Jean de Carrouges

The combat was decreed in 1386 to contest charges of rape Carrouges had brought against his neighbour and erstwhile friend Jacques Le Gris on behalf of his wife Marguerite.

Described in the chronicles as a rash and temperamental man, Carrouges was also a fierce and brave warrior whose death in battle came after a forty-year military career in which he served in Normandy, Scotland and Hungary with distinction and success.

Shortly after their wedding, Jeanne gave birth to a son, whose godfather was a neighbour and close friend of de Carrouges, Squire Jacques Le Gris.

While Carrouges was overlooked, Le Gris was rewarded for service to the Count, inheriting his father's lordship of the castle at Exmes and being granted a newly purchased estate at Aunou-le-Faucon.

[8] With this force, under the overall command of King Charles V, Carrouges distinguished himself in minor actions against the English in Beuzeville, Carentan, and Coutances in a five-month campaign, during which over half his retinue were killed in battle or by disease.

The valuable estate of Aunou-le-Faucon, given to his rival Jacques Le Gris two years earlier, had been formerly owned by Carrouges' father-in-law, Robert de Thibouville, and had been bought by Count Pierre for 8,000 French livres in 1377.

[10] The case dragged on for some months until ultimately Count Pierre was forced to visit his cousin King Charles VI to confirm his ownership of the land officially, as well as his right to give it to whomever of the followers he chose.

[14] A few months after this meeting, in March 1385, Carrouges attempted to increase his family wealth through military means, by joining the army of Jean de Vienne for an expedition sailing to Edinburgh.

[citation needed] On arrival in Scotland, much time was spent gathering Scottish troops together for the campaign on England, and the French were delayed for some months collecting supplies.

Realising that his force was outnumbered and without food or help, Vienne took the army south, rounding the English on the night of 10 August and reentering Northumberland for further looting, attacking Carlisle but being unable to break through its walls.

[19] Despite being in poor health on his return from Scotland, Carrouges had business in Paris and in January 1386 he travelled there to collect his wages for the previous year's campaign, leaving his wife with his mother at the village of Capomesnil.

According to Marguerite, Louvel then made inquiries about a loan he owed Jean de Carrouges before suddenly announcing that Jacques Le Gris was outside the door and insisted on seeing her.

[28] A few days after his arrival in Paris, Carrouges was presented to the King at the Château de Vincennes in order to make the first official appeal in the lengthy trial process.

[29] On 9 July 1386, the second stage in the legal process began when both Carrouges and Le Gris, with their followers, presented themselves before the Parlement of Paris at the Palais de Justice to issue the formal challenge.

The declarations were pronounced in front of the King, his brother Louis of Valois and the entire Parlement, who decided to initially hear the case as an ordinary criminal one and defer their decision on whether to permit the judicial duel until both sides had given testimony.

[31] Following the declarations a number of high-ranking noblemen stepped forward to act as seconds in the duel for both men, including Waleran of Saint-Pol for Carrouges and Philip of Artois, Count of Eu for Le Gris.

Marguerite was by this time visibly pregnant, although medieval medical knowledge claimed that children could not be conceived as a result of rape and her condition, therefore, was determined to have no bearing on the case.

[33] Adam Louvel and at least one of Marguerite's maidservants also gave evidence and, as was the custom of the day for people of low birth, they were tortured to test the veracity of their testimony.

[36] In his statement, Le Gris painted a picture of a man driven wild with anger and jealousy who sought to restore his family fortune by concocting false accusations against his most significant rival.

[36] A rebuttal from Carrouges emphasised the shame the trial had brought to his family as a reason against its invention and offered a counter-demonstration of horsemanship indicating that the suggested 80-kilometre (50-mile) round trip was possible even if Le Gris' alibi were true.

[37] Le Gris' alibi was compromised some days later when the man providing it, a squire named Jean Beloteau, was arrested for committing rape in Paris during the trial.

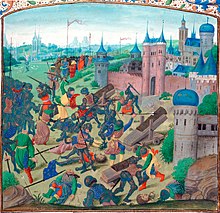

As judicial duels were now so rare, no established battleground had been set aside, and a jousting arena at the Abbey of Saint-Martin-des-Champs north of the city agreed to host the combat.

[38] Both Carrouges and Le Gris endured bouts of illness in the weeks following the verdict but recovered with the aid of their families and supporters, who had joined the hundreds of people flocking to the city from nearby regions to witness the fight.

[41] As the field was cleared, silence descended on the arena following the King's instructions that anybody who interfered in the duel would be executed and that anyone who shouted or verbally interrupted the combat would lose a hand.

Le Gris' heavy armour prevented him from regaining his feet and Carrouges repeatedly stabbed at his floored opponent, his blows denting but not puncturing the thick plate steel.

In this mission he was second in command to Jean de Boucicaut, a Marshal of France and famous soldier, indicating the elevated social position Carrouges enjoyed following the duel.

[50] The army crossed Central Europe, united with the Hungarians and marched south, burning the city of Vidin, and massacring the inhabitants before following the course of the Danube southeast, cutting a swathe of destruction through the Ottoman territory.

The crusader army moved to confront him on 24 September, but poor discipline and fractured leadership between the national factions resulted in a premature assault by the French force against the bluffs controlled by Ottoman troops.

[6] This story, which The Last Duel author Eric Jager claims is "without basis", was subsequently repeated in many later sources, particularly as proof for the great miscarriage of justice of the event and the tradition of trial-by-combat.

[58] In the 20th century, other authors have studied the case, the most recent being in the book The Last Duel: A True Story of Trial by Combat in Medieval France in 2004, by Eric Jager, a professor of English Literature at UCLA.