Japanese architecture

[8] Partly due, also, to the variety of climates in Japan, and the millennium encompassed between the first cultural import and the last, the result is extremely heterogeneous, but several practically universal features can nonetheless be found.

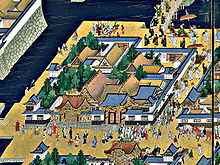

[8] The slightly curved eaves extend far beyond the walls, covering verandas, and their weight must therefore be supported by complex bracket systems called tokyō, in the case of temples and shrines.

During the three phases of the Jōmon period the population was primarily hunter-gatherer with some primitive agriculture skills and their behaviour was predominantly determined by changes in climatic conditions and other natural stimulants.

This last structure is of great importance as an art-historical cache, because in it are stored the utensils that were used in the temple's dedication ceremony in 752, as well as government documents and many secular objects owned by the imperial family.

Although the layout of the city was similar to Nara's and inspired by Chinese precedents, the palaces, temples and dwellings began to show examples of local Japanese taste.

In response to native requirements such as earthquake resistance and shelter against heavy rainfall and the summer heat and sun, the master carpenters of this time responded with a unique type of architecture,[25] creating the Daibutsuyō and Zenshūyō styles.

A good example of this ostentatious architecture is the Kinkaku-ji in Kyōto, which is decorated with lacquer and gold leaf, in contrast to its otherwise simple structure and plain bark roofs.

[6] In the very late part of the period sankin-kōtai, the law requiring the daimyōs to maintain dwellings in the capital was repealed which resulted in a decrease in population in Edo and a commensurate reduction in income for the shogunate.

His influence helped the career of architect Thomas Waters [ja] who designed the Osaka Mint in 1868, a long, low building in brick and stone with a central pedimented portico.

However traditional architecture was still employed for new buildings, such as the Kyūden of Tokyo Imperial Palace, albeit with token western elements such as a spouting water fountain in the gardens.

Constructed with a similar method to traditional (kura (倉)) storehouses, the wooden building plastered inside and out incorporates an octagonal Chinese tower and has stone-like quoins to the corners.

Although his early works like Tōkyō Women's Christian College show Wright's influence,[53] he soon began to experiment with the use of in-situ reinforced concrete, detailing it in way that recalled traditional Japanese construction methods.

Togo Murano, a contemporary of Raymond, was influenced by Rationalism and designed the Morigo Shoten office building, Tōkyō (1931) and Ube Public Hall, Yamaguchi Prefecture (1937).

Buildings in this style were characterised by having a Japanese-style roof such as the Tōkyō Imperial Museum (1937) by Hitoshi Watanabe and Nagoya City Hall and the Aichi Prefectural Government Office.

Taniguchi Yoshirō (谷口 吉郎, 1904–79), an architect, and Moto Tsuchikawa established Meiji Mura in 1965, close to Nagoya, where a large number of rescued buildings are re-assembled.

Examples include the large-scale concept of what is today Ketagalan Boulevard in central Zhongzheng District of Taipei that showcases the Office of the Governor-General, Taiwan Governor Museum, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei Guest House, Judicial Yuan, the Nippon Kangyo Bank and Mitsui Bussan Company buildings, as well as many examples of smaller houses found on Qidong Street.

Many official buildings erected during the colonial period still stand today, including those of the Eight Grand Ministries of Manchukuo, the Imperial Palace, the headquarters of the Kwantung Army and Datong Avenue.

After the war and under the influence of the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, General Douglas MacArthur, Japanese political and religious life was reformed to produce a demilitarised and democratic country.

Venues were constructed and the Yoyogi National Gymnasium, built between 1961 and 1964 by Kenzo Tange, became a landmark structure famous for its suspension roof design, recalling traditional elements of Shinto shrines.

For example, Kazuo Shinohara specialised in small residential projects in which he explored traditional architecture with simple elements in terms of space, abstraction and symbolism.

In the Gunma Prefectural Museum (1971–74) he experimented with cubic elements (some of them twelve metres to a side) overlaid by a secondary grid expressed by the external wall panels and fenestration.

[74] In his 1995 competition win for Sendai Mediatheque, Toyō Itō continued his earlier thoughts about fluid dynamics within the modern city with "seaweed-like" columns supporting a seven-story building wrapped in glass.

[76] Although Tadao Ando became well known for his use of concrete, he began the decade designing the Japanese pavilion at the Seville Exposition 1992, with a building that was hailed as "the largest wooden structure in the world".

[81] For the Nomadic Museum, Ban used walls made of shipping containers, stacked four high and joined at the corners with twist connectors that produced a checkerboard effect of solid and void.

[87] Japanese interior design has a unique aesthetic derived from Shinto, Taoism, Zen Buddhism, world view of wabi-sabi, specific religious figures and the West.

Traditional Japanese interiors, as well as modern, incorporate mainly natural materials including fine woods, bamboo, silk, rice straw mats, and paper shōji screens.

Sei Shōnagon was a trend-setting court lady of the tenth century who wrote in 'The Pillow Book' of her dislike for "a new cloth screen with a colourful and cluttered painting of many cherry blossoms",[91] preferring instead to notice "that one's elegant Chinese mirror has become a little cloudy".

[93] Many public spaces had begun to incorporate chairs and desks by the late nineteenth century, department stores adopted western-style displays; a new "urban visual and consumer culture" was emerging.

One of the examples is the Hōmei-Den of the Meiji era Tokyo Imperial Palace, which fused Japanese styles such as the coffered ceiling with western parquet floor and chandeliers.

[95] During the twentieth century though, a number of now renowned architects visited Japan including Frank Lloyd Wright, Ralph Adams Cram, Richard Neutra and Antonin Raymond.