Jesu, meine Freude, BWV 227

The text of the motet's even-numbered movements is taken from the eighth chapter of the Epistle to the Romans, a passage that influenced key Lutheran teachings.

The hymn, written in the first person with a focus on an emotional bond with Jesus, forms a contrasting expansion of the doctrinal biblical text.

Unique in its complex symmetrical structure juxtaposing hymn and biblical texts, and with movements featuring a variety of styles and vocal textures, the motet has been regarded as one of Bach's greatest achievements in the genre.

In this context, motets are choral compositions, mostly with a number of independent voices exceeding that of a standard SATB choir, and with German text from the Luther Bible and Lutheran hymns, sometimes in combination.

According to Philipp Spitta, Bach's 19th-century biographer, Johann Michael Bach's motet Halt, was du hast [choralwiki], ABA I, 10, which contains a setting of the "Jesu, meine Freude" chorale, may have been on Johann Sebastian's mind when he composed his motet named after the chorale, in E minor like his relative's.

[1][2] In Bach's time, the Lutheran liturgical calendar of the place where he lived indicated the occasions for which music was required in church services.

[9] Exceptional compositions with five-part movements can be found in the Magnificat, written in 1723 at the beginning of Bach's tenure in Leipzig, and the Mass in B minor, compiled towards the end of his life.

[12][14] The text of Jesu, meine Freude is compiled from two sources: a 1653 hymn of the same name with words by Johann Franck, and Bible verses from Paul's Epistle to the Romans, 8:1–2 and 9–11.

[15] The hymn is written in the first person and deals with a believer's bond to Jesus who is addressed as a helper in physical and spiritual distress, and therefore a reason for joy.

[16] the melody is built from one motif, the beginning descent of a fifth (catabasis), with the word "Jesu" as the high note, which is immediately inverted (anabasis [de]).

[34] According to Bach scholar Richard D. P. Jones, several movements of Jesu, meine Freude show a style too advanced to have been written in 1723.

[12][30][36] Jesu, meine Freude is structured in eleven movements, with text alternating between a chorale stanza and a passage from the Epistle.

The last movement, the chorale's sixth stanza, has the same music, creating a frame that encloses the whole work:[35] The second movement begins the excerpts from Romans 8, setting verse 1, "Es ist nun nichts Verdammliches an denen, die in Christo Jesu sind" (There is therefore now no condemnation to them which are in Christ Jesus).

[44] The beginning of the text is rendered in "rhetorical" homophony:[35] Bach accented the word "nichts" (nothing), repeating it twice, with long rests and echo dynamics.

[35] The fourth movement sets the second verse from Romans 8, "Denn das Gesetz des Geistes, der da lebendig machet in Christo Jesu, hat mich frei gemacht von dem Gesetz der Sünde und des Todes" (For the law of the Spirit of life in Christ Jesus hath made me free from the law of sin and death.).

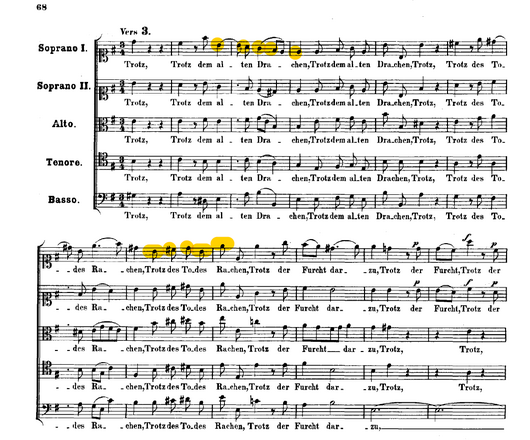

[35][51] Five voices take part in a dramatic illustration as they depict defiance by standing firmly and singing, often in powerful unison.

[53]The central sixth movement sets verse 9 from Romans 8, "Ihr aber seid nicht fleischlich, sondern geistlich" (But ye are not in the flesh, but in the Spirit).

[35] It is a double fugue, with a first theme for the first line, another for the second, "so anders Gottes Geist in euch wohnet" (since the Spirit of God lives otherwise in you), before both of them are combined in various ways, parallel and in stretti.

[45] The seventh movement is a four-part setting of the fourth stanza of the hymn, "Weg mit allen Schätzen" (Away with all treasures).

[15][55] While the soprano sings the chorale melody, the lower voices intensify the gesture; "weg" (away) is repeated several times in fast succession.

[45] The ninth movement is a setting of the fifth stanza of the hymn, "Gute Nacht, o Wesen, das die Welt erlesen" (Good night, existence that cherishes the world).

[15][58] For the rejection of everything earthly, Bach composed a chorale fantasia, with the cantus firmus in the alto voice and repetition of "Gute Nacht" in the two sopranos and the tenor.

[60] The chorale melody used in the movement is slightly different from the one in the other settings within the motet,[61] a version which Bach used mostly in his earlier time in Weimar and before.

[53] Jones, however, found that the "bewitchingly lyrical setting" matched compositions from the mid-1720s in Leipzig,[62] comparing the music to the Sarabande from the Partita No.

[63] The motet ends with the same four-part setting as the first movement, with the last stanza of the hymn as lyrics, "Weicht, ihr Trauergeister" (Flee, you mournful spirits).

[15][41][64] The final line repeats the beginning on the same melody: "Dennoch bleibst du auch im Leide, / Jesu, meine Freude" (You stay with me even in sorrow, / Jesus, my joy).

[15] Jesu, meine Freude is unique in Bach's work in its complex symmetrical structure, which juxtaposes hymn and Bible text.

[65][66] Wolff summarised: This diversified structure of five-, four-, and three-part movements, with shifting configurations of voices and a highly interpretive word-tone relationship throughout, wisely and sensibly combines choral exercise with theological education.

[79] The optimum size of the choir in this work continues to be discussed to this day, for example in reviews of Philippe Herreweghe's one voice per part recordings of 1985 and 2010.