Jan Swammerdam

His father Jan (or Johannes) Jacobsz (-1678) was an apothecary and an amateur collector of minerals, coins, fossils, and insects from around the world.

[1] The couple lived across the Montelbaanstoren, near the harbour, the headquarter and the warehouses of the Dutch West India Company where an uncle worked.

Swammerdam accused Reinier de Graaf of taking credit of discoveries he and Van Horne had made earlier regarding the importance of the ovary and its eggs.

Swammerdam declared war on "vulgar errors" and the symbolic interpretation of insects was, in his mind, incompatible with the power of God, the almighty architect.

[10] Swammerdam, therefore, dispelled the seventeenth-century notion of metamorphosis —the idea that different life stages of an insect (e.g. caterpillar and butterfly) represent different individuals[11] or a sudden change from one type of animal to another.

His 1675 treatise on the mayfly, entitled Ephemeri vita, included devout poetry and documented his religious experiences.

In a letter to Henry Oldenburg, he explained "I was never at any time busier than in these days, and the chief of all architects has blessed my endeavors".

It remained unpublished when he died in 1680 and was published as Bybel der natuure posthumously in 1737 by the Leiden University professor Herman Boerhaave.

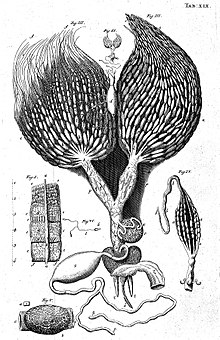

Inspired by Marcello Malpighi, in De Bombyce Swammerdam described the anatomy of silkworms, mayflies, ants, stag beetles, cheese mites, bees and many other insects.

In 1609 Charles Butler had recorded the sex of drones as male, but he wrongly believed that they mated with worker bees.

Swammerdam played a key role in the debunking of the balloonist theory, the idea that 'moving spirits' are responsible for muscle contractions.

The idea, supported by the Greek physician Galen, held that nerves were hollow and the movement of spirits through them propelled muscle motion.

To test this idea, Swammerdam placed severed frog thigh muscle in an airtight syringe with a small amount of water in the tip.

[22] A letter from Steno to Malpighi from 1675 suggests that Swammerdam's findings on muscle contraction had caused his crisis of consciousness.

Steno sent Malpighi the drawings Swammerdam had done of the experiments, saying "when he had written a treatise on this matter he destroyed it and he has only preserved these figures.

[13] Though Swammerdam's work on insects and anatomy was significant, many current histories remember him as much for his methods and skill with microscopes as for his discoveries.

He developed new techniques for examining, preserving, and dissecting specimens, including wax injection to make viewing blood vessels easier.

[6] He had corresponded with contemporaries across Europe and his friends Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and Nicolas Malebranche used his microscopic research to substantiate their own natural and moral philosophy.

[13] But Swammerdam has also been credited with heralding the natural theology of the 18th century, were God's grand design was detected in the mechanics of the Solar System, the seasons, snowflakes and the anatomy of the human eye.

[24] The portrait shown in the header is derived from the painting The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Tulp by Rembrandt and represents the leading Amsterdam physician Hartman Hartmanzoon (1591–1659).