Jean Ross

Her escapades inspired the heroine in Christopher Isherwood's 1937 novella Sally Bowles which was later collected in Goodbye to Berlin,[10][11] a work cited by literary critics as deftly capturing the hedonistic nihilism of the Weimar era and later adapted into the stage musical Cabaret.

[15][16] For the remainder of her life, Ross believed the public association of herself with the naïve and apolitical character of Sally Bowles occluded her lifelong work as a professional writer and political activist.

[18] In addition to inspiring the character Sally Bowles,[19] Ross is credited by the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and other sources as the muse for lyricist Eric Maschwitz's jazz standard "These Foolish Things (Remind Me of You)", one of the 20th century's most enduring love songs.

[26] Using a trust stipend provided by her grandfather Charles Caudwell, who was an affluent industrialist and landowner,[25] the teenage Ross returned to England and enrolled in the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA), London.

[26] In 1930, at nineteen years of age, Ross and fellow Egyptian-born Hungarian actor Marika Rökk obtained cinematic roles portraying a harem houri in director Monty Banks' Why Sailors Leave Home, an early sound comedy that was filmed in London.

[27] Disappointed with their small roles, she and Rökk heard rumours about ample job opportunities for aspiring actors in the Weimar Republic of Germany and set off with great expectations for Berlin.

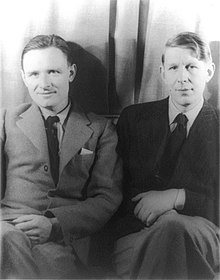

[b][30][35] By late 1931, Ross had moved to Schöneberg, Berlin, where she shared modest lodgings in Fräulein Meta Thurau's flat at Nollendorfstraße 17 with English writer Christopher Isherwood, whom she had met in October 1930 or early 1931.

[c][37][38] Isherwood, who was an apprentice novelist, was politically ambivalent about the rise of fascism and had moved to Berlin in order to avail himself of boy prostitutes and to enjoy the city's orgiastic Jazz Age cabarets.

[30][45][46] A contemporary portrait of the 19-year-old Ross appears in Isherwood's Goodbye to Berlin when the narrator first encounters the "divinely decadent" Sally Bowles:[47][48] I noticed that her fingernails were painted emerald green, a colour unfortunately chosen, for it called attention to her hands, which were much stained by cigarette smoking and as dirty as a little girl's.

[51] By day, Ross was a fashion model for popular magazines,[26] and by night, she was a bohemian chanteuse singing in the nearby cabarets located along the Kurfürstendamm avenue, an entertainment-vice district that was selected for future destruction by Nazi politician Joseph Goebbels in his 1928 journal.

[64][65] Meanwhile, Ross entered into a variety of heterosexual liaisons, including one with musician Götz von Eick,[66] who later became an actor under the stage name Peter van Eyck and starred in Henri-Georges Clouzot's The Wages of Fear.

My mother [Jean Ross], on the other hand, was at least talented enough as an actress to be cast as Anitra in Max Reinhardt's production of Peer Gynt and competent enough as a writer to earn her living, not long afterwards, as a scenario-writer and journalist.

[93] Meanwhile, she continued her career as an aspiring thespian, appearing in theatrical productions at the Gate Theatre Studio that were directed by Peter Godfrey and, in need of money, she modelled the latest Paris fashions by French designer Jean Patou in Tatler magazine.

[113] Despite its limited personnel and modest funds, the League produced newsreels, taught seminars on working-class film criticism, organised protests against "reactionary pictures", and screened the latest blockbusters of Soviet Russia to cadres of like-minded cineastes.

[117] Between 1935 and 1936, Ross worked as a film critic for the Communist newspaper Daily Worker using the alias Peter Porcupine,[118][119] which she presumably adopted as a homage to radical English pamphleteer William Cobbett, who had used the same pseudonym.

[76] According to Spender, their quartet of friends viewed such films as Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Fritz Lang's Metropolis, and Josef von Sternberg's The Blue Angel.

Pabst's Comradeship as well as "Russian films in which photography created poetic images of labour and industry", which is exemplified in Ten Days That Shook the World and The Battleship Potemkin.

[121]In her film criticism, Ross stated that "the workers in the Soviet Union [had] introduced to the world" new variations of this art form with "the electrifying strength and vitality and freedom of a victorious working class".

[k][123][124] As the first English volunteer to enlist against Francisco Franco's forces, Cornford had just returned from the Aragon front, where he had served with the POUM militia near Saragossa, and fought in the early battles near Perdiguera and Huesca.

[143] During Ross' tenure in the organisation, the Espagne News-Agency was accused by journalist George Orwell of being a Stalinist apparatus that disseminated false propaganda to undermine anti-Stalinist factions on the Republican side of the Spanish Civil War.

[147] Ross' fellow Comintern propagandists included Hungarian journalist Arthur Koestler,[148] Willy Forrest, Mildred Bennett of the Moscow Daily News, and Claud Cockburn.

[149] While covering the Spanish Civil War for the Daily Worker in 1936, Cockburn had joined the elite Fifth Regiment of the left-wing Republicanos battling the right-wing Nacionales and, when not fighting, he gave sympathetic coverage to the Communist Party.

Among the other foreign correspondents in besieged Madrid were Herbert Matthews of The New York Times,[156] Ernest Hemingway of the North American Newspaper Alliance,[157] Henry Tilton Gorrell of United Press International,[156] and Martha Gellhorn of Collier's,[156] as well as Josephine Herbst.

[158] In early 1937, as the civil war progressed, Ross, her friend Richard Mowrer of The Chicago Daily News—the step-son of Ernest Hemingway's first wife Hadley Richardson[r]—and their guide Constancia de la Mora travelled to Andalusia to report on the southern front.

[163] Following her interview with Colonel José Morales, the convoy in which Ross was travelling faced recurrent enemy fire and later, during the evening, was bombed by a fascist air patrol.

[174] Much like Ross, Mangeot had been an apolitical bohemian in her youth and transformed with age into a devout Stalinist who sold the Daily Worker and was an active member of various left-wing circles.

[178] While Sarah was at Oxford, Ross continued to engage in political activities including protesting nuclear weapons, boycotting apartheid South Africa, and opposing the Vietnam War.

[25] Sommerfield recalled: She seemed burned out ... with bruise marks under her eyes and lines of discontent round her mouth; her once beautiful black hair looked dead, and she wore too much make-up, carelessly applied.

In a diary entry for 24 April 1970,[177] Isherwood recounted their final reunion in London: I had lunch with Jean Ross and her daughter Sarah [Caudwell], and three of their friends at a little restaurant in Chancery Lane.

[18] Ross believed the character's political indifference more closely resembled Isherwood or his gay friends,[182] many of whom "fluttered around town exclaiming how sexy the storm troopers looked in their uniforms".