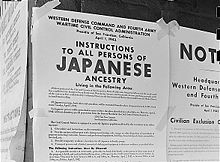

Internment of Japanese Americans

Following the executive order, the entire West Coast was designated a military exclusion area, and all Japanese Americans living there were taken to assembly centers before being sent to concentration camps in California, Arizona, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and Arkansas.

"[16] A subsequent report by Kenneth Ringle (ONI), delivered to the President in January 1942, also found little evidence to support claims of Japanese American disloyalty and argued against mass incarceration.

[18] The surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, led military and political leaders to suspect that Imperial Japan was preparing a full-scale invasion of the United States West Coast.

[33] By February, Earl Warren, the Attorney General of California (and a future Chief Justice of the United States), had begun his efforts to persuade the federal government to remove all people of Japanese ethnicity from the West Coast.

Austin E. Anson, managing secretary of the Salinas Vegetable Grower-Shipper Association, told The Saturday Evening Post in 1942: We're charged with wanting to get rid of the Japs for selfish reasons.

[33] Columnist Henry McLemore, who wrote for the Hearst newspapers, reflected the growing public sentiment that was fueled by this report: I am for the immediate removal of every Japanese on the West Coast to a point deep in the interior.

Hoiles, publisher of the Orange County Register, argued during the war that the incarceration was unethical and unconstitutional: It would seem that convicting people of disloyalty to our country without having specific evidence against them is too foreign to our way of life and too close akin to the kind of government we are fighting.... We must realize, as Henry Emerson Fosdick so wisely said, 'Liberty is always dangerous, but it is the safest thing we have.

Greenberg argues that at the time, the incarceration was not discussed because the government's rhetoric hid the motivations for it behind a guise of military necessity, and a fear of seeming "un-American" led to the silencing of most civil rights groups until years into the policy.

[94] This earlier, racist and inflammatory version, as well as the FBI and Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) reports, led to the coram nobis retrials which overturned the convictions of Fred Korematsu, Gordon Hirabayashi and Minoru Yasui on all charges related to their refusal to submit to exclusion and incarceration.

A Los Angeles Times editorial dated February 19, 1942, stated that: Since Dec. 7 there has existed an obvious menace to the safety of this region in the presence of potential saboteurs and fifth columnists close to oil refineries and storage tanks, airplane factories, Army posts, Navy facilities, ports and communications systems.

Under normal sensible procedure not one day would have elapsed after Pearl Harbor before the government had proceeded to round up and send to interior points all Japanese aliens and their immediate descendants for classification and possible incarceration.

[98]A Washington Post editorial dated February 22, 1942, stated that: There is but one way in which to regard the Presidential order empowering the Army to establish "military areas" from which citizens or aliens may be excluded.

The population of these camps included approximately 3,800 of the 5,500 Buddhist and Christian ministers, school instructors, newspaper workers, fishermen, and community leaders who had been accused of fifth column activity and arrested by the FBI after Pearl Harbor.

The stables and livestock areas were cleaned out and hastily converted to living quarters for families of up to six,[117] while wood and tarpaper barracks were constructed for additional housing, as well as communal latrines, laundry facilities, and mess halls.

[133][page needed] The Heart Mountain War Relocation Center in northwestern Wyoming was a barbed-wire-surrounded enclave with unpartitioned toilets, cots for beds, and a budget of 45 cents daily per capita for food rations.

[137][page needed] Before the war, 87 physicians and surgeons, 137 nurses, 105 dentists, 132 pharmacists, 35 optometrists, and 92 lab technicians provided healthcare to the Japanese American population, with most practicing in urban centers like Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle.

As the eviction from the West Coast was carried out, the Wartime Civilian Control Administration worked with the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) and many of these professionals to establish infirmaries within the temporary assembly centers.

Overcrowded and unsanitary conditions forced assembly center infirmaries to prioritize inoculations over general care, obstetrics, and surgeries; at Manzanar, for example, hospital staff performed over 40,000 immunizations against typhoid and smallpox.

[4] Despite a shortage of healthcare workers, limited access to equipment, and tension between white administrators and Japanese American staff, these hospitals provided much-needed medical care in camp.

[146] In January 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued what came to be known as the "Green Light Letter" to MLB Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, which urged him to continue playing Major League Baseball games despite the ongoing war.

[151] Outside camp, the students took on the role of "ambassadors of good will", and the NJASRC and WRA promoted this image to soften anti-Japanese prejudice and prepare the public for the resettlement of Japanese Americans in their communities.

[198] Lieutenant General Delos C. Emmons, the commander of the Hawaii Department, promised that the local Japanese American community would be treated fairly as long as it remained loyal to the United States.

On September 2, 1943, the Swedish ship MS Gripsholm departed the U.S. with just over 1,300 Japanese nationals (including nearly a hundred from Canada and Mexico) en route for the exchange location, Marmagao, the main port of the Portuguese colony of Goa on the west coast of India.

Civil rights attorney Wayne Collins filed injunctions on behalf of the remaining internees,[189][213] helping them obtain "parole" relocation to the labor-starved Seabrook Farms in New Jersey.

[217] Although War Relocation Authority (WRA) Director Dillon Myer and others had pushed for an earlier end to the incarceration, the Japanese Americans were not allowed to return to the West Coast until January 2, 1945, after the November 1944 election, so as not to impede Roosevelt's reelection campaign.

It asked for three measures: $25,000 to be awarded to each person who was detained, an apology from Congress acknowledging publicly that the U.S. government had been wrong, and the release of funds to set up an educational foundation for the children of Japanese American families.

[245] On September 27, 1992, the Civil Liberties Act Amendments of 1992, appropriating an additional $400 million to ensure all remaining detainees received their $20,000 redress payments, was signed into law by President George H. W. Bush.

[246] Under the 2001 budget of the United States, Congress authorized the preservation of ten detention sites as historical landmarks: "places like Manzanar, Tule Lake, Heart Mountain, Topaz, Amache, Jerome, and Rohwer will forever stand as reminders that this nation failed in its most sacred duty to protect its citizens against prejudice, greed, and political expediency".

[251] UCLA Asian American studies professor Lane Hirabayashi pointed out that the history of the term internment, to mean the arrest and holding of non-citizens, could only be correctly applied to Issei, Japanese people who were not legal citizens.

[344] Regarding the Korematsu case, Chief Justice Roberts wrote: "The forcible relocation of U.S. citizens to concentration camps, solely and explicitly on the basis of race, is objectively unlawful and outside the scope of Presidential authority.