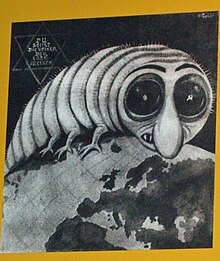

Jewish parasite

[2][3] The German theologian and philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803), an important representative of Weimar Classicism, wrote in the third part of his ideas on the philosophy of the history of mankind in 1791: "The people of God, to whom heaven itself once gave its fatherland, has been a parasitic plant on the tribes of other nations for millennia, almost since its creation; a race of clever negotiators almost all over the world who, despite all oppression, long nowhere for their own honour and home, nowhere for a fatherland".A very similar passage can also be found in the fourth part.

[6] The German literary scholar Klaus L. Berghahn believes that Herder's sympathy was only for ancient Judaism: On the other hand, he had, opposed the Jews their presence.

[7] The Polish Germanist Emil Adler, on the other hand, considers it possible - also in view of the positive remarks on Judaism a few pages before or after - that Herder only wanted to set an "apologetic counterweight": Also in other places of the ideas he had contrasted critical enlightenment formulations with conservative Orthodox thoughts and therefore weakened them in order not to endanger his position as General Superintendent of the Lutheran Church in Weimar.

[9] In 1804, the reviewer of an anti-Jewish work by the German Enlightenment writer Friedrich Buchholz (1768–1843) picked up on the metaphor of the Jew in the Neue allgemeine Deutsche Bibliothek as "a parasitic plant that incessantly clings to a noble bush, nourishes itself from the juice".

[10] In 1834, the metaphor was directed against Jewish emancipation in an article in the journal Der Canonische Wächter: The Jews would be “a true plague of the peoples parasitically surround them”.

It was adopted from the physiocracy of the 18th century, which called urban merchants and manufactory owners "class stérile" in contrast to the supposedly only productive farmers.

He relied here on the philosopher of religion Ernest Renan (1823–1893), who held the view that the Hebrew language was incapable of abstract conceptualization and therefore of metaphysics.

[22] When more and more Jews fled from Eastern Europe to Germany and Austria in the 1880s, the depiction of the Jewish parasite and disease vector became the topos of antisemitic literature.

If originally meanings from botany were added to it (as with Herder), it was increasingly associated with zoology or infectiology: Now one had to imagine leeches, lice, viruses or even vampires under "Jewish parasites", which would have to be fought ruthlessly.

[34] The Austrian political scientist Michael Ley, on the other hand, assumes that Lagarde strived for the annihilation of Jews; for him, it was in the sense of a redemption antisemitism "a necessary step on the way of salvation of the German people".

[40] A variant of antisemitic parasitology was offered by the völkisch writer Artur Dinter, who in 1917 developed the so-called impregnation theory in his novel Die Sünde gegen das Blut (The Sin Against the Blood), according to which Jews were also "pests on the German body of the people", meaning non-Jewish women who had once been pregnant by a Jew were no longer able to "give birth to children of their own race", even with a non-Jewish partner.

[44] In 1937, the antisemitic writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline (1864–1961), in his Bagatelles pour un massacre, published in Germany in 1938 under the title Die Judenverschwörung in Frankreich (The Jewish Conspiracy in France), took up the accusations of the early Socialists and denounced "the Jew" as "the most intransigent, most voracious, most corrosive parasite".

According to Bernhard Pörksen, such animal metaphors serve the attempt to "create disgust and lower inhibitions of Extermination"[51] According to the 2007 analysis by Albert Scherr and Barbara Schäuble, the antisemitic "topos of parasites, impurities and blood", to which the stereotype "Jewish parasite" can be attributed, is also taken up in media discourses as well as by contemporary young people in narratives and argumentations.

After the Iranian Revolution in 1979, wealthy Jews in the country were accused of exploiting their Muslim workers as "bloodsuckers" and transferring the profits for arms purchases to Israel.

[54] The Iranian television series Zahra's Blue Eyes, first broadcast in 2004, claims that Jews steal the organs of Palestinian children.

The Jewish organ recipients are portrayed as not viable without the body parts of their victims, which Klaus Holz and Michael Kiefer interpret as picking up the parasite stereotype.

[55] At the International Holocaust Cartoon Competition organized by the Iranian newspaper Hamshahri, a drawing was submitted in which Jews were portrayed as worms infesting an apple.

[56] On February 12, 2025, Elon Musk published an image of actor Sydney Sweeney on social media with the caption "Watching Trump slash federal programs knowing it doesn't affect you because you're not a member of the Parasite Class".

[61] Alexander Bein sees in the discourse of the "Jewish parasite", who understood his biologistic terminology not metaphorically but literally, one of the semantic causes of the Holocaust.

The Jews were equated with locusts: "The Jewish people are forced by their blood not to live from honest creative work, but from fraud and usury.

Also in 1927, a Nazi poster that advertised an event with Gregor Strasser, referred to the frequent objection that Jews were also human beings, and gave the cynical answer: "The flea is also an animal, though not a pleasant one".

[67] In the same year, the Nazi journalist Arno Schickedanz (1892–1945) unfolded the stereotype fin his scrip of Sozialparasitismus im Völkerleben (Social parasitism in peoples' lives).

His law is not to argue, but to conquer; not to serve values, but to exploit devaluation, according to which he can begin and from which he can never escape - as long as he exists"Reich Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels (1897–1945) expressed similar views in a speech on April 6, 1933: The Jews were "a completely foreign race" with "markedly parasitic characteristics".

[65] In a radio broadcast in January 1938, the Nazi Walter Frank raised the conflict with the "parasite" Judaism to a religious level: It could not be understood without classifying it in the world-historical process "in which God and Satan, creation and decomposition lie in eternal struggle"[69] Hitler himself depicted in a Reichstag speech on 26 April 1942 the globally perishable consequences of the Jews' alleged striving for world domination: "What then remains is the animal in man and a Jewish stratum that has been brought to power as a parasite, which in the end destroys its own breeding ground.

[71] The Nazi discourse on the "Jewish parasite" was supplemented by further equations of Jews with pathogens, rats or vermin, as can be seen in Fritz Hippler's propaganda film Der Ewige Jude from 1940.

This accusation had been taken up in the 20th century by antisemites such as the Thule Society and also by Hitler himself, who during the war against the Soviet Union took advantage of the impending extermination of "this plague" (meant was the alleged Jewish Bolshevism) as a grateful achievement.

[72] In May 1943, in a conversation with Goebbels, he picked up the stereotype once again and varied it by another pest: this time he equated the Jews with potato beetles, which one could also ask oneself why they existed at all.

[77] As late as 1944, posters were stuck in the General government showing rats in front of a star of David with the inscription: "Żydzi powracają wraz z bolszewizmen" (German: "Die Juden kehren mit dem Bolschewismus zurück").

[60] Zionists and "Halutzim", the pioneers of Jewish repopulation, mystified the soil and the handiwork with which it was cultivated: In a travelogue, Hugo Herrmann (1887–1940) described the almost liberating zeal of the previous "airmen, parasites, traders and hagglers" after their entry into Eretz Israel.

[80] The co-founder of the Zionist World Organization Max Nordau (1849–1923) formulated the ideal of the "muscle Jew", whereby he did not fall back on the parasite metaphor, but according to the Austrian historian Gabriele Anderl his statements and those of other Zionist theorists can be understood "from today's point of view also as an internalization of the antisemitic caricature of the Jew as unproductive parasite".