Jews in the civil rights movement

[3] Prominent Jewish leaders such as Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel and Jack Greenberg marched alongside figures like Martin Luther King Jr. and contributed significantly to landmark legal victories.

[4] While this period is sometimes remembered as a "golden age" of African American–Jewish relations, modern scholars point out that there were still disagreements and tensions between Blacks and Jews at the time.

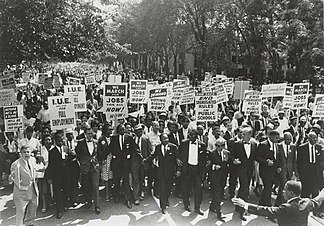

[16] Among the American Jewish Congress, leaders like Rabbi Joachim Prinz actively participated in key civil rights events, including the historic March on Washington in 1963.

[29] During the Progressive Era, Jewish reformers like Lillian Wald and Jane Addams were instrumental in establishing settlement houses and social welfare organizations aimed at addressing the socio-economic challenges faced by immigrants in urban centers.

[31][26] The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was established in 1909 in response to the widespread racial violence and discrimination against African Americans.

At its inception, the NAACP aimed to dismantle institutionalized racism and secure civil rights for African Americans through legal means.

[36] Jewish lawyers within the NAACP, such as Charles Houston (often referred to as the "man who killed Jim Crow")[37] and Jack Greenberg (who succeeded Thurgood Marshall as the head of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund) played critical roles in landmark cases like Brown v. Board of Education, which declared state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students to be unconstitutional.

[39] The Anti-Defamation League's involvement in the civil rights movement included partnerships, legal interventions, opposition to hate groups, and educational initiatives.

During the Civil Rights Movement, the ADL supported African American leaders and organizations, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

[45] The ADL also actively opposed segregationist organizations like the Ku Klux Klan, monitoring and exposing hate groups that promoted discrimination and violence against African Americans.

[46][42][47]Founded in 1918, the American Jewish Congress (AJC) was committed to promoting social justice and equality, and actively engaged in various civil rights initiatives.

[18] In 1958, King Jr. was invited by Levinson to speak to the AJC's Miami conference — one of the few anti-segregationist organizations to convene in the South — and highlighted the shared impact of racism and segregation upon Blacks and Jews alike.

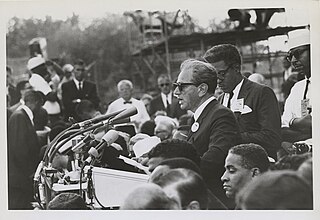

[3] Rabbi Joachim Prinz, who served as the AJC's president after Goldstein (1958–1966), emphasized the shared commitment to justice among diverse communities — most notably in his speech at the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963, delivered just before King's iconic "I Have a Dream" address.

[54] Jack Greenberg was a distinguished American attorney and civil rights champion known for his leadership at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF) from 1961 to 1984.

Greenberg contributed to several landmark cases, including the successful defense of James Meredith's right to attend the University of Mississippi in 1962,[57][38] and Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education (1969), which compelled the immediate desegregation of public schools.

Settling in Newark, a city with a significant minority community, Prinz spoke against discrimination from his pulpit, participated in protests across the U.S., and advocated against racial prejudice in various aspects of life.

[61]As president of the American Jewish Congress (AJC), Prinz sought to position the organization prominently in the civil rights movement.

[61][60] Historically, the Civil Rights Era-collaboration between African American and Jewish leaders has been portrayed as a significant and positive development, marking a critical alliance against racial segregation and discrimination in the United States.

[69] Political activist and philosopher Cornel West has argued that even during the Civil Rights Era there was not a time "free of tension and friction" between the two communities.

"[7] Hannah Labovitz argued against the romanticization of the era, claiming it was not "a story about white Jews intervening to save the day after experiencing their own challenges, but rather one damaged community doing what it could to help another.

"[6] Historian Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz argued that only a few hundred non-Southern Jews took part in activism in the South, that both sides often failed to understand each other's point of view, and that the relationship was "frequently out of touch".

[70] Political scientist Andrew Hacker pointed to a disparity between Blacks' and Jews' perceptions of events, highlighting the differences in tone and focus between the two communities.

[71] As the Civil Rights Movement progressed, differences in approach, priorities, and perspectives arose between African American and Jewish leaders.

[7] Cheryl Greenberg attributes this to the perceived "deterioration of their schools and neighborhoods" and fears of violence due to civil rights protests.

[9] Lewis marched alongside Jewish community members and co-established the Atlanta Black-Jewish Coalition, emphasizing open dialogue and partnership.