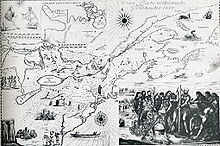

Jesuit Missions amongst the Huron

In other colonies, such as in Latin America, the Jesuit missions had found a more eager and receptive audience to Christianity, the result of a chaotic atmosphere of violence and conquest.

[1] Nevertheless, the French missionary settlements were integral to maintaining political, economic, and military ties with the Huron and other native peoples in the region.

But the Huron mainly practiced a form of sedentary agriculture, which appealed to the French, who believed that cultivating the land and making it productive was a sign of civilization.

[9] The Jesuit missionaries who came to New France in the seventeenth century aimed to both convert native peoples such as the Huron to Christianity and also to instill European values within them.

[11] Compared to other native populations in the region such as the hunter-gatherer Innu or Mi’kmaq peoples, the Huron already fit in relatively well with the Jesuits’ ideas of stable societies.

[12] Nonetheless, the Jesuits often found it hard to bridge the cultural divide and their religious and social conversion efforts often met with stiff resistance from the Huron.

War and violent conflict between tribes, on the other hand, helped create a far more receptive audience to Christianity and increased the Jesuits' potential for successful conversion.

[16] The type of Catholicism that the Jesuits preached to Huron was radicalized by decades of violent conflict in France and could be intolerant of non-Catholic spirituality.

[17] This Catholicism demanded an all-or-nothing commitment from converts, which meant that the Huron were sometimes forced to choose between their Christian faith and their traditional spiritual beliefs, family structures, and community ties.

Others—though curious about the European faith—were prevented from baptism by the Jesuits out of the concern that these Huron were dangerously combining traditional practices with Christian concepts.

They feared the consequence of converts breaking all their ritual, familial, and communal ties, and so, began to actively oppose the missionary program.

One of them separates itself from the body at death yet remains in the cemetery until the Feast of the Dead, after which it either changes into a dove, or according to a common belief, it goes away at once to the village of souls.

Within the religious context, the Jesuits had found themselves in competition with native spiritual leaders, and so often presented themselves as shamans capable of influencing human health through prayer.

Aboriginal conceptions of shamanistic power were ambivalent and it was believed that shamans were capable of doing both good and ill. As a result, the Huron easily attributed their boons as well as their problems of disease, illness, and death to the Jesuit presence.

The Jesuits frequently performed surreptitious baptisms on ailing and dying infants, in the belief that these children would be sent to heaven since they did not have the time to sin.

[26] Resistance to the Jesuit missions grew as the Huron took repeated blows to their population and their political, social, cultural, and religious heritage.

The Jesuits had initially envisioned a relatively easy and efficient conversion of native people who supposedly lacked religion and would therefore eagerly adopt Catholicism.

Combined with the harsh Canadian environment and the threat of physical violence against the missionaries at the hands of native peoples grew, the Jesuits began interpreting their difficulties of "carrying the cross" from a metaphorical to an increasingly literal level as preparation for their eventual martyrdom.

Thus, the contact between the Huron and Jesuits enacted major changes in the spiritual, political, cultural, and religious lives of both natives and Europeans in North America.

The unstable peace came to an end in the summer of 1647 when a diplomatic mission headed by Jesuit Father Isaac Jogues and Jean de Lalande to Mohawk territory (one of the five Iroquois nations) was accused of treachery and evil magic.

Between 1648-1649, Huron settlements with a Jesuit presence, such as the towns of St. Joseph under Father Antoine Daniel, the villages of St. Ignace and St. Louis, as well as the French fort of Ste.

Jesuits were among those captured, tortured, and killed in these attacks; from the missionary perspective, individuals such as Jean de Brébeuf died as martyrs.

One party of Huron people had escaped to Île St. Joseph but with their food supplies destroyed, they soon faced starvation; those who left the island in search of game, risked encountering Iroquois raiders who hunted down the hunters "with a ferocity that stunned Jesuit observers.