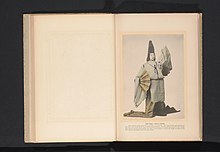

Miko

Traditional miko tools include the Azusa Yumi (梓弓, "catalpa bow"),[7] the tamagushi (玉串) (offertory sakaki-tree branches),[8] and the gehōbako (外法箱, a "supernatural box that contains dolls, animal and human skulls ... [and] Shinto prayer beads").

Miko once performed spirit possession and takusen (whereby the possessed person serves as a "medium" (yorimashi) to communicate the divine will or message of that kami or spirit; also included in the category of takusen is "dream revelation" (mukoku), in which a kami appears in a dream to communicate its will)[11] as vocational functions in their service to shrines.

In addition to a medium or a miko (or a geki, a male shaman), the site of a takusen may occasionally also be attended by a sayaniwa[12] who interprets the words of the possessed person to make them comprehensible to other people present.

[citation needed] As Fairchild explains: Women played an important role in a region stretching from Manchuria, China, Korea and Japan to the [Ryukyu Islands].

In Japan these women were priestesses, soothsayers, magicians, prophets and shamans in the folk religion, and they were the chief performers in organized Shinto.

[17] Miko traditions date back to the prehistoric Jōmon period[1] of Japan, when female shamans[citation needed] would go into "trances and convey the words of the gods"[citation needed] (the kami), an act comparable with "the pythia or sibyl in Ancient Greece.

[22]During the Edo period (1603–1868), writes Groemer, "the organizational structures and arts practiced by female shamans in eastern Japan underwent significant transformations".

To become a shaman, the girl (still at a young age, mostly after the start of the menstruation cycle) had to undergo very intensive training specific to the kuchiyose miko.

This would be done by rituals including washings with cold water, regular purifying, abstinence and the observation of the common taboos like death, illness and blood.

This was achieved by chanting and dancing, thus therefore the girl was taught melodies and intonations that were used in songs, prayers and magical formulas, supported by drum and rattlers.

[citation needed] The resemblance of a wedding ceremony as the initiation rite suggests that the trainee, still a virgin, had become the bride of the kami she served (called a Tamayori Hime (玉依姫)).

After this visit, the woman announced to the public her new position of being possessed by a kami by placing a white-feathered arrow on the roof of her house.

Kuly describes the contemporary miko as: "A far distant relative of her premodern shamanic sister, she is most probably a university student collecting a modest wage in this part-time position.

"[28] The ethnologist Kunio Yanagita (1875–1962), who first studied Japanese female shamans, differentiated them into jinja miko (神社巫女, "shrine shamans") who dance with bells and participate in yudate (湯立て, "boiling water") rituals, kuchiyose miko (ロ寄せ巫女, "spirit medium shamans") who speak on behalf of the deceased, and kami uba (神姥, "god women") who engage in cult worship and invocations (for instance, the Tenrikyo founder Nakayama Miki).

[32] Many scholars identify shamanic miko characteristics in Shinshūkyō ("New Religions") such as Sukyo Mahikari, Ōmoto, and Shinmeiaishinkai.