Internment of Japanese Canadians

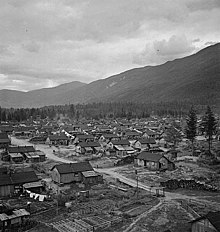

[2] From shortly after the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor until 1949, Japanese Canadians were stripped of their homes and businesses, then sent to internment camps and farms in British Columbia as well as in some other parts of Canada, mostly towards the interior.

[5][6] On September 22, 1988, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney delivered an apology, and the Canadian government announced a compensation package, one month after President Ronald Reagan made similar gestures in the United States following the internment of Japanese Americans.

Violette refuted this claim by stating that, while Japanese and Chinese immigrants did often have poor living conditions, both of the groups were hindered in their attempt to assimilate due to the difficulty they had in finding steady work at equal wages.

[20] After the riot, the League and other nativist groups used their influence to push the government into an arrangement similar to the United States' Gentlemen's Agreement, limiting the number of passports given to male Japanese immigrants to 400 per year.

On the home front, many businesses began hiring groups that had been underrepresented in the workforce (including women, Japanese immigrants, and Yugoslavian and Italian refugees who had fled to Canada during the war) to help fill the increasing demands of Britain and its allies overseas.

In contrast to rival groups' memberships consisting of mostly labourers, farmers, and fishermen, the Japan Society was primarily made up of wealthy white businessmen whose goal was to improve relations between the Japanese and Canadians both at home and abroad.

[33] On January 14, 1942, the federal government issued an order calling for the removal of male Japanese nationals between 18 and 45 years of age from a designated protected area of 100 miles (160 km) inland from the British Columbia Coast.

[36] This order in council granted the minister of justice the broad powers of removing people from any protected area in Canada, but was meant for Japanese Canadians on the Pacific coast in particular.

Mead attempted to slow down the process, allowing individuals and families more time to prepare by following the exact letter of the law, which required a complicated set of permissions from busy government ministers, rather than the spirit of quick removal it intended.

[47] For many Japanese Canadians, World War I provided an opportunity to prove their loyalty to Canada and their allies through military service in the hopes of gaining previously denied citizenship rights.

Various camps in the Lillooet area and in Christina Lake were formally "self-supporting projects" (also called "relocation centres") which housed selected middle- and upper-class families and others not deemed as much of a threat to public safety.

[78] The dispossession began in December 1941 with the seizure of fishing vessels owned by Japanese Canadians, and eventually led to the loss of homes, farms, businesses and smaller belongings such as family heirlooms.

Ian MacKenzie, the federal Minister of Pensions and National Health and British Columbia representative in Cabinet, was a political advocate for the dispossession of the property of Japanese Canadians.

In a very public move on behalf of the Department of Fisheries in British Columbia, it was recommended that in the future Japanese Canadians should never again receive more fishing licences than they had in 1919 and also that every year thereafter that number be reduced.

The federal government also got involved in 1926, when the House of Commons' Standing Committee on Fisheries put forward suggestions that the number of fishing licences issued to Japanese Canadians be reduced by ten percent a year, until they were entirely removed from the industry by 1937.

In Maple Ridge and Pitt Meadows, officials described that "it appears to be just the love of destruction which has made the thieves go through the buildings…" The Marpole-Richmond Review reported that, despite attempts to remove valuable items from the Steveston Buddhist Temple, looting had resulted in "numbers of cans in which have been deposited the white ashes of cremated former citizens of Steveston, have had their seals broken and their contents scattered over the floor…"[92] As a result, officials sought to warehouse many of the belongings of Japanese Canadians.

[94] As was common in his time, he held racial bias and believed skin colour determined loyalty, he once said "the only way the Yellow Race can obtain their place in the Sun is by winning the war.

[94] On January 11, 1943, a meeting of cabinet ministers (attended by Ian Alistair Mackenzie, Norman McLarty, Thomas Crerar, and Humphrey Mitchell) made the decision to permit the sale of Japanese Canadian owned property, which had been previously seized.

In 1944, Toyo Takahashi wrote to the Custodian, explaining that when she and her husband moved into 42 Gorge Road, Victoria they spent over ten years of labour and hard work cultivating a garden of rare and exotic plants that won a horticultural award and was visited by the Queen in 1937.

In 1947, due to an upcoming royal commission, Frank Shears reviewed the letters for the legal representatives of the Crown and relayed that the basis of protest fell with two distinct spheres, tangible, or monetary and intangible, beyond money.

The opposing lawyer, Fredrick Percy Varcoe, Deputy Minister of Justice, argued in front of Judge Joseph Thorarinn Thorson that the sales followed from the "emergency of war".

Without addressing the larger harms of the dispossession of Japanese Canadians, stated that "the custodian could neither be characterized as the Crown nor its servant"; therefore, the case ended before it began since the litigants had sued the wrong entity.

In June 1947, the Public Accounts Committee recommended that a commission be struck to examine the claims of Japanese Canadians living in Canada for losses resulting from receiving less than the fair market value of their property.

[109] After the report was released, the CCJC and National Japanese Canadian Citizens' Association wanted to push for further compensation, however, when claimants accepted their Bird Commission reimbursements, they had to sign a form agreeing that they would not press any further claims.

Officials created a questionnaire to distinguish "loyal" from "disloyal" Japanese Canadians and gave internees the choice to move east of the Rockies immediately or be "repatriated" to Japan at the end of the war.

[112] When news of Japan's surrender in August 1945 reached the internment camps, thousands balked at the idea of resettling in the war-torn country and attempted to revoke their applications for repatriation.

[112] Several Japanese Canadians who resettled in the east wrote letters back to those still in British Columbia about the harsh labour conditions in the fields of Ontario and the prejudiced attitudes they would encounter.

In 1983, the NAJC mounted a major campaign for redress which demanded, among other things, a formal government apology, individual compensation, and the abolition of the War Measures Act.

[87] On September 22, 1988, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney delivered an apology, and the Canadian government announced a compensation package, one month after President Ronald Reagan made similar gestures in the United States.

Writer Joy Kogawa is the most famous and culturally prominent chronicler of the internment of Japanese Canadians, having written about the period in works including the novels Obasan and Itsuka, and the augmented reality application East of the Rockies.