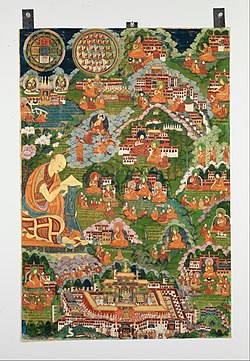

Je Tsongkhapa

According to Tsongkhapa, meditation must be paired with rigorous reasoning in order "to push the mind and precipitate a breakthrough in cognitive fluency and insight.

[10] With a Mongolian father and a Tibetan mother, Tsongkhapa was born into a nomadic family in the walled city of Tsongkha in Amdo, Tibet (present-day Haidong and Xining, Qinghai) in 1357.

[18] During his early years, Tsongkhapa also composed a few original works, including the Golden Garland (Wylie: legs bshad gser phreng), a commentary on the Abhisamayālaṃkāra from the perspective of the Yogācāra-svātantrika-madhyamaka tradition of Śāntarakṣita which also attempts to refute the shentong views of Dolpopa (1292–1361).

According to Garfield:[20]the major philosophical texts composed in the remaining twenty years of his life develop with great precision and sophistication the view he developed during this long retreat period and reflect his realization that while Madhyamaka philosophy involves a relentlessly negative dialectic — a sustained critique both of reification and of nihilism and a rejection of all concepts of essence—the other side of that dialectic is an affirmation of conventional reality, of dependent origination, and of the identity of the two truths, suggesting a positive view of the nature of reality as well.In 1409, Tsongkhapa worked on a project to renovate the Jokhang Temple, the main temple in Lhasa.

"[29] After Tsongkhapa's death, his disciples worked to spread his teachings and the Gelug school grew rapidly across the Tibetan plateau, founding or converting numerous monasteries.

[40] According to Jinpa, the correct object of negation for Tsongkhapa is "our innate apprehension of self-existence" which refers to how even our normal ways of perceiving the world "are effected by a belief in some kind of intrinsic existence of things and events".

[40] Jinpa also writes that the second major aspect of Tsongkhapa's philosophical project "entails developing a systematic theory of reality in the aftermath of an absolute rejection of intrinsic existence".

[61][60] In his works, Tsongkhapa takes pains to refute an alternative interpretation of emptiness which was promoted by the Tibetan philosopher Dolpopa Sherab Gyaltsen (1292–1361).

[65] In this view, things do exist in a conventional and nominal sense as conceptual imputations (rtog pas btags tsam) which are dependent upon a relationship with a knowing and designating mind.

[67][68] Tsongkhapa cites numerous passages from Nagarjuna which show that emptiness (the lack of intrinsic nature) and dependent origination (the fact that all dharmas arise based on causes and conditions) ultimately have the same intent and meaning and thus they are two ways of discussing one single reality.

[78] Sakya philosophers like Gorampa and his supporters held that madhyamaka analysis rejects all conventional phenomena (which he calls "false appearances" and sees as conceptually produced) and so, tables and persons are no more real than dreams or Santa Claus.

[68] For Tsongkhapa, it was not enough to just argue for the emptiness of all phenomena (the ultimate truth), madhyamaka also needed proper epistemic instruments or sources of knowledge (Tib.

[64] As Newland explains, each one of these epistemic points of view provides a different lens or perspective on reality, which Tsongkhapa illustrates by discussing how "we do not see sounds no matter how carefully we look."

Tsongkhapa argued that the svātantrika approach holds that one had to posit autonomous syllogisms (svatantrānumāna) in order to defend madhyamaka and that this insistence implies that phenomena (dharmas) or at least logic itself, has intrinsic nature (svabhava) conventionally.

[116] Jinpa notes that Tsongkhapa interprets the madhyamaka argument called 'diamond splinters' (rdo rje gzegs ma), which refutes the intrinsic arising of dharmas, in a similar manner.

pramāṇa) is central to the madhyamaka project, since he thinks that prāsaṅgika-madhyamikas make use of reasoning in order to establish their view of the lack of intrinsic nature conventionally.

However, he agrees that this teaching may be of provisional use for some individuals (since it was taught by the Buddha in some sutras) who hold to a lower view, are not able to fully understand emptiness and have a "fear of annihilation".

[128] Tsongkhapa also rejects Buddhist idealism (which was associated with the Yogācāra school and various Tibetan madhyamaka authors) and thus affirms the conventional existence of an external world (like Bhaviveka).

[133] For Tsongkhapa, only the madhyamaka view of Nagarjuna (as understood by prāsaṅgikas like Aryadeva, Buddhapalita, Candrakīrti and Shantideva) is a definitive interpretation of the final intent of the Buddha.

[104] However, because of the Buddha's bodhicitta, he explains the teaching in a wide variety of (neyartha) ways, all of which are ultimately based in and lead to the final insight into emptiness.

[135] The philosophical critique of Tsongkhapa was later continued by a trio of Sakya school thinkers: Taktsang Lotsawa, Gorampa, and Shākya Chokden, all followers of Rongton.

[28][30] According to Jinpa, Taktsang's critique focuses on "Tsongkhapa's insistence on the need to maintain a robust notion of conventional truth grounded in some verifiable criteria of validity".

Tsongkhapa's presentation generally follows the classic Kadam Lamrim system, which is divided into three main scopes or motivations (modest, medium and higher i.e.

Regarding the perfection of wisdom (prajñāpāramitā), Tsongkhapa emphasizes the importance of reasoning, analytical investigation as well as the close study and contemplation of the Buddhist scriptures.

To develop the wisdom to see through this habit requires using reasoned analysis or analytical investigation (so sor rtog pa) to arrive at the right view of emptiness (the lack of intrinsic nature).

[5][136][note 17] Establishing the correct view of emptiness initially requires us to 'identify the object of negation', which according to Tsongkhapa (quoting Chandrakirti) is "a consciousness that superimposes an essence of things".

[144][145][7] This is because, for Tsongkhapa, the "I" or self is accepted as nominally existing in a dependent and conventional way, while the object to be negated is the inner fiction of intrinsic nature which is "erroneously reified" by our cognition.

[146][147][note 18][148] Tsongkhapa explains this mistaken inner reification which is to be negated as "a natural belief [a naive, normal, pre-philosophical way of seeing the world], which leads us to perceive things and events as possessing some kind of intrinsic existence and identity".

[163] As such, Tsongkhapa sees Secret Mantra as being a subset of Mahāyāna Buddhism, and thus it also requires bodhicitta and insight into emptiness (through vipaśyanā meditation) as a foundation.

As Tsongkhapa states in A Lamp to Illuminate the Five Stages:for those who enter the Vajra Vehicle, it is necessary to search for an understanding of the view that has insight into the no-self emptiness and then to meditate upon its significance in order to abandon holding to reality, the root of samsara.