Japanese immigration in Brazil

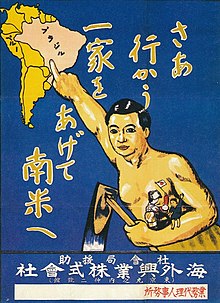

[20] In April 1905, Minister Fukashi Sugimura arrived in Brazil and visited several locations, being well received by both the local authorities and the people; part of this treatment is due to the Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War against the great Russian Empire.

528 signed by President Deodoro da Fonseca and Minister of Agriculture Francisco Glicério determined that the entry of immigrants from Africa and Asia would be allowed only with the authorization of the National Congress.

[24] Francisco José de Oliveira Viana, author of the classic book "Populações Meridionais do Brasil", published in 1918, and Nina Rodrigues, creator of Legal Medicine in Brazil, were the great ideologues of the "whitewashing" of the country.

The first 781 immigrants, introduced under the contract of November 6, 1907, entered the Hospedaria in June of the following year; but, mostly single individuals and little accustomed to farming, they shied away from certain agricultural services, which they gradually abandoned.

[35]Only on June 28, 1910, another ship, the Ryojun Maru, arrived in Santos, bringing another 906 Japanese immigrants, constituting 247 families, divided between 518 men and 391 women, who were sent to work on 17 coffee farms in the State of São Paulo.

The great defender of these ideas was the doctor Miguel Couto (elected by the then Federal District) supported by other medical deputies such as the sanitarian Artur Neiva, from Bahia and Antônio Xavier de Oliveira, from Ceará.

In the following decades after World War II, several decrees were issued determining conditions for the return of what was confiscated, but currently the assets and shares remain in the custody of Banco do Brasil, and the institution and the National Treasury Secretariat admit the existence of this wealth, but do not officially comment on the fact.

In 1939, a survey by the Estrada de Ferro Noroeste do Brasil in São Paulo showed that 87.7% of Japanese-Brazilians subscribed to Japanese-language newspapers, a very high rate considering that a large part of the Brazilian population was illiterate and lived in rural areas.

The Minister of Justice Francisco Campos, in 1941, defended the prohibition of the arrival of 400 Japanese immigrants in São Paulo by writing: Their despicable standard of living represents brutal competition with the country's workers; their selfishness, their bad faith, their refractory character, make them a huge ethnic and cultural cyst located in the richest of Brazil's regions.

[37] Japanese-Brazilians could not travel through the national territory without a pass issued by a police authority; more than 200 schools in the Japanese community were closed; radio sets were seized so that shortwave transmissions from Japan could not be heard.

The Santos newspaper A Tribuna reported on the situation of those trying to dispose of their belongings: "In Marapé, Ponta da Praia and Santa Maria, there was a real rush to sell pigs, chickens, mules, etc.

[54] In 1945, David Nasser and Jean Marzon, the country's most famous journalist-photographer duo, published in O Cruzeiro, the magazine with the largest circulation at the time, an illustrated article in which they intended to teach Brazilians how to distinguish a Japanese from a Chinese.

According to the writer Roney Cytrynowicz, "the oppression against Japanese immigrants, unlike what happened to Italians and Germans in São Paulo, makes it clear that the Estado Novo conducted a large-scale racist campaign against them – under the pretext of accusations of sabotage".

3165 proposed by Miguel Couto Filho (son of the 1934 constituent deputy) was put to a vote, which simply stated: "The entry into the country of Japanese immigrants of any age and from any source is prohibited".

The deputy Miguel Couto Filho often spoke on the rostrum of the constituent assembly defending his constitutional amendment project by quoting a book he had written, the title of which was: "Para o futuro da pátria – Evitemos a niponização do Brasil" (English: For the future of the homeland – Let's avoid the "Japanization" of Brazil).

One of the first political events occurred after a measure imposed by the government of the State of São Paulo, which had the objective of increasing popularity among voters, to make a tabulation of the prices of dyeing services; one of the results of this would be the reduction of the value of washing a suit from 25 to 16 cruzeiros.

As the vast majority of families who moved to São Paulo and Paraná had few resources and were headed by Issei and Nisei, it was mandatory that the business did not require a large initial investment or advanced knowledge of Portuguese.

[61] After World War II, there was a large rural exodus that took most of the Japanese-Brazilian community from the countryside to the cities, in the metropolitan regions or interior, becoming mainly merchants, owning laundries, grocery stores, fairs, hairdressers, mechanical workshops, among others.

The presence of Japanese descendants in commercials, soap operas and films is rare and characterized by stereotypes, since "the beauty standard imposed in Brazil is still for characters played by white actors".

[69] Artists of Oriental origin complain that they only get cartoonish and stereotypical Japanese roles, such as market vendors, pastry chefs, tech enthusiasts, martial arts practitioners or sushi sellers.

According to the newspaper Folha de S. Paulo, in 2016, for the soap opera Sol Nascente, oriental actors who tested for the roles were dismissed and the broadcaster cast white artists to play characters of Japanese origin.

Members of the Japanese community accuse the broadcaster of racism and of fostering "yellowface", a practice similar to "blackface", when actors are cast to play roles of an ethnic group to which they do not belong.

[79] The Liberdade neighborhood, in the center of the capital of São Paulo, was the Japanese quarter of the city, although today it only maintains the characteristic shops and restaurants, with increasing influence of Chinese and Korean communities.

[41] The immigrants imported the first seeds from Singapore to Brazil, and with the prosperity leveraged by the Japanese, the population of the municipality more than tripled in twenty years, drawing the attention of many people in search of job opportunities, mostly migrants from Espírito Santo or the Northeast region.

[104] In 1930, Uyetsuka bought 1,500 hectares in Parintins, now called Vila Amazônia, and established the Escola Superior de Colonização do Japão (Nihon Koto Takushoku Gakko) to train specialists in colonization work.

[112] According to the newspaper Gazeta do Povo, "the common sense is that Japanese descendants are studious, disciplined, do well in school, pass the entrance exam more easily and, in most cases, have great affinities with mathematical careers".

The good performance of these students is due to the fact that the Japanese carry values such as discipline, respect for hierarchy, effort and dedication, as well as the belief that education is the best way to rise economically.

Other prominent Nikkei in Brazilian swimming are: Poliana Okimoto, Rogério Aoki Romero, Lucas Vinicius Yoko Salatta, Diogo Yabe, Tatiane Sakemi, Mariana Katsuno, Raquel Takaya, Cristiane Oda Nakama, Celina Endo, among others.

An example of Nikkei in Brazilian soccer is Sérgio Echigo, who played for Sport Club Corinthians Paulista and is considered the inventor of the dribbling called "elástico", which was later perfected and popularized by Roberto Rivellino.

According to IBGE data from the year 2000, about 63.9% of Japanese descendants in Brazil are Catholics, which represented the renunciation of religions commonly followed in Japan, such as Buddhism and Shintoism, in the name of greater integration into Brazilian society.