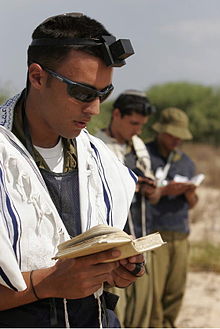

Jewish prayer

According to tradition, many of the current standard prayers were composed by the sages of the Great Assembly in the early Second Temple period (516 BCE – 70 CE).

The main structure of the modern prayer service was fixed in the Tannaic era (1st–2nd centuries CE), with some additions and the exact text of blessings coming later.

Synagogues may designate or employ a professional or lay hazzan (cantor) for the purpose of leading the congregation in prayer, especially on Shabbat or holy holidays.

[8] He rules that the commandment is fulfilled by any prayer at any time in the day, not a specific text; and thus is not time-dependent, and is mandatory for both Jewish men and women.

[9] Modern scholarship dating from the Wissenschaft des Judentums movement of 19th-century Germany, as well as textual analysis influenced by the 20th-century discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, suggests that dating from the Second Temple period there existed "liturgical formulations of a communal nature designated for particular occasions and conducted in a centre totally independent of Jerusalem and the Temple, making use of terminology and theological concepts that were later to become dominant in Jewish and, in some cases, Christian prayer.

[15] The Amidah (or Shemoneh Esreh) prayer is traditionally ascribed to the Great Assembly (in the time of Ezra, near the end of the biblical period), though other sources suggest it was established by Simeon HaPakoli in the late 1st century.

Despite this, the tradition of most Ashkenazi Orthodox synagogues is to use Hebrew for all except a small number of prayers, including Kaddish and Yekum Purkan in Aramaic, and Gott Fun Avraham, which was written in Yiddish.

In traditionalist congregations the liturgy can be almost identical to that of Orthodox Judaism, almost entirely in Hebrew (and Aramaic), with a few minor exceptions, including excision of a study session on Temple sacrifices, and modifications of prayers for the restoration of the sacrificial system.

There are some changes for doctrinal reasons, including egalitarian language, fewer references to restoring sacrifices in the Temple in Jerusalem, and an option to eliminate special roles for Kohanim and Levites.

Doctrinal revisions generally include revising or omitting references to traditional doctrines such as bodily resurrection, a personal Jewish Messiah, and other elements of traditional Jewish eschatology, Divine revelation of the Torah at Mount Sinai, angels, conceptions of reward and punishment, and other personal miraculous and supernatural elements.

In Jewish philosophy and in Rabbinic literature, it is noted that the Hebrew verb for prayer—hitpallel (התפלל)—is in fact the reflexive form of palal (פלל), to judge.

Kabbalah (esoteric Jewish mysticism) uses a series of kavanot, directions of intent, to specify the path the prayer ascends in the dialogue with God, to increase its chances of being answered favorably.

Kabbalism ascribes a higher meaning to the purpose of prayer, which is no less than affecting the very fabric of reality itself, restructuring and repairing the universe in a real fashion.

This approach has been taken by the Chassidei Ashkenaz (German pietists of the Middle-Ages), the Zohar, the Arizal's Kabbalist tradition, the Ramchal, most of Hassidism, the Vilna Gaon and Jacob Emden.

[24] The Baal Shem Tov's great-grandson, Rebbe Nachman of Breslov, particularly emphasized speaking to God in one's own words, which he called Hitbodedut (self-seclusion) and advised setting aside an hour to do this every day.

Another Aramaic derivation, proposed by Avigdor Chaikin, cites the Talmudic phrase, "ka davai lamizrach", 'gazing wistfully to the east'.

In recent decades, some communities have adopted the practice to sing the piyut Yedid Nefesh before (or occasionally after) the Kabbalat Shabbat prayers.

In modern times the Kabbalat Shabbat has been set to music by many composers including: Robert Strassburg[53] and Samuel Adler[54] The Shema section of the Friday night service varies in some details from the weekday services—mainly in the different ending of the Hashkivenu prayer and the omission of Baruch HaShem Le'Olam prayer in those traditions where this section is otherwise recited.

In many communities, the rabbi (or a learned member of the congregation) delivers a sermon at the very end of Shacharit and before Mussaf, usually on the topic of the Torah reading.

In Orthodox Judaism this is followed by a reading from the Talmud on the incense offering called Pittum Haketoreth and daily psalms that used to be recited in the Temple in Jerusalem.

According to (Ashkenazi) Magen Avraham[63] and more recently (Sephardi) Rabbi Ovadia Yosef,[64] women are only required to pray once a day, in any form they choose, so long as the prayer contains praise of (brakhot), requests to (bakashot), and thanks of (hodot) God.

Haredi and the vast majority of Modern Orthodox Judaism has a blanket prohibition on women leading public congregational prayers.

Many of those who do not accept this reasoning point to kol isha, the tradition that prohibits a man from hearing a woman other than his wife or close blood relative sing.

The first Orthodox Jewish women's prayer group was created on the holiday of Simhat Torah at Lincoln Square Synagogue in Manhattan in the late 1960s.

[71] These practices are also unheard of in the Hareidi world In most divisions of Judaism boys prior to bar mitzvah cannot act as a Chazzen for prayer services that contain devarim sheb'kidusha, i.e. Kaddish, Barechu, the amida, etc., or receive an aliya or chant the Torah for the congregation.

Since Kabbalat Shabbat and Pesukei D'zimra do not technically require a chazzan at all, it is possible for a boy prior to bar mitzvah to lead these services.

Under the Moroccan, Yemenite, and Mizrachi customs, a boy prior to bar mitzvah may lead certain prayers, read the Torah, and have an aliyah.

In traditionalist congregations the liturgy can be almost identical to that of Orthodox Judaism, almost entirely in Hebrew (and Aramaic), with a few minor exceptions, including excision of a study session on Temple sacrifices, and modifications of prayers for the restoration of the sacrificial system.

There are some changes for doctrinal reasons, including egalitarian language, fewer references to restoring sacrifices in the Temple in Jerusalem, and an option to eliminate special roles for Kohanim and Levites.

Doctrinal revisions generally include revising or omitting references to traditional doctrines such as bodily resurrection, a personal Jewish Messiah, and other elements of traditional Jewish eschatology, Divine revelation of the Torah at Mount Sinai, angels, conceptions of reward and punishment, and other personal miraculous and supernatural elements.