singlestick player and, according to Harper's Weekly, showed up at a White House reception with his arm bandaged after a bout with General Leonard Wood in 1905.

... Like many young men tamed by civilization into law-abiding but adventurous living, he needed an outlet for the pent-up primordial man in him and found it in fighting and killing, vicariously or directly, in hunting or in war.

[217] In the analysis by Henry Kissinger, Roosevelt was the first president to develop the guideline that it was the duty of the United States to make its enormous power and potential influence felt globally.

As for world government: I regard the Wilson–Bryan attitude of trusting to fantastic peace treaties, too impossible promises, to all kinds of scraps of paper without any backing in efficient force, as abhorrent.