Japamala

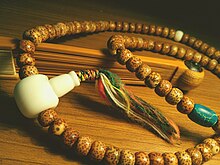

A japamala, jaap maala, or simply mala (Sanskrit: माला; mālā, meaning 'garland'[1]) is a loop of prayer beads commonly used in Indian religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism.

[2][3] The main body of a mala usually consists of 108 beads of roughly the same size and material as each other, although smaller versions, often factors of 108 such as 54 or 27, exist.

[2] Mala beads have traditionally been made of a variety of materials such as wood, stone, gems, seeds, bone and precious metals—with various religions often favouring certain materials—and strung with natural fibres such as cotton, silk, or animal hair.

Malas are similar to other forms of prayer beads used in various world religions, such as the misbaha in Islam and the rosary in Christianity.

[4] No references to malas occur in Chinese literature before the introduction of Buddhism during the Han dynasty, suggesting that the practice may have originated in India, and then spread to China.

[4] Malas may appear in early Hindu art as part of the garb of deities or worshippers, but are difficult to distinguish from decorative necklaces or garlands.

[4] The first literary reference to the use of a mala for the recitation of mantras comes from the Mu Huanzi Jing (木槵子經 or 佛說木槵子經, "Aristaka/Soap-Berry Seed Scripture/Classic", Taishō Tripiṭaka volume 17, number 786), a Mahayana Buddhist text purported to have been translated into Chinese during the Eastern Jin era, sometime in the 4th - 5th century CE.

According to this text, a king asks the Buddha for "an essential method that will allow me during the day or night to engage easily in a practice for freeing us from all sufferings in the world in the future.

The text also states the mala should be worn at all times, and that if a million recitations were completed, the king would end the one hundred and eight passions.

[4][2] Another Mahayana Buddhist source which teaches the use of a mala is found in the Chinese canon in The Sutra on the Yoga Rosaries of the Diamond Peak (金剛頂瑜伽念珠経, Ch.

It also states that wearing a tulasi mala will multiply the benefit of doing good karmic deeds, as well as providing magical protection from harm.

While there are relatively few pre-Song dynasty depictions or references to the mala, this may be due to its use in private religious practice rather than public ceremony.

[4] By the Ming dynasty-era, malas increasingly began to be valued for their aesthetic qualities as much or more than their spiritual use and were often worn by royals and high officials.

[4] Depictions of Qing dynasty court officials often include malas, intended to show their status and wealth rather than as an indication of spirituality.

[2] Strings may be made from practically any fibre, traditionally silk or wool or cotton though synthetic monofilaments or cords such as nylon can now be found and are favoured for their low cost and good wear resistance.

[citation needed] Beads made from the fruitstones of the rudraksha tree (Elaeocarpus ganitrus) are considered sacred by Saivas, devotees of Siva, and its use is taught in the Rudrakshajabala Upanishad.

It is believed that the Rudraksha Japa Mala epitomizes ancient wisdom and mystical energies, offering seekers a conduit to inner peace and spiritual harmony.

The bead itself is very hard and dense, ivory-coloured (which gradually turns a deep golden brown with long use), and has small holes (moons) and tiny black dots (stars) covering its surface.

For example:[14][12][16] One type of wooden mala bead has a shallow trench engraved around their equator into which tiny pieces of red coral and turquoise are affixed.

[citation needed] In Nepal, mala beads are made from the natural seeds of Ziziphus budhensis, a plant in the family Rhamnaceae endemic to the Temal region of Kavrepalanchok in Bagmati Province.

[17] The Government of Nepal's Ministry of Forestry has established a committee and begun to distribute seedlings of these plant so as to uplift the economic status of the people living in this area.

[2] During devotional services, the beads may be rubbed together with both hands to create a soft grinding noise, which is considered to have a purifying and reverential effect.

[2] Meanwhile, in Jōdo Shinshū (True Pure Land), prayer beads are typically shorter and held draped over both hands and are not ground together, as this is forbidden.

They may or may not have religious symbolism (for example, three beads representing the Buddhist Triple Gem of Buddha, Dharma and Sangha) but are not used for counting recitations in any way.

[citation needed] The main use of a mala is to repeat mantras or other important religious phrases and prayers (like the Pure Land Buddhist nianfo).

[4][3] Buddhist sources such as the Sutra of Mañjuśrï’s Fundamental Ritual state that wearing a mala can purify bad karma and ward off evil spirits.

[2] In some traditions, malas are consecrated before use in a manner similar to images of deities, through the use of mantras, dharani, or the application of some substance or pigment like saffron water.

[24] Some Tibetan Buddhist teachers teach that it is a root samaya (tantric commitment) that a consecrated and blessed mala should always be kept on one's person.

[23] For Tibetan Buddhists, the mala is a symbol of their yidam meditation deity and a reminder of their main mantra and tantric commitments (samayas).

[22] Similar practices have been noted since the Ming dynasty, when malas began to be used as fashionable accessories by members of the Chinese court.