Japanese craft

[citation needed] Family affiliations or bloodlines are of special importance to the aristocracy and the transmission of religious beliefs in various Buddhist schools.

In Buddhism, the use of the term "bloodlines" likely relates to a liquid metaphor used in the sutras: the decantation of teachings from one "dharma vessel" to another, describing the full and correct transference of doctrine from master to disciple.

[citation needed] Similarly, in the art world, the process of passing down knowledge and experience formed the basis of familial lineages.

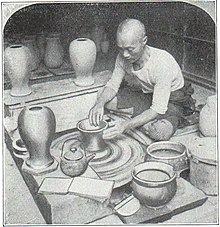

For ceramic, metal, lacquer, and bamboo craftsmen, this acquisition of knowledge usually involved a lengthy apprenticeship with the master of the workshop, often the father of the young disciple, from one generation to the next.

[citation needed] With the end of the Edo period and the advent of the modern Meiji era, industrial production was introduced; western objects and styles were copied and started replacing the old.

Although handmade Japanese craft was once the dominant source of objects used in daily life, modern era industrial production as well as importation from abroad sidelined it in the economy.

Japanese scholar Okakura Kakuzō wrote against the fashionable primacy of western art and founded the periodical Kokka (國華, lit.

Although these objects were designated as National Treasures – placing them under the protection of the imperial government – it took some time for their cultural value to be fully recognized.

The government introduced a new program known as Living National Treasure to recognise and protect craftspeople (individually and as groups) on the fine and folk art level.

Although the government has taken these steps, private sector artisans continue to face challenges trying to stay true to tradition whilst at the same time interpreting old forms and creating new ideas in order to survive and remain relevant to customers.

They also face the dilemma of an ageing society wherein knowledge is not passed down to enough pupils of the younger generation, which means dentō teacher-pupil relationships within families break down if a successor is not found.

Ceramist Tokuda Yasokichi IV was the first female to succeed her father as a master, since he did not have any sons and was unwilling to adopt a male heir.

[2] In 2015, the Museum of Arts and Design in New York exhibited a number of modern kōgei artists in an effort to introduce Japanese craft to an international audience.

Earthenware was created as early as the Jōmon period (10,000–300 BCE), giving Japan one of the oldest ceramic traditions in the world.

[5] Japan is further distinguished by the unusual esteem that ceramics holds within its artistic tradition, owing to the enduring popularity of the tea ceremony.

Village crafts that evolved from ancient folk traditions also continued in the form of weaving and indigo dyeing—by the Ainu people of Hokkaidō (whose distinctive designs have prehistoric prototypes) and by other remote farming families in northern Japan.

Japanese lacquerware is most often employed on wooden objects, which receive multiple layers of refined lac juices, each of which must dry before the next is applied.

These layers make a tough skin impervious to water damage and resistant to breakage, providing lightweight, easy-to-clean utensils of every sort.

The decoration on such lacquers, whether carved through different-colored layers or in surface designs, applied with gold or inlaid with precious substances, has been a prized art form since the Nara period (710–94 CE).

Types of woodwork include:[12][better source needed] Japanese bamboowork implements are produced for tea ceremonies, ikebana flower arrangement and interior goods.

Amongst the more well-known varieties of miscellaneous woodwork are:[12][better source needed] Early Japanese iron-working techniques date back to the 3rd to 2nd century BCE.

Arguably the most important Japanese metalworking technique is forge welding (鍛接), the joining of two pieces of metal—typically iron and carbon steel—by heating them to a high temperature and hammering them together, or forcing them together by other means.

Only relatively late in the Edo period did it experience increased popularity, and with the beginning of modernisation during the Meiji era large-scale industrial production of glassware commenced.