Japanese export porcelain

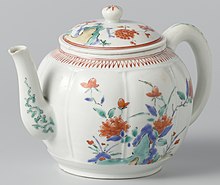

Often the shapes were dictated by the export markets, but the decoration was predominantly East Asian in style, although quite often developed from Dutch imitations of Chinese pieces.

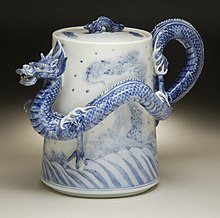

[7] The Dutch also shipped to Japan the large quantities of cobalt required for the underglaze blue colour.

[8] This trade seems to have been preceded by exports of Arita celadon wares to south-east Asia, where most surviving examples appear.

After a few years there seem to have been about twelve kilns around Arita making export wares, and only one or two producing for the domestic market.

But by the 1720s the Chinese wares became more attractive to Europe, in terms of both price and quality, and Japanese exports declined, almost ceasing by the 1740s, by which time European porcelain production was rapidly increasing.

[12] Trade had already reduced from the 1680s on, as the Dutch became occupied with wars in Europe, and the Chinese kilns once again reached full productivity.

[13] Generally the shapes followed European needs, following models provided by the Dutch; large flattish dishes also suited Middle Eastern and Southeast Asian dining requirements.

A large group is decorated in underglaze blue, to which overglaze red and gold, with black for outlines, and sometimes other colours, is added.

But it was shown in Paris, and the local feudal lord had political connections in the West, and it became the most successful export ware, having mostly converted to a porcelain body.

[27] Late 19th-century wares were very heavily decorated, of variable quality, and much criticised on aesthetic grounds at the time and subsequently.

[38] Other pieces carry initials or inscriptions, especially the "VOC" (for Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie) monogram of the Dutch East India Company.

[39] Some pieces can be documented back to the period in old European collections, such as a Kakiemon elephant recorded at Burghley House in England in 1688, and still there.

[40] Although this becomes ever less useful, early period pieces that have a provenance going back a century or more, especially from places in India, southeast Asia or the Middle East, are likely to have been exported to that area after production.

Some shapes were especially made for non-European export markets; the Islamic world wanted large platters for rice-based dishes served communally, and the kendi (or "gargolet") is a distinctive southeast Asian type of drinking or pouring vessel with two openings, one at the top of the neck, and the other lower on the body, with a rounded protuberance.